The Bridgestone World Solar Challenge (BWSC) has kicked off this week gathering teams of students from around the world looking to push the boundaries of technological innovation and travel 3,000km across a challenging landscape from Darwin to Adelaide in solar-powered vehicles. This year’s event featured 53 entrants from 23 countries, including seven from Australia.

One of Australia’s big hopes, the UNSW Sunswift solar car team is readying to hit the road on Sunday following a series of mechanical and electrical improvements to its four-seater VIolet. While it was forced to withdraw from the 2017 event due to a rear suspension failure, this year the Sunswift team is hoping to take line honors in Adelaide.

The team has practically re-built VIolet since the 2017 race, and driven her over 4000km from Perth to Sydney to set a new world record in efficiency last year. To achieve this, the team had to keep the car’s energy consumption to under 5.5kWh/100km. Actual energy consumption throughout the journey was an average of 3.25kWh/100km, which is about 17 times less than an average Australian car. The Sunswift team managed to complete the journey traveling an average of 600km a day and completed the journey in just six days and two days ahead of schedule.

According to Matt Holohan, the Sunswift project manager, who drove VIolet when it set the Guinness World Record last year, the team has made big improvements to the car’s efficiency. Since the last BWSC, Sunswift has replaced the front and rear axles to reduce the rolling drag, and reduced the energy consumption of the cruise control system. In addition to a fresh paint job and design touches, the team has also enlarged the battery pack to account for the new rules around charging.

New and old challenges

In a push from organisers to make the event more realistic this year, a new rule restricts competitors to just two charging opportunities – at Tennant Creek and Coober Pedy, while in previous years competitors were able to charge whenever they wanted to. This means the teams will have to travel about 1000km on a single charge.

“This will be a massive challenge,” says Holohan. “We will have to manage our speed very carefully and monitor our power consumption more closely than ever before. And pray for good weather.”

In comparison to previous generations of Sunswift vehicles, VIolet is the first four-seat, four-door vehicle. It is designed as a family vehicle with an eye on the team’s goal to build a car that can meet the requirements for road registration in Australia. It features a five-square-metre solar array consisting of 318 SunPower monocrystalline silicon cells with an approximate efficiency of 22% and a modular lithium-ion battery. It has a maximum speed of 140 km/h.

On the road, VIolet handles very differently to a normal car. Numerous factors make navigation difficult, including road traffic, uneven terrain, potholes, dead animals as well as wind gusts, which according to Holohan, are probably the most difficult to tackle. “You might have a strong side wind with you for a long stretch, which can make it challenging to drive in a straight line,” he says. “You can’t see a wind gust so when driving you always need to keep the possibility in mind to stay safe.”

With the main priority to keep the driver safe, a lead car in front of VIolet is constantly monitoring the road and telling the driver what’s coming up. During this year’s race, there will be two people driving the vehicle – 19 year old, first-year engineering student, Jed Cruickshank and 21 year old, third-year electrical engineering student, Reuben Hackett (the two will alternate in two-hourly shifts).

“We are really well prepared and I think VIolet would have to be one of the most tried and tested cars in the race. I’m feeling confident we can take the chequered flag in Adelaide on Friday,” Hackett says. As per the new charging rules, he says the team will have to monitor its speed and power consumption more carefully than ever before, to make sure it does not run out of power short of the designated charging stations.

“In terms of energy management, especially if it’s cloudy – or worse, if it rains – we’ll either have to try to beat the clouds or go slower to conserve energy,” he adds.

Interestingly, Reuben’s grandfather, Alex Hromas, helped design one of the very first solar electric cars to drive the route from Darwin to Adelaide in the first BWSC in 1987. “I’d just designed a solar electric power system for a consulting job, so my friend asked me to help build a car for this new race,” Hromas says. “All the cars back then were single-person race cars; they were very lightweight. The roads were a bit hairy too – there was a single strip of bitumen and a lot of road trains.”

“The organisers ran a stability test before the race by driving a B-double [semi-trailer] at us at 140km/h and if we didn’t flip over in the wind buffet, we were good to go,” he adds. In the last piece of advice ahead of the race, Hromas encouraged his grandson to enjoy every minute of the Challenge.

This year, VIolet will be competing in the BWSC for the last time before the UNSW Sunswift team begins designing their next solar vehicle.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

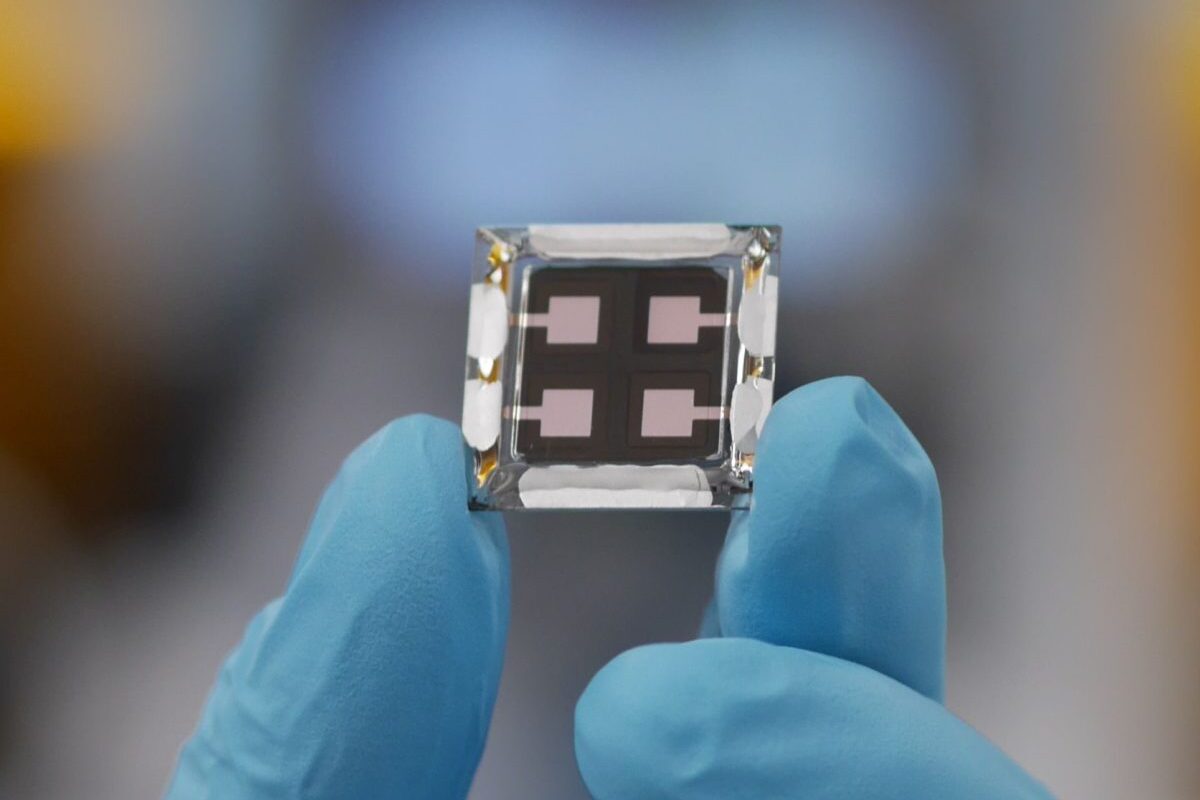

This would be an excellent platform to try out a tandem solar PV cell technology. Perhaps, standard high efficiency mono-crystalline solar cells with a spray on coating of perovskites to pump up cell efficiency to 35% or more solar harvest. Imagine getting to the point of driving the “challenge” with an initial charge and no need to recharge along the way. If the team can get the drive technology power requirements to the 2kWh/100 kilometer point, a tandem cell would probably do the “trick”.