From ISSUE 10 – 2022.

The economies of Southeast Asia are growing, along with their demand for energy. In its “Southeast Asia Energy Outlook 2022” the International Energy Agency (IEA) noted that after a brief disruption due to the Covid-19 pandemic, energy demand in the region is expected to continue to expand by approximately 3% a year, with economic growth at 5% annually, through to 2030.

These “tiger economies” remain reliant on fossil fuels for their energy supply. Three-quarters of the increase in energy demand anticipated by the IEA is forecast to be met by fossil fuels – resulting in a 35% increase in CO2 emissions. And carbon emissions are not the only problem. The IEA concludes that the reliance on conventional energy results in a “worsening in its energy trade balance as fossil fuel demand outpaces local production.”

There are, however, positive trends emerging in the region in terms of the adoption of renewable energy – with grid enhancement and regional interconnectivity set to play a crucial role in these developments. The IEA observes that 40% of the $108 billion (USD 70 billion) in energy investment that was made in Southeast Asia between 2006 and 2020 went towards “clean energy technologies – mostly solar, wind and grids.”

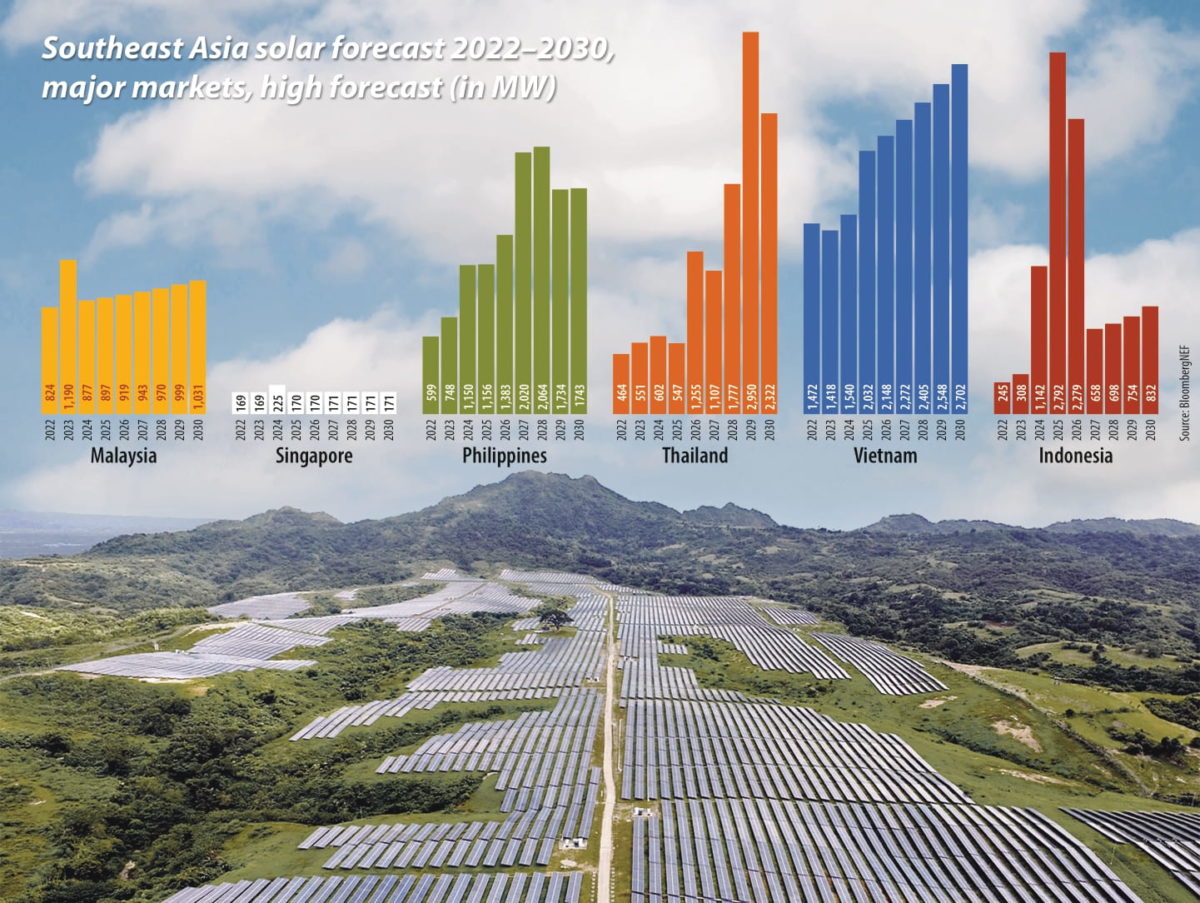

An accelerated expansion of solar uptake in Southeast Asia remains key, with most countries making pledges to reduce emissions. Corporate electricity consumers in the region are also seeking to decarbonise and boost ESG performance.

Interconnection plans

“Over the last five years we’ve definitely seen a lot of momentum in the region,” says Caroline Chua, who leads BloombergNEF’s Southeast Asia power and renewables research. “There has been a lot of interest from governments, financiers, developers, but on the ground, there are still challenges on the policy side, on the market development side, and even on the power market design aspect to unlock the industry further.”

Chua notes the differing challenges that the expansion of solar faces in each country, but says regional cooperation is underway to enhance grid interconnection and facilitate increased energy trading.

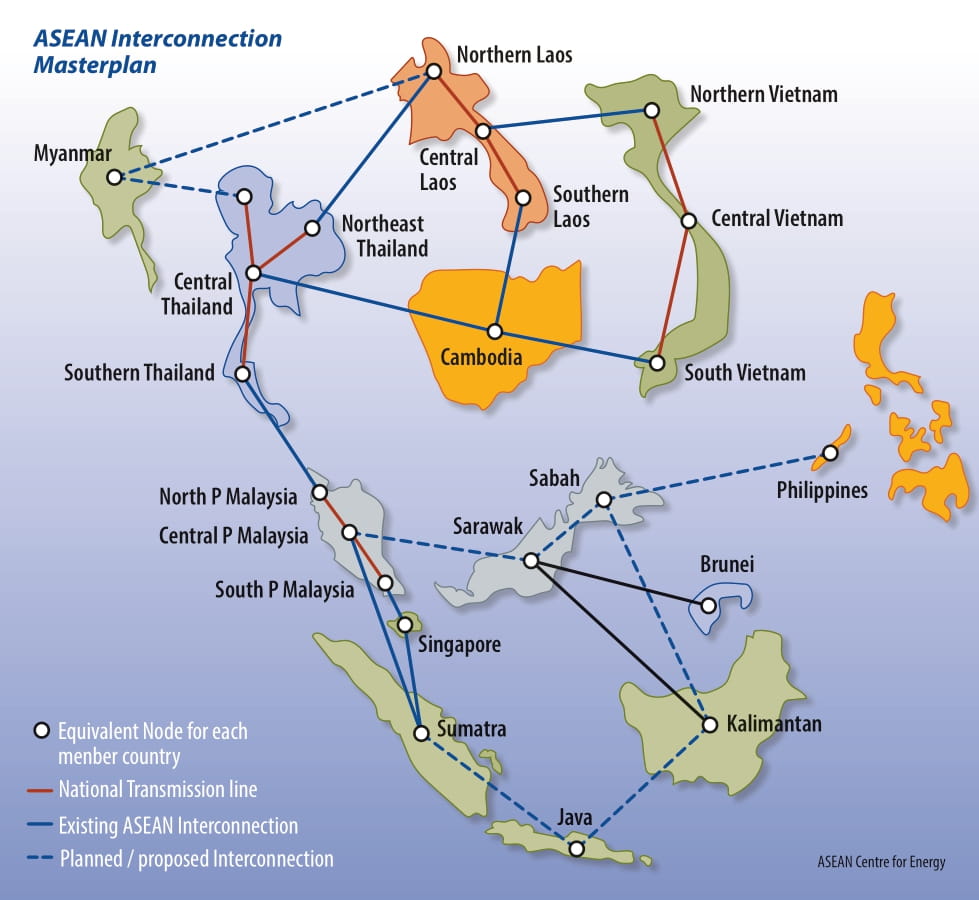

“There is the overarching discussion of the ASEAN power grid, which has been ongoing for several years,” continues Chua. “We are now starting to see some developments. They are connecting Laos, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore. It is not specifically for solar, but it could encourage more renewable development.”

Network needs are a common macro-trend in global energy markets. In September, advisory and risk management service provider DNV reported that 87% of the “energy leaders” it surveyed said “there is an urgent need for greater investment in the power grid.” Further, 76% of industry respondents reported that the availability of grid connection was a constraint in connecting renewable energy projects.

“We are now entering a paradigm shift and the industry must be prepared to work collaboratively to prepare our power systems for the future: to transition much faster, we have to integrate new technologies, and encourage grid investment through forward-thinking policies and regulatory frameworks,” said Ditlev Engel, CEO of Energy Systems at DNV, in a statement.

Interconnection, procurement

Enhanced interconnection between ASEAN countries has been pursued since 2016, with the joint goal of enhancing “energy security, accessibility, affordability and sustainability for all – according to the initiative’s stated aims.

The program, called the ASEAN Plan of Action for Energy Cooperation (APAEC), has reached phase two. The plan runs from 2021 to 2025 and includes a secondary goal of “accelerating energy transition and strengthening energy resilience through greater innovation and cooperation.” And there are clear benefits for the program for renewable uptake in the region.

Singapore remains an economic powerhouse in the Southeast Asian region, and a financial hub. The city state is reliant on gas imports for 95% of its electricity generation. And with gas prices high due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, electricity prices in Singapore are rising – in Q3 2022 the regulated residential price rose to around $0.33/kWh.

Singapore is adopting solar locally, and its Energy Market Authority (EMA) is pursuing a target of 1.5 GW of PV by 2025 and at least 2 GW by 2030. While meagre, these goals are dictated by the lack of land, the EMA notes, with PV to “likely constitute only about 3% of the country’s total electricity demand in 2030.”

To overcome this challenge, in October 2021 the EMA launched its first Request for Proposal for the import of part of an eventual 4 GW of “low carbon electricity imports into Singapore” by 2035. The first of these imports began back in July, with up to 100 MW of hydropower set to be imported from Laos via Thailand-Malaysia-Singapore interconnection – the LTMS-PIP.

The potential of solar exports to Singapore has garnered considerable interest, reports J.Y. Chew, the head of Asia renewables research at Rystad Energy, including in Indonesia. “Indonesia is in a very good position to take advantage of this,” says Chew. “It has lots of land on islands nearby to supply Singapore with renewable energy.” Solar projects established in Indonesia for export to its prosperous neighbour will likely be bolstered with energy storage, to maximise the number of hours each day solar could be exported via an expensive interconnector – supplying something approaching baseload power.

Rystad’s Chew adds that Vietnam may also look to export solar, which may, among other commercial aspects, ease curtailment issues in southern and central Vietnam.

An alternative to Indonesia and Vietnam lies further afield, in Australia. There, the hugely ambitious Sun Cable project has drawn the support of high-profile backers, billionaires Andrew “Twiggy” Forrest and Mike Cannon-Brookes, through their venture arms.

Yet while there is little doubt that Australia could generate low-cost solar in its far north for export to Singapore, the interconnection it would require is truly immense. “The Sun Cable project in Australia is just too long,” says Chew. “It’s a 4,000 km sub-sea cable through Indonesia. But surprisingly that project has been passing through a number of approval stages and, it somehow might pull through.”

The free flow of renewable energy is not a given everywhere, however. In October 2021, Malaysia made moves to halt the export of renewable electricity to Singapore – preferring instead to see its locally produced renewables used to meet national goals. Malaysian news agency Bernama reported that the country’s “Guide for Cross-Border Electricity Sales” was being reviewed to this aim, and that fees for transporting electricity across its wheeling charges for selling electricity to Singapore over a two-year trial period will be $0.035/kWh.

Vietnam’s cautionary tale

One of the outstanding solar markets in the region, and indeed globally, in recent years has been Vietnam. On the back of its national feed-in tariff program and relaxed foreign investment laws, Vietnam’s PV market exploded. The country installed just 200 MW of solar in 2018, rocketing to 5 GW in 2019 and 12 GW in 2020, according to BloombergNEF figures.

“The two solar FIT schemes drove two consecutive solar booms in the country,” says BloombergNEF’s Caroline Chua. “The supporting policies have ended and because of the current power market structure with one single off taker, and that there is no policy for them to purchase solar, there is now no way for developers to strike a power purchase agreement to sell their solar electricity to the grid.”

Chua notes that behind-the-meter projects are now the only ones moving forward, and it appears that the next round of Vietnam’s power development plans are progressing slowly, with “very little solar ambition in the drafts.”

Vietnam’s solar could, in fact, be a victim of its own overnight success. Dharmendra Kumar a solar analyst with IHS Markit, now a part of S&P Global, says that he understands that some 3 GW to 3.5 GW of the projects developed under Vietnam’s FIT programs are not grid connected or generating at full capacity.

“What is happening now is that the government is doing checks, one after the other, on all of the projects,” says Kumar. “I think that not all of them have been installed, or maybe installed in a hurry or in a place where nearby grid connection is not available. Putting the grid connection will cost and will make the projects economically unviable. There was a rush to install.”

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

2 comments

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.