pv magazine: Prof. Overland, there is growing interest in the long-distance transport of energy in the form of electricity or hydrogen. However, large-scale infrastructure and clean fuel shipping will inevitably raise geopolitical concerns. Could this impact be similar to that associated with the long-distance transport of fossil fuels?

There may be some similarities, but I think there will also always be differences. Everybody has some renewable energy, so there is unlikely to be the same complete dependence on long-distance imports as many countries have had for fossil fuels. As it has been formulated elsewhere, renewable energy exporters will often be competing against their customers.

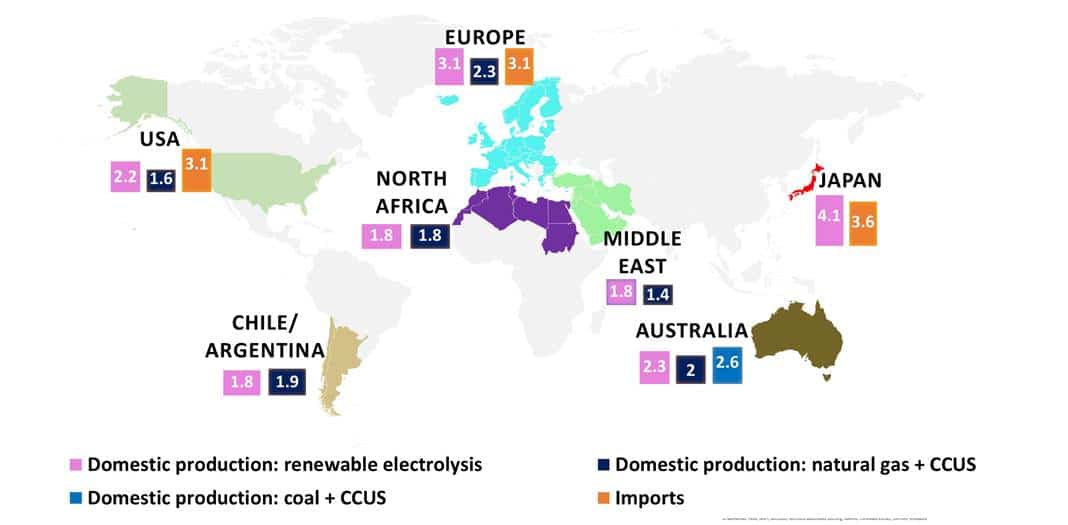

The importers will be buying their energy because it is a bit more convenient and cheaper than producing their own, but if the risks and nuisances become too great, they might as well produce their own. So the exporters will need to treat their customers very nicely and cautiously. International trade in hydrogen might be a bit like overseas trade in liquefied natural gas (LNG) and to some, but a lesser extent similar to trade in oil. However, whereas natural gas and oil are only located in high concentrations in a minority of countries, more countries have an abundance of renewable energy that could be used to generate hydrogen.

Thus, the producers in a global hydrogen economy would not have quite the same privileged position as the producers of oil and gas. It is also worth noting that the global markets for oil and natural gas are quite different, and whereas the former is basically fungible and can be moved anywhere in the world, the latter does not have a fully integrated world market yet.

Despite the growing trade in LNG, LNG trade relationships are sometimes referred to as “floating pipelines,” and there are frequently large differences between the price of LNG in different parts of the world. Hydrogen will likely be more like LNG than oil due to the small initial market and large up-front capital requirements in infrastructure.

pv magazine 05/2021

Could long-distance cables or pipelines be comparable to the controversial Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline that is being built to bring Russian gas to Europe? Could electricity or hydrogen transport raise the same international tensions as gas pipelines?

NordStream 2 is controversial for several specific reasons. Because it increases EU dependency on Russia, because it is a tool for Russia to reduce its dependency on and thus gain power over Ukraine. Because Germany and German and other natural gas companies are pushing hard for it, although many other Europeans do not see it as being in the EU’s interest. And above all, because it locks in infrastructure for future expanded imports of fossil fuels.

Taking into consideration all of these points, the international trade in renewable energy is very unlikely to be similar to NordStream 2. However, in principle and at a general structural level, trade in renewable energy could be similar to gas pipelines, especially if the energy is moved in the form of electricity via subsea cables.

A 14 GW solar project coupled to 33 GWh of storage is currently being planned in Australia’s Northern Territory. The developer hopes to sell the generated energy to Singapore via a 4,500-km, high-voltage direct-current transmission network, including a 750-km overhead transmission line from a solar project in Darwin and a 3,800-km submarine cable from Darwin to Singapore, via Indonesia. What are the potential geopolitical consequences for Australia and the broader region, assuming that the project actually gets built?

I don’t think this project is realistic. The cables are incredibly long and expensive and they would traverse the so-called Pacific Ring of Fire, a part of our planet that is particularly prone to volcano eruptions and earthquakes. If Singapore really needs to buy renewable energy from Australia, it would likely make more sense to transport it as hydrogen. This would give both the Singaporeans and the Australians more flexibility, in case there are any disruptions or changes of plans.

Singapore could also work more on other options. Despite lack of space for renewable energy installations, the Singaporeans could do a lot more to develop their own energy system, by raising energy efficiency and facilitating accelerated rooftop and floating solar power development. They could also work harder to build trust and source electricity from neighbouring countries and then have a smaller portion of expensive long-distance hydrogen with an option to ramp up in case of a need. This long-distance element could be partly from Australia and partly from other sources for further risk mitigation.

Another 10 GW wind-solar complex coupled with 20 GWh of storage is currently being developed in Morocco. The electricity produced by the huge plant could potentially be exported to the United Kingdom via a 1.8 GW submarine cable that would cross the territorial waters of Morocco, Spain, Portugal and France. Assuming that this ambitious project is completed, would this mean the success of the Desertec dream? What kind of geopolitical impact could this have on North Africa and Europe?

The Morocco-U.K. project is slightly different from Desertec – and perhaps not quite as rational, since the U.K. is not on the Mediterranean – but the principle is similar. I think something along the lines of Desertec is inevitably going to be realised sooner or later, and probably sooner rather than later. North Africa has incredibly rich renewable sources, both in terms of sunshine and wind. Equally importantly, North Africa has huge amounts of available suitable space for solar and wind power and very large markets nearby in Europe. In that regard, the starting point is much better than for the Australia-Singapore project.

Where could the most strategic links for power and hydrogen transmission be built? Are there specific regions that would benefit more from such infrastructure?

I think the North Africa-Europe axis is the most promising one. Central and Western Europe have very little free space due to population density, farming and sprawling infrastructure. They have very high energy consumption due to wealth and cold climate. They have purchasing power – they do not want to become overly dependency on eastern neighbours.

Europe is also the global leader in climate policy and renewable energy installation and needs more energy sources and connections to stabilise its own supply of intermittent renewable energy. As explained, above, North Africa has correspondingly good conditions for renewable energy developments, and the distance to Europe is not that great. Another possible axis might be Mexico-USA, but the USA has quite a lot of space and resources of its own and is thus different from Europe. Australia-Asia as discussed above might also be an option, but Australia is far away, especially from the large markets like China, Japan, and South Korea. Mongolia/Russia/Central Asia-China/Korea/Japan is another possible axis. I don’t think any of these axes have the same potential as North Africa-Europe, but they may still be developed later on.

Could hydrogen pipelines be a better option than electric cables? Hydrogen could also eventually be transported via existing gas pipelines, provided that they are suitable for the transport of the clean fuel.

There are different views among experts, but most seem to be tilting toward the view that natural gas pipelines can be repurposed for hydrogen relatively easily. So, yes, that could give hydrogen an advantage. However, hydrogen also has a disadvantage in that its production is not very efficient.

It also seems unlikely that hydrogen will ever play a major role in person vehicles, as batteries are advancing fast, and even for heavier transport, the question is open. I think the really promising initial niches for hydrogen are in handling intermittent renewable energy and in certain industrial processes. Where and whether it will grow from there and whether it can compete with other options like batteries and interconnections is hard to say.

What kind of alliances might arise around these big projects? What are the biggest potential obstacles?

Since I see the North Africa-Europe axis as most promising, I think that is also where there is the greatest scope for the development of international relationships based on energy projects. Such developments will probably create some losers, but I think they will be so indirect and far down the line that it is difficult to see what they could do to oppose such projects. Perhaps Russian engagement in Libya could be seen in such a perspective, but I don’t think the Russians are thinking along those lines at all at the moment.

Is there any chance we might see a hyper-connected world with an increasing number of cables and pipelines, if more large-scale projects are built to bring down costs?

I think we will see a lot of integration within countries, within regions and between regions. For starters, north and south Germany need better connections. But I don’t think there is going to be a need to connect the whole world. For example, connecting the Americas to the rest of the world would be expensive and introduce new risks that would outweigh the advantages. The Americas are big enough on their own to handle the intermittency.

Is it possible that energy, including both renewable electricity and hydrogen, will be consumed mostly on site or close to production, rather than transported to other distant locations? What conditions will be needed to make this happen?

This is a very interesting question. Embedded renewable energy is a new area I am working on. If we look back at the fossil fuel past, we can see that such hopes and promises were often not realised. One of the main purposes of OPEC was to use oil and gas resources to promote industrialisation in the OPEC countries. But little ever came of it, despite some exceptions like Qatalum – the world’s largest aluminium producer, based in Qatar and using Qatari natural gas.

In addition, renewable energy resources are more evenly distributed in the world than fossil fuel resources. Although some countries have a lot of sunshine or wind and space, almost all countries have some and few are as disproportionately resource-rich as the Qataris are in terms of gas. I think there are still good prospects for renewables-based industrialisation, but it will require a very proactive and competent approach on the part of states rich in renewable energy resources.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.