From: Cornwall Insight

This signals that energy transition is now well and truly on. However, targets are one thing; what about replacing capacity pending retirement in the short term? The NEM struggled during the most recent Q2, driven by high input prices and some outages, culminating in the unprecedented market suspension. With the imminent closure of Liddell looming, how well prepared are we?

Cornwall Insight Australia’s most recent Energy Market Perspective explored future commodity prices and how well we were able to compensate for the outages in Q2 2022.

In our report, NSW Q2 2023 was also identified as a hot spot for risk, with Liddell’s impending 1,500 MW of dispatchable capacity expected to be withdrawn by 1 April 2023. We previously discussed this topic almost two years ago when the closure was initially announced.

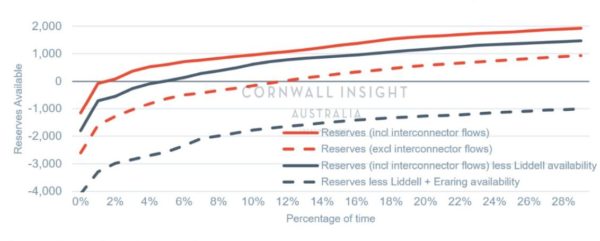

In this Chart of the Week, we take another look at reserve capacity for NSW based on this FY22 data and modelling the closure of Liddell, with a further hypothetical scenario should Eraring be unavailable.

Image: Cornwall Insight Australia

Concerns over Liddell’s reliability have been apparent for years and were a large reason for bringing forward its eventual closure, and the last year provided evidence for this. Liddell’s three remaining units (after the retirement of Unit 3) have operated at just 55% of its maximum bid availability of 1,260 MW post-April 2022.

Noting that although Liddell has a nameplate capacity of 1,500 MW, it has not submitted a full capacity bid since Unit 3 retired, preferring to operate at a comfortable baseload capacity of 350 MW per unit (83% of operating capacity) overnight and ~250-275 MW per unit (~60% of operating capacity) throughout the day in daytime pricing. Liddell was ramping to maximum during high-priced peaks occasionally.

Since the closure of Unit 3, the plant has had all three units operational 35% of the time, opting for a preferred two-unit operation 44% of the time. Despite these series of changes in operation techniques, Liddell still met ~8.3% of NSW’s total energy requirements this year (Liddell met at least 15% for NSW requirements until 2021).

Looking at reliability in peak periods since Unit 3 left the system and intervals where demand is > 10 GW (~13% of total), we see that the instances of NSW having a lack of reserves to meet peak demand are very limited. It is also important to note that NSW currently relies on other states to meet peak demand, needing to import at least 1,000 MW for 41.2% of the time, 500 MW for 77.8% of the time and 300 MW for 88% of the time. This illustrates a heavy reliance on importing energy during peak intervals to keep prices stable and energy flowing.

With reserves being ‘the ability of available supply to meet local NSW demand’, NSW had reserves of less than 1,000 MW available 10.5% of the time. Removing the availability of Liddell, NSW would have reserves of less than 1,000 MW for 16.8% of the time.

For the sake of discussion and beginning to think about what the retirement scenario for Eraring may look like, given its closure is just around the corner in 2025, the removal of both Eraring and Liddell would leave less than 1,000 MW of reserve for 98% of the time (on FY22 data), with no reserves at all for 73.3% of the time. These figures highlight the expansion needed to replace the looming ~4 GW gap, as seen in our chart.

With only 60 MW of available large-scale storage in the state (Queanbeyan and Wallgrove BESS’), and the pipeline still being murky with only ~450 MW expected by mid-year next year, the ability to replace generation in times of need remains questionable.

The trifecta of Darlington Point batteries has the potential to be online in Q2 next year, but this is just 150 MW. Another 50 MW will come in New England and Broken Hill each. Neoen’s 100 MW Capital battery will likely have a commission schedule in early 2023. The 100 MW Sunraysia Emporium battery has a planned 2023 date, but the news here has quieted down.

But all these are just enough to replace one unit of Liddell for a short time frame. While there are a number of other larger batteries, Tamworth and Armadale, together 300 MW in the works and expected to be operational in 2024 (but have yet to reach financial close) and a number of larger projects announced for operation in 2025, including Eraring 700 MW, Waratah 700 MW, Uranquinty 200 MW, and Liddell 700 MW.

Outside of storage, the Kurri Kurri gas-fired station likely won’t be commissioned until 2024. There is the potential for another ~400-500MW’s of solar to come online, but this does little for peak time demand. The news on wind is not much better, with no public news on the state’s potential commissioning schedules next year.

However, history suggests that it is extremely difficult to get projects operational on time, and this has been exacerbated by the current market and grid conditions, leaving a potential for a significant shortfall in reserves should any further coal units (like Eraring) trip in the short term, but also leaves the market on the edge in 2025 should any of the current pipeline of storage or gas projects become delayed.

The closures of Liddell and Eraring also both hold the potential to have a large impact on the cap market. The remaining thermal capacity should be able to meet the requirements in the short term, but forward fuel markets and another cold autumn and spring hold the potential to cause a disturbance.

Other recent announcements by Queensland and Victoria are positive that investment is expected to pick up. However, there is a stark difference between focusing on the long-term 2030 compared to next year as some storage projects face delays and increased costs.

The question going forward remains: are we prepared for another cold Q2 as we should be? Forward markets for energy and commodities remain high, and slip-ups by the coal fleet at the wrong time can have significant consequences. Furthermore, the reliance on interconnector flow in peak demand can create risk.

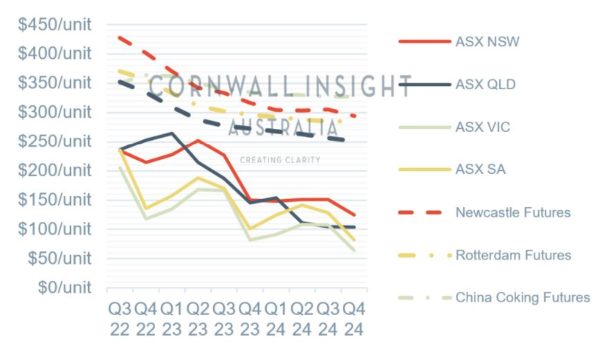

Future prices give us some indication of how we will fare next Q2 (refer Chart 2). High fuel costs are likely to remain over the short/medium term, as evident in future prices. This is signalled by ACCC LNG netback prices of ~$50-60/GJ over the short term. Even sustained high gas prices of $40/GJ (Victorian and NSW cap price) translates to short-run marginal costs for gas peakers of around $400-560/MWh to break even (assuming a common standard heat rate of 10-14 GJ/MWh).

Image: Cornwall Insight Australia; data – trading View, ASX

Maintaining sufficient available capacity, along with prices that are in the interest of both consumers and investors, will be one of the biggest challenges faced by the NEM as the retirement of ageing coal power plants accelerates and the generation mix features increased levels of renewable generation.

There is plenty of work to be done and investment to be made.

Author: William Curtis, energy market analysts, Cornwall Insight Australia

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those held by pv magazine.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.