Research between United States-based Princeton University and the University of Queensland (UQ) argues Australia can achieve its goal of a fully decarbonised domestic and export economy by 2060, while protecting natural capital and respecting indigenous land rights.

The key to success, the researchers say, is collaboration and integrated planning, where energy developers, state and local governments, landowners, and various interest groups such as conservationists and indigenous communities, work together to identity suitable land to host renewable energy infrastructure.

UQ Environmental Management Professor James Watson said in thinking about renewable energy planning, the study considers different biodiversity goals and protections for natural capital, which is critical when implementing projects.

“This is among the first works to put biodiversity and natural capital into the same picture as energy planning in Australia, which is a much-needed step in the right direction,” Watson said.

The Negotiating Risks to Natural Capital in Net-Zero Transitions research paper, published in the Nature Sustainability journal, says the biggest challenge is the need for approximately 110,000 square kilometres of land to host projects.

Princeton University Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment Research Scholar Andrew Pascale said the amount of land required for the energy transition is “massive”, and the speed at which infrastructure needs to be deployed, “unprecedented”.

“At the same time, we’ve shown here that not only can it be done, but that it can and should be done while incorporating the perspectives of many different stakeholders,” Pascale said.

The researchers propose a new approach to planning, moving beyond a ‘top down’ energy modelling that only considers resource quality and infrastructure proximity to existing transmission lines and substations.

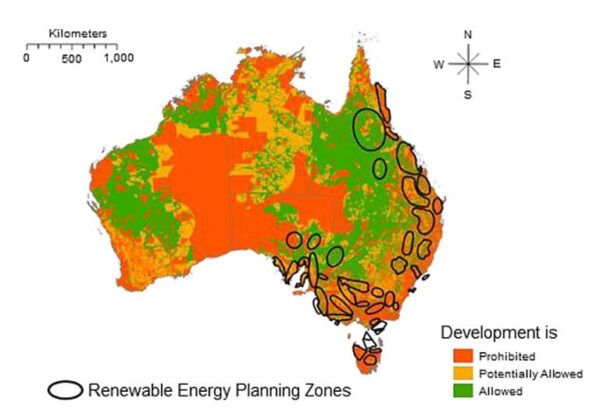

Image: Princeton University

Traffic light system

The model proposes a “traffic-light” system where land is green, if it’s the easiest to site and acceptable to diverse stakeholders, orange or yellow, if it’s potentially suitable but needs further stakeholder engagement, and red would be off limits to development for reasons such as being critical biodiversity areas.

The study also underscore uncertainties such as missing critical habitat data for many Australian species and how all species might respond to climate change, which would require regular model updates.

Watson said that such uncertainties should not prevent planners from using the best available data to take action on renewable energy development.

“We have to deal with the problem we are facing today, thinking about where endangered species are right now and focusing on keeping those habitats intact,” said Watson.

“We can take action while acknowledging we need better data, which is far preferable to simply forgetting or ignoring biodiversity.”

He added, the paper is a wake-up call.

“The take-home message is that we need a clean energy future, and that we need to plan for that future — and the large spatial footprint it will require — without defeating our other societal goals.”

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.