From pv magazine 10/2021

Indonesian energy company Pembangkitan Jawa Bali’s (PJB) efforts, dating all the way back to 2017, have finally met with success, thanks to a long-term power purchase agreement that brings the 145 MW Cirata floating PV plant to financial close. PJB’s subsidiary, PJBI, has partnered with Abu Dhabi-based Masdar, a renewable energy group, to form a joint venture called Pembangkitan Jawa Bali Masdar Solar Energy (PMSE). Masdar holds a 49% stake in the new entity, while PJBI holds the other 51%.

Masdar, which has a total of 11 GW of renewable energy projects throughout the world, has global experience in negotiating engineering, procurement and construction (EPC) contracts. “We have brought the design of the financing for commercial banks into the Cirata project,” explains Przermek Lupa, president director of Masdar, on the expertise that Abu Dhabi brings.

Lupa acknowledges that the biggest challenge to the project is to establish an industrial local “ecosystem” to create PV technology with sufficient local content contributions.

Wirawan, the operations director of PJBI, agrees that in terms of the pioneering project, technology and engineering issues will be a challenge, particularly anchoring and mooring at depths of 80 meters in the Cirata Dam.

“The EPC that already has been appointed by PMSE, needed to comply with a rule of 40% local content as regulated by the Ministry of Industry, which has the development of a national PV industry on its agenda,” Wirawan explains.

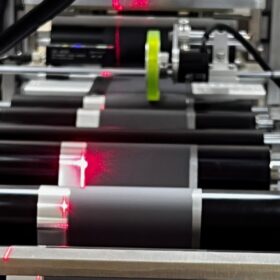

The project is said to use state-of-the art PV modules to suit the specific environment in Cirata. In an explanatory video, Dimas Kaharudin, the operations director of PSME, elaborated on the option of using dual-glass module technology “to minimise water ingress. Each module has a maximum efficiency of 21.61%, with a capacity of up to 560 Wp.”

Javanese regulations

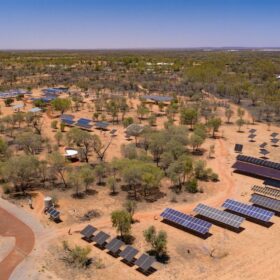

The Cirata water reservoir is located in Central Java. Even though the reservoir is owned by PJB, the transmission of electricity to substations still requires a land acquisition permit. The location was chosen due to its long history with the Cirata hydropower plant (established in the 1980s), which made the licensing process easier. Added benefits include the co-location of hydro with floating PV for improved intermittency, and the use of an existing substation 5 km from the planned floating PV (FPV) site.

Interestingly, the use of FPV was not yet regulated when the project was first planned. “We needed to propose a revision to the Ministry of Public Works and Housing Regulation 6/2020, to add the term of allowing ‘floating PV to generate energy in water bodies,’ because what the regulation allowed was just limited to tourism, water sports, and fishing activities,” adds Wirawan.

The effort paid off when the ministry allowed 5% of the water’s surface to be utilised for FPV. However, the project still had to fulfil the dam safety regulations and provide an environmental impact report, even though a growing global consensus shows FPV plants are environmentally sound.

Ups and downs

The project has seen some ups and downs, but the agreed tariff of $0.058179/kWh is significantly cheaper than the national basic cost of electricity supply in Indonesia, currently $0.786/kWh. The project has closed a long-term power purchase agreement on a two-year commercial operation date (COD) with a 14-year repayment period.

“It is a quite competitive tariff and a strong piece of evidence that renewable energy has become more affordable in Indonesia. Masdar and its partners have invested in the project to make it viable and economically sound. We believe that this tariff is just the beginning, and that the cost of renewable energy is going to drop and continue to drop in Indonesia,” says Lupa.

“To be honest, we were challenged by PLN as the offtaker on this tariff cap. We need to be wise on implementing the right technology, plan a viable financial scheme, and make sure the project does not have any event of default,” adds Wirawan on the tariff’s significance. Any potential fault that occurs on the project could discourage lenders from financing the project.

“The other challenge is to structure this project, because the participation of the state-owned enterprise PJBI holds 51% shares of the project. This creates issues related to the World Bank’s policy on negative pledge. We needed an innovative way to structure the project and offer security to the lenders,” explains Lupa.

On the other hand, the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, through its Regulation 48/2017, does not allow the transfer of shares to another party in the construction period before the COD, which could be risky for lenders in case of a default.

“We finally decided to create two layer companies after PJBI to give more security to the lenders, which was not a common practice before, but an exception for the Cirata FPV Project due to its status as a strategic national project,” Wirawan explains. At the financial close in August 2021, the project successfully attracted three lenders: Standard Chartered Bank, Sumimoto Matsui Banking Corp., and Société Générale.

The project has an estimated completion date at the end of 2022, and will be the first and largest FPV power plant in Indonesia. With Cirata serving as a model, Indonesians can now harvest solar energy with FPV modules from 5% of its dam and reservoir water surfaces.

Given this precedent, a senior energy ministry official, Dadan Kusdiana, was recently quoted by Reuters as estimating that Indonesia could potentially generate an additional 28 GW of solar energy from FPV situated on 375 suitable lakes and reservoirs spread throughout the country.

Author: Sorta Caroline

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.