Sydney-headquartered solutions technology company Neara co-founder Jack Curtis has responded to the New South Wales (NSW) Budget’s $2.1 billion (USD 1.3 billion) allocation for new transmission projects, saying the opportunity to boost capacity of existing networks is possible with smarter grid solutions.

In doing so, he told pv magazine, the additional capacity would complement the country’s evolving energy mix while also derisking reliance on new transmission projects that are at risk of not being built on time or at cost.

Acknowledging the NSW Budget reinforces the state’s commitment to a renewable energy future by fast-tracking transmission to connect generation projects with the renewable energy zones (REZs), Curtis said the existing transmission network offers a bridging opportunity to manage the complexity of clean energy sources entering the grid.

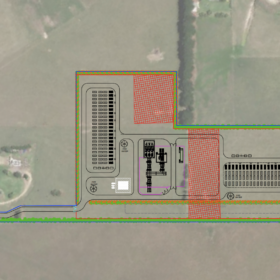

Image: Neara

“The issue is more about the relative allocation of focus and capital to the two solutions to solving grid constraints. The first one is you build a new grid of transmission projects, of which there’s about $20 billion allocated through Rewiring the Nation to unlock 5, 10, 15 GW of renewable generation,” Curtis said.

“And then you look at the existing grid, which potentially has as much capacity, but has nowhere near $20 billion of capital allocated to it.”

Curtis said he thinks there’s an increasing awareness the likelihood of getting to current energy policy goals by relying on new transmission being built on time is very low.

“So, what else can we bring to bear? The existing grid has a lot more of a role to play but really quite nascent in the journey of enabling that from a policy point of view, from a funding point of view, and from a industry coalescence point of view,” Curtis said.

Policy and reliability risks

A policy risk Curtis identifies is the certainty that enough network capacity is available and accessible just to take the generation, though generation itself is well supported by state-based programs and federal schemes like the Capacity Investment Scheme (CIS).

“It’s all very well to solve the generation side of the equation but if you can’t connect it in time because there’s not enough capacity, it’s kind of pointless,” Curtis said.

“The other risk from a just general reliability point of view is that the same constraint is preventing new energy sources coming into the system, while those have been delayed, old energy sources like coal supported by coal fired power plant, which are quite literally on their last legs, there potentially going to be some crossover period where unless, it’s bridged by gas, which is a reliable generating source, you’re going to have this kind of structural instability in the generation profile.”

He forecasts that the use of gas will be an outcome – which means renewable and policy goals supporting the energy transition will be delayed – unless other solutions are found to unlock the constraint issue faster.

Barriers

“I think there’s an element of what is well understood and what is known is sometimes easier than asking, ‘why don’t we just try and make it less constrained?” Curtis said.

“The irony is that there’s actually not just a lot of potential on the existing network but also a lot more generation potential on the assets that would be unlocked by looking at the existing network. Specifically, things like distributed energy resources, behind-the-meter and lower voltage generating solutions.”

He said the strategy of large transmission investment to enable large generating projects to be built and connected is ‘just a well understood solution’ and so attempts to resolve constraints are met with a ‘just spend more money on it to accelerate it’ response.

“And, there are natural limitations to projects such as social license, logistics, execution, supply chain risk, and availability of labour force. There’s an inner elasticity to how much money you throw at a problem to solve it. At a certain point, it doesn’t matter how much investment you put into it, there are other factors that will constrain the ability for it to be successful,” Curtis said.

Supplementary solutions

A difficulty with regard to supplementary solutions is the requirement to deal with hundreds of thousands of different data points, Curtis said.

“Instead of one big transmission line, you’re now dealing with hundreds of different areas of the network that could be augmented, that could be analysed and unlocked, and then you’re dealing with hundreds, if not thousands of different generating inputs.”

“Instead of building 3 GW of large scale solar and wind, you’re potentially looking at hundreds, if not thousands of projects of distributed solar or battery or electric vehicles operating as vehicle-to-grid (V2G), and so that’s why the complexity problem has been hard to solve today,” Curtis said.

“How that gets solved is by bringing all those inputs together in an integrated lens. Right now a lot of the components that support different parts of that equation operate in isolation, so there are other software companies that model what comes out of solar rooftop or what comes out of someone’s behind-the-meter asset.”

“That information is not being put together in a way that the network can see that information and then say, ‘all right, now I know what’s coming, I can have fewer export constraints on what I actually allow into the grid’, or, ‘all right, now we’re going to take that energy and run it somewhere else’.

What Neara, and other solutions do, is bring the thousands of data points together in one integrated lens, where policymakers can see where the optimal configuration of the generation, network and load components are, and more efficiently allocate capital to those projects.

“In defence of policymakers, it’s hard to deploy capital fast enough to solve this problem with the same amount of time and effort and resources as you would a large generating network project,” Curtis said.

“The solve for that is to enable policymakers and stakeholders that deliver these projects, to have one integrated holistic view, so the ability to allocate capital to hundreds of projects is as efficient as allocating capital to far fewer large projects, both on the network generation side.”

Regulations

Curtis suggests regulatory change needs to occur to enable the shift in policy and funding allocation to work from both economic and energy generation perspectives.

“If the regulatory landscape doesn’t evolve to enable that, that could be a fairly unfortunate kind of blocker and end the realisation of what would be a very de-risking component to the energy transition,” Curtis said.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.