From the January edition of pv magazine

In early November 2018, the first electricity from the 220 MW Bungala solar project in South Australia began flowing into Australia’s National Electricity Market (NEM). The event was picked up by Paul McArdle, the managing director of Global-Roam, an advisory body serving NEM participants and equipment suppliers.

RenewEconomy, reporting on the event, noted that Bungala was vying to be one of the largest solar projects on Australia’s NEM, alongside the 250 MW Sunraysia project in New South Wales (NSW), the 313 MW Limondale in NSW, and stage two of the Kiamal solar project in Victoria (400MW). Bungala is rated at 275 MWdc in two 137.5 MWdc stages.

The project is owned by Enel Green Power and the Dutch Infrastructure Fund, the latter having recently rebranded DIF Energy Partners. The project was acquired by the joint venture in April 2017 and has a PPA with electric utility and retailer Origin Energy.

At the time of the acquisition, a DIF Australia spokesperson noted that it was “delighted” to pick up its second large-scale solar asset in the country.

“This investment represents an attractive, large-scale solar PV energy investment, underpinned by stable, long term contracted cash flows.”

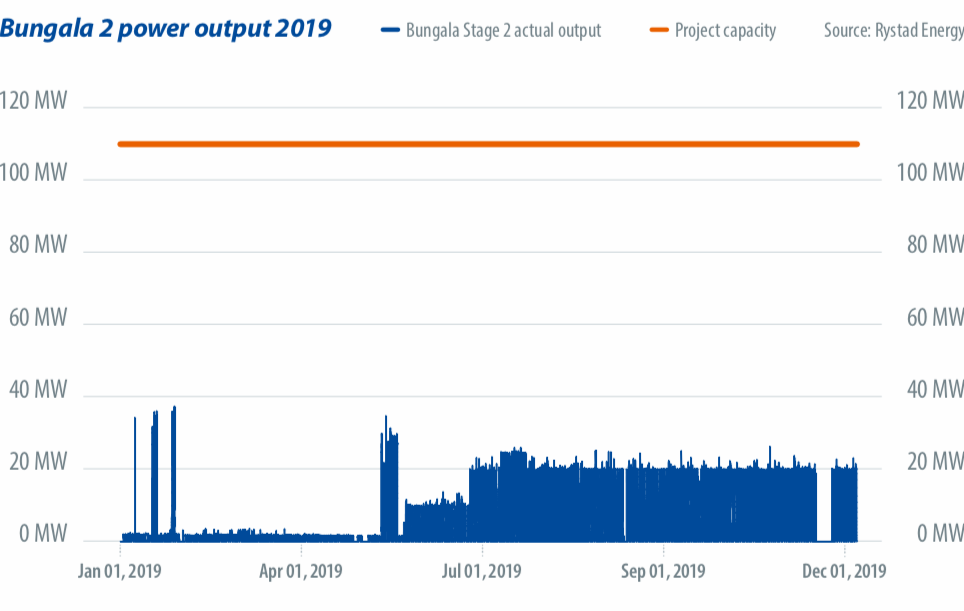

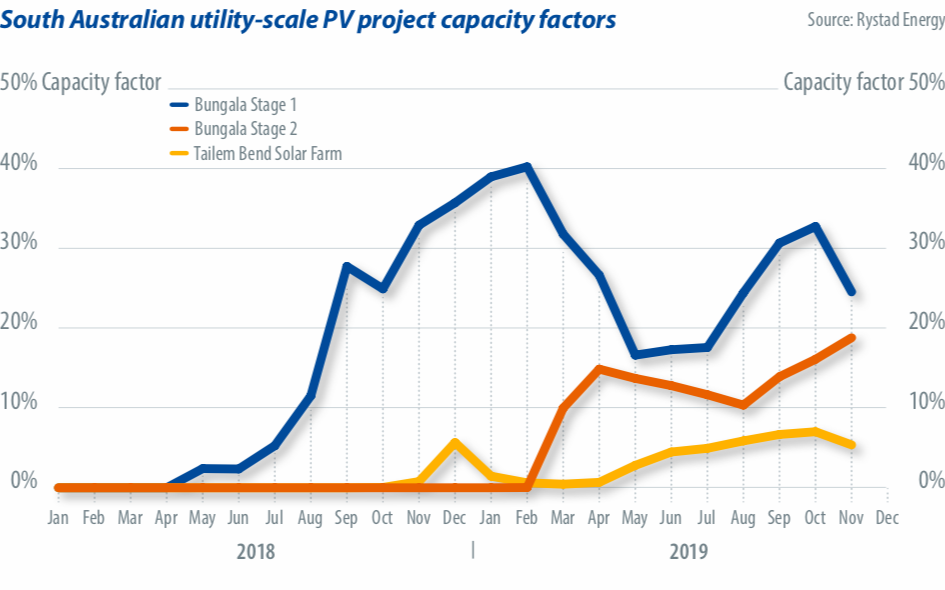

If only it were that simple. Since its initial electrification in late 2018, Bungala has not been able to ramp to anywhere near its full capacity (see chart below). Rystad Energy’s Dave Dixon has tracked the plant’s inability to feed anywhere near its nameplate into the grid, noting that the problems lie in the commissioning process with grid operators and the market regulator, the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO). Rystad has identified a number of projects that are operating well below their planned capacity factors.

“Bungala 2 is stuck at hold point one due to harmonics issues,” said Dixon. “I believe they need to acquire and install a harmonic filter before they can proceed to the next phase of testing.”

For Bungala’s owners, this delay in achieving full generation has serious consequences. Not only are the revenues for the power generated being lost, but also the project’s Large Scale Renewable Energy Certificates (LRECs), which are also contracted to Origin under the PPA.

Obtaining GPS

The sticking point with Bungala relates to the process of PV power plants obtaining Generator Performance Standards (GPS). The process involves working with the network operator, or Network Service Provider (NSP), and AEMO. The project must gradually ramp up to a number of hold points, or a proportion of maximum power output. At each hold point, the solar park must convince the NSP and AEMO that the power plant will not be deleterious to grid operation, which includes factors such as grid frequency and harmonics. The hold point testing process is referred to as R2 testing.

“The rules and requirements around GPS changed in February this year,” explains Lilian Patterson, a policy expert at Australia’s Clean Energy Council (CEC). This follows on from the application of a “Do No Harm” principle to new generation assets on the NEM, which was put in place in July 2018 and places the onus on generators, like solar projects, to be responsible for ensuring that their operation does not negatively affect grid reliability and system strength. One particular challenge facing solar arrays like Bungala, which face long periods in which they cannot generate at full capacity, is timing. Solar irradiation varies significantly between summer and winter, even in sunny Australia. A solar park may simply be unable to reach higher hold points in winter and have to wait for a change of system to recommence testing at a higher hold point.

“As much as they can plan, some projects just can’t get to a specific point when they intended to and now have to wait for summer,” says the CEC’s Patterson.

Potential resolution

Severe curtailment of PV project output is not an uncommon feature of many solar marketplaces that have expanded rapidly. This has clearly been exacerbated in Australia by rule changes that have occurred once project development was well underway. An additional challenge is that different NSPs in the various Australian states may take divergent approaches, meaning that learnings in one state may not be immediately transferable to another.

“The delays have been horrendous and it seems almost everyone is affected,” says Tristan Edis, an analyst with Green Energy Markets. Perhaps most worryingly, five large-scale projects in western Victoria and neighboring NSW have been curtailed to 50% of their rated output by AEMO after having obtained GPS. With this occurring during a period of record high temperatures and the resulting peak electricity demand, there are consequences not only for project owners, but also for Australian homes and businesses.

The CEC says it is working to find a resolution to the GPS issue while NSPs and AEMO have shown a willingness to find a resolution. And the responsibility for grid operation may not always lie solely with the solar farm. Such recognition could avoid millions of losses for the installation of devices such as synchronous condensers and harmonic filters alongside a solar project, which would be welcomed by project developers, EPCs and investors.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

2 comments

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.