Sweetman Renewables Limited, born of the century old Sweetman’s Timber sawmill in northern New South Wales, has entered into a joint venture with Singaporean company CAC-H₂ to produce hydrogen by gasifying woodchips.

The $15 million deal will see CAC-H₂ own 80% of the Hunter Valley-based operation, while Sweetman will own 20%, responsible for providing the wood feedstock, as well as EPC engineering.

The companies are branding the enterprise Australia’s “largest green bio-hydrogen production eco-hub,” though many experts have queried the technical classification of wood as “renewable” and the energy generated by burning it as “net zero”. Such assertions rely on questionable carbon accounting, not the mention encouraging an already contentious forestry industry.

The Hunter Valley One deal

The multi-million dollar facility, named Hunter Valley One, is set to be constructed on a 30-acre site adjacent to the Sweetman’s Millfield timber mill in the Hunter Valley.

The companies believe construction should commence soon, initially saying planning applications had already been approved. Sweetman’s chairman John Halkett later clarified to pv magazine Australia that approvals related to the supply of feedstock, that is green sawmill residues, are covered by existing contractual log supply agreements with the NSW government via the Forestry Corporation of NSW.

However, the siting of the Hunter Valley One syngas facility, he said, is still under consideration and subject to further engineering and other inputs. All prospective sites are existing industrial zones and if any development application (DA) modifications are needed, they will be subject to further scoping and consideration by the relevant local government authority if necessary.

Proposal details

Under the proposed deal, CAC-H₂ will bring its gasification technology which converts woodchips into 99.9% pure hydrogen via a proprietary process. “CAC-H₂ also brings Off-take Agreements for 100% of Sweetman Hydrogen and Biochar production.” This wording is slightly confusing, but it seems along with Sweetman Renewables, the company has also registered Sweetman Hydrogen – though it isn’t clear whether that statement refers to the subsidiary Sweetman Hydrogen Pty Ltd, or just simply the hydrogen produced by Sweetman Renewables.

Either way, Sweetman is set to provide the facility 30,000 tonnes of wood biomass per annum, which will be converted into woodchips and gasified to produce hydrogen.

“We initially planned to start with just two production lines but due to large demand from both Japan and Korea, we envisage to quickly scale up the Sweetman operation to multiple lines producing Hydrogen and Biochar for export markets via a new facility at the Newcastle Port,” Arman Massoumi, Director of CAC-H₂ Group, said in the statement.

“Over the next 2 years our JV will establish new Hydrogen Hubs in every state in Australia. Sweetman has already obtained expressions of interest to establish another Hydrogen hub at Newcastle Port and in additional hubs in Queensland and Victoria,” Glenn Davies, CEO of CAC-H₂ added.

Can hydrogen made by burning wood really be considered green?

Wood, or biomass as it’s referred to by the industry, is defined as a renewable energy source both in Australia and abroad. Even though, like coal, it emits significant amounts of carbon when burned, it is classed technically as “net zero”.

In a perfect world, burning and regrowing trees is a closed carbon loop – but our world is far from perfect and scientists are increasingly arguing biomass industries are destroying trees, our only proven carbon sequestering technology, only to dump carbon dioxide into the atmosphere amid an already out of control climate crisis.

Furthermore, the piece of carbon accounting that has deemed wood-burning “net zero” pays little attention to time. When exactly carbon parity is reached is hotly contested.

Earlier this year, more than 500 scientists signed an open letter to world leaders calling on them to “stop treating the burning of biomass as carbon neutral”. Others have attempted to go through the court system to revoke the status, as was done in the European Court of Justice in 2019, and last year in South Korea.

Biomass in Australia

Unlike other countries, Australia hasn’t historically relied on biomass for energy, and therefore has avoided some of the problems which have plagued Europe and the United States, where most of the woodchips are sourced.

Nonetheless, with our country’s pipeline of hydrogen bulging, projects relying on biomass are increasingly popping up.

For instance, Verdant Earth Technologies recently bought the mothballed Redbank Power Station in the Hunter region and plans to recommission the 151 MW station, now called Verdant Power Station, to run purely on biomass – sourced by Sweetman as well. Verdant also has hydrogen ambitions which it’s pursuing in the Northern Territory and elsewhere.

Likewise, Patriot Hydrogen is putting biomass at the centre of its hydrogen producing plans, though at a much smaller scale. Its P2H units, as they’re named, are essentially modular, hydrogen producing kits which run on biomass, with the company boasting they can be powered up anywhere, anytime.

Biomass is attractive to the burgeoning hydrogen industry because it provides predicable, base load power. Solar and wind, as abundant as they are here, remain at the whim of nature, giving companies that rely on burning a fuel source a more guaranteeable (though not zero-cost) input.

Cost of wood burning

Using biomass to make what will go on to be sold as renewable hydrogen, Suzanne Harter, a clean energy campaigner at the Australian Conservation Fund described to pv magazine Australia as “a bit like money laundering.”

Alongside the emissions, Harter says there are other costs to burning wood. The most obvious being the impacts it has on habitats and biodiversity. In a country still reeling from the 2020 Black Summer bushfires which burned 18.6 million hectares, nearly the size of England, and killed or displaced three billion animals, the continued logging of unburned forests in many states has been met with fierce community ire.

Victorian government is actually moving to ban the native hardwood industry while the Western Australia government also recently announced it would end logging of native forests from 2024. These stronger protections being introduced in other states is something Sweetman’s chairman John Halkett told pv magazine Australia earlier this year would give his company an even bigger share of the market.

Halkett also said then, in July, Sweetman’s plans was to double if not treble the log input for its sawmill, growing the facility’s production by the same amount, with Halkett describing demand for hardwood as “gangbusters”. These ambitions appear to already being coming to fruition with Monday’s announcement coming off the back of Sweetman’s partnership with Verdant Earth Technologies earlier this year.

Hunter Valley moves from coal to hydrogen

The Hunter region of NSW is set to become the home of one of the state’s first green hydrogen hubs, to which the NSW government has committed at least $70 million.

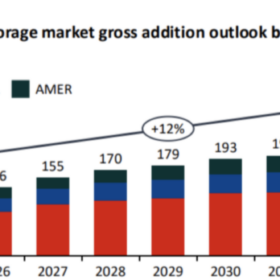

The market size for hydrogen in 2022 is projected to be around $155 billion, Sweetman noted in its statement. “By 2050, driven by a burgeoning global demand for zero-carbon emissions, the hydrogen market is expected to be valued at $12 trillion.”

While biomass is classified as net zero, it is certainly not zero carbon emissions. It remains to be seen whether hydrogen generated from that industry will come under the same scrutiny now being put on the government’s peddling of “clean hydrogen” which was recently discovered to have more emissions than if the fossil fuels used to produce it were burned directly.

–

This article was amended on September 14, 2021, to include comment from the chairman of Sweetman’s, John Halkett, clarifying specifically which aspects of the project had received approvals.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

This is nuts!

I would not be surprised if the prime minister of NSW and Barnaby of the Hunter were instrumental in biomass being classified as net zero.

Barnaby is not ‘of the Hunter’. He’s the member for New England – the next electorate north west. Tamworth and the Liverpool Plains.

Nonetheless, this is appalling. The Hunter despairs.

NO!!! Why do they was to destroy the only carbon capture storage that works. Let the trees continue to store carbon.