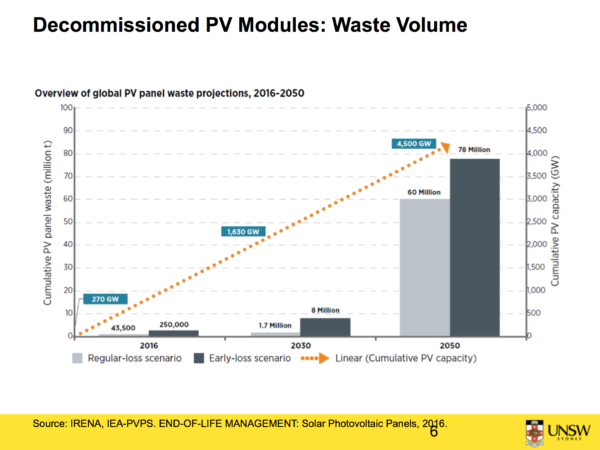

Governments and PV manufacturers around the world are applying themselves to solutions for processing the anticipated 78 million tonnes or so of end-of-life silicon PV modules that will enter the global waste stream by 2050.

In April, a group of four researchers from UNSW published an assessment of the approaches developed to date, economic barriers to their widespread implementation, and the potential for material recovery and profit from a future PV-upcycling industry. The study, already widely hailed, puts Australia at the forefront of understanding the economic drivers and possibilities ahead.

By 2050, the world will have an estimated 4,500 gigawatts of solar installed, according to data from the International Technology Roadmap for Photovoltaic (ITRP) and, “A lot of countries have caught on to module recycling,” says CheeMun Chong, Professor at the School of Photovoltaic and Renewable Energy Engineering, at UNSW, and a co-author of the study, A techno-economic review of silicon photovoltaic module recycling.

Early and eager adopters of PV, such as China, the EU, Japan, the US and South Korea have variously comprehensive national programs for dealing with PV waste.

Chong says, “There’s a lot of research work happening,” driven by some overseas government requiring manufacturers to take responsibility for stewardship of the modules over their 15- to 30-year lifecycle — and pay a deposit on each panel sold, to cover their potential default. As a result, the past 10 years have seen more than 100 patents registered on recycling technologies.

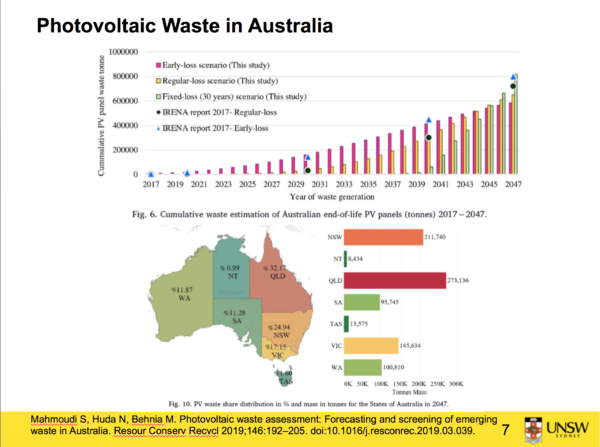

To date, Australia has no plan in place to encourage manufacturer responsibility, collects no levy against their default, and only Victoria is set to ban used solar panels, batteries and inverters, along with other electronic waste, from landfill — legislation that comes into force on July 1 this year.

That said, Sustainability Victoria (SV) is conducting a research project, with Equilibrium sustainability consultants and Ernst & Young, to understand the end-of-life management approaches for PV systems. “We’re ahead of a significant waste issue,” Michael Dudley, Strategic Lead for product stewardship with SV told pv magazine. “Panels are still largely in situ, but in the next three to five years we’ll start to see significant volumes enter the waste stream, which would then trigger private investment and capacity for reprocessing.”

Dudley says Sustainability Victoria advocates implementing an Australia-wide requirement for handling end-of-life solar systems. He says, “Regulation provides confidence to the private sector to invest in this area. Without a system of shared responsibility, the proposition for recycling isn’t as clear.”

UNSW’s study found that without regulation, sending end-of-life solar panels to landfill is the most economical way to dispose of them, but there’s a high risk that toxic elements, such as lead, cadmium and telluride, used in many panels will leach into soil and groundwater.

And then there’s the sheer volume of materials — glass, aluminium, silver, copper and silicon — that could be reused if they could economically be recovered.

In Australia, where photovoltaic waste is projected to reach 800,000 tonnes in 2047, the economic value of the materials contained in that number of panels was this year calculated by a group of Macquarie University researchers to be in the vicinity of US$1.25 billion.

Globally, says Chong, if we could recycle all the materials from the 78 million tonnes of end-of-life panels generated by 2050, “We’re talking US$15 billion in material recovery alone.” That’s not taking into consideration the jobs generated by such a major recycling industry, or the environmental benefits of keeping the recovered materials out of landfill and in the circular economy.

“Putting costs aside,” says Chong, “all the materials we’d get back from 80 million tonnes of waste would translate to 2 billion new solar panels — or, in today’s technology, 630 GW of generation.”

Of course, cost is the crux of the matter, and that’s where the work of the UNSW team, led by PhD student Rong Deng becomes instructive and vital. The calculations involved more than 100 variables. In simple terms, it compared the costs and material recovery values of four kinds of methods of dealing with end-of-life solar panels: landfill; glass recycling; mechanical recycling (separation of materials); and thermal recycling (using controlled heat to delaminate and separate materials).

The upshot of the study was that “under certain circumstances, recycling solar panels can be profitable”, says Chong, “which is very exciting”.

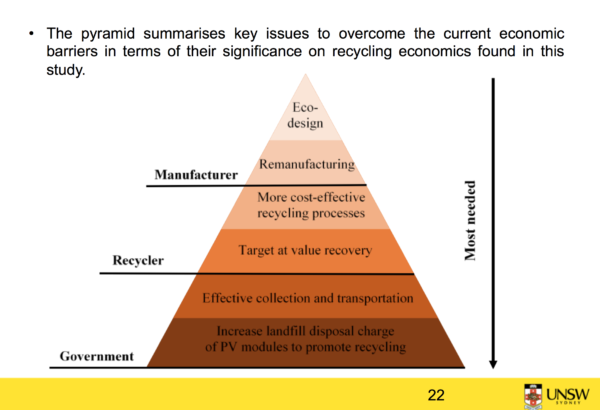

Conditions identified for improving the viability of recycling include: regulations that discourage landfill as an option; simplified and improved recycling processes focused on increasing rates of materials recovery — particularly of silver and intact silicon wafers; potential changes to module design that better facilitate recycling; a co-ordinated approach by governments and recyclers to building the recycling network; and consideration by manufacturers of how to incorporate second-life materials into their production lines.

Chong is seeking funding for a next phase of investigation, and has begun discussions with Australia’s Advanced Manufacturing Growth Centre, because he says, “We’re at a point where we believe it’s time to scale up.

“We’ve identified the barriers, identified the opportunity, and we’re collaborating with groups outside the university that are advanced in coming up with solutions to the technical aspects of recycling.”

His goal is to help accelerate those solutions, and establish the IP for world’s-best PV upcycling practices that Australia can implement and export to global markets.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

Interesting study.

Why not incorporate

1. 1st & foremost Architectural &or Building STANDARDS into PV Modular DESIGN ;

2. Recycle end of life Solar Panels as

2.1 privacy WINDOWS ;

2.2 Skylight DIFUSERS ;

etc

The most awkward ” Renewables ” waste inconvenience will be WIND TURBINES as 21C STOBIE POLES !

Cheers Jeff M. Weeks

CPA SA Fin Researcher Analyst

WMaxJeff@gmail.com