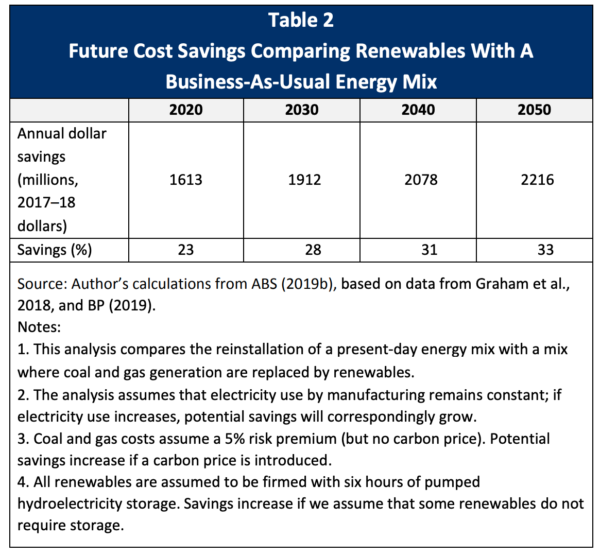

Australia’s manufacturing sector could save $1.6 billion a year, or 23% of its energy costs if Australia’s current coal- and gas-fired electricity were replaced with renewables, and those savings will become greater over time, given the constantly falling cost of renewables-based energy production.

Powering Onwards: Australia’s opportunity to reinvigorate manufacturing through renewable energy, a new research paper by economist Dan Nahum from The Centre for Future Work at The Australia Institute (TAI), finds that by 2050 the transition to a renewables-powered grid would save manufacturers $2.2 billion per year (in constant dollar terms) — or 33% of their bills compared to the current energy mix.

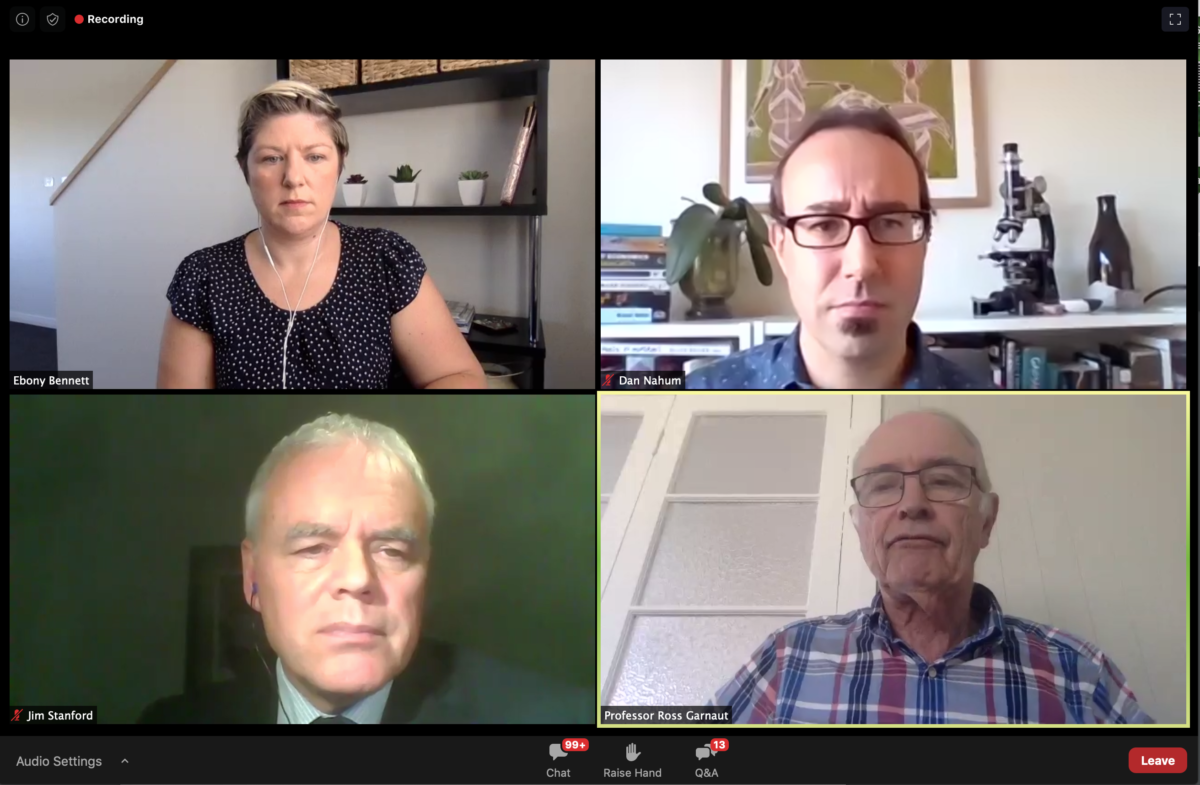

“Covid-19 has been a really important wake up call for Australia, in terms of why we need a resilient manufacturing industry,” said Nahum in a TAI webinar held on Friday, hosted by Ebony Bennett, Deputy Director of TAI; and in which respected economist, Professor Ross Garnaut, author of Superpower: Australia’s low-carbon opportunity, and Dr Jim Stanford, Director of the Centre for Future Work, participated.

Professor Garnaut introduced the paper saying Australia had “muffed things a bit in the past” by failing to maintain a strong manufacturing industry and instead relying on income from the export of resources; but said that by leveraging its global advantages, the country could capitalise on a convergence of factors in the recovery from Covid-19.

“We’ve got advantages of a highly skilled, well-trained, well-educated population,” he told webinar attendees, saying that these are already the characteristics of highly productive manufacturing countries such as Germany, “the world’s biggest exporter of sophisticated machine goods and so on; it’s a high-wage country, a high-social-security country, but competitive because of its skills and the education of its labour force.”

Australia’s definitive advantage, if the nation can grasp it, will become increasingly important over coming decades. That is, “We have by far the richest combination of solar and wind resources” with which to power a manufacturing-led recovery and thereby also “avoid climate instability which will be very dangerous to our standard of living”, says Garnaut.

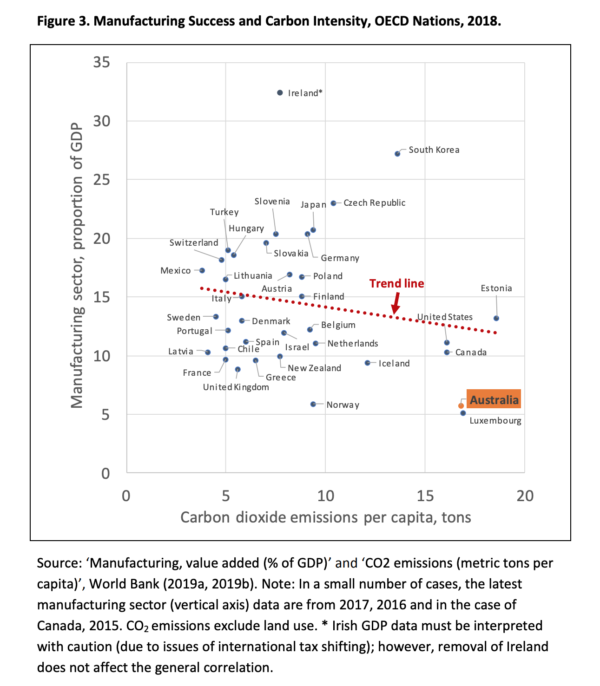

Nahum places Australia on a map of OECD nations, rated according to current manufacturing success and carbon intensity:

Image: Centre for Future Work

“We’re down in the bottom right hand corner with Luxembourg,” in the “worst of all worlds”, said Nahum in the webinar.

As a highly carbon-intensive country, Australia gets minimal bang for its emissions buck: “We’re like a petro state” despite our amazing renewable resources, says Nahum, who adds, “It’s very much a policy choice that we occupy this space.”

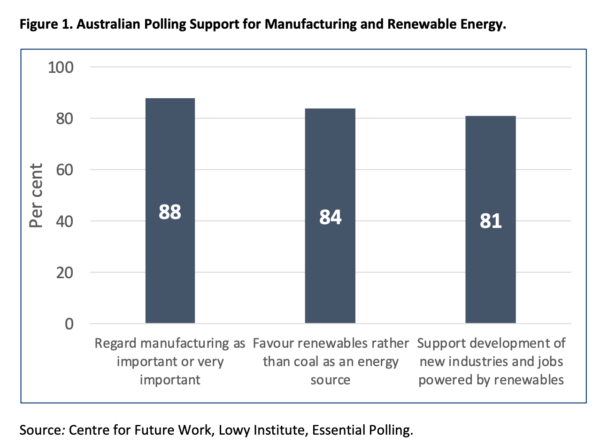

What the people want

And yet, Australians are known to express a very high level of agreement (88%) on the importance of local manufacturing, and support development of new industries and jobs powered by renewable energy (81%), writes Nahum in Powering Onwards, citing 2019 polling by the Lowy Institute.

“This indicates that this is a politically appealing dual objective for policy makers,” he writes.

Image: Centre for Future Work

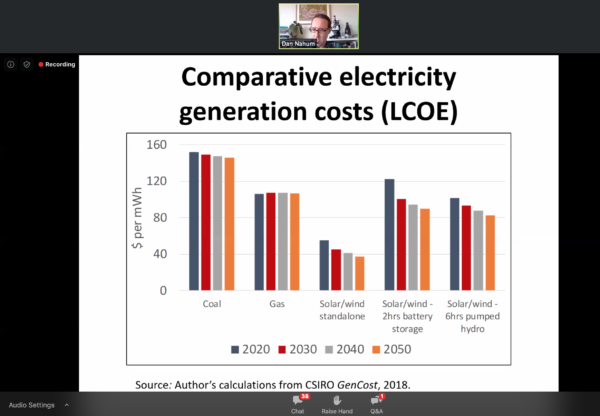

The Centre for Future Work calculations of savings of between $1.6 billion and $3.5 billion conferred by fuelling manufacturing with renewable energy is, moreover, conservative, since its estimates of levelised cost of energy (LCOE) “assumes that all renewables are fitted with 6 hours of pumped hydroelectricity storage”.

Image: Centre for Future Work

Savings would be greatly increased should a carbon price be imposed, or if lower-emissions technology such as carbon capture and storage were mandated for coal and gas plants. And the analysis assumes that manufacturing demand for electricity will remain static — that Australian manufacturing will not grow in line with some of the tantalising opportunities outlined by Nahum.

Cases in point

He cites well-known examples already in operation, such as BlueScope Steel’s seven-year power purchase agreement (PPA) with ESCO Pacific’s 175 MW Finley Solar Farm. The generator, near Albury, New South Wales, and BlueScope’s Port Kembla steelworks are not co-located, notes Nahum, “nor do they need to be; rather, the PPA matches incremental power inputs to the grid with an equivalent demand elsewhere on the grid” and “will supply approximately 20 per cent of BlueScope’s energy requirements.”

He refers also to Rio Tinto’s announcement that it intends to power its Koodaideri iron ore mining operations in the Pilbara with its own 34 MW solar farm and 12 MWh battery, to lower costs and cut emissions.

The opportunities in both conventional and green-hydrogen-based steel production are featured in Powering Onwards, with Nahum pointing out that Australia currently pays “extra for companies and workers overseas to produce steel, a critical and utterly ubiquitous commodity, from Australian iron ore”. You’ve read it before.

But not everyone will be aware that German industrial giant Siemens has recently demonstrated the use of hydrogen in steel manufacturing to replace the use of coking coal. Its hydrogen steel plant is expected to be operational at the end of 2020, “and Siemens is building a wind-powered electrolysis plant to provide hydrogen, to be used initially for the partial coking of steel”.

Nahum’s list of existing and planned projects reminds readers that these scenarios are not science fiction. If Germany can produce hydrogen-based steel, then Australia with its far greater renewable resources and highest-grade homegrown iron ore, must be able to produce a competitive product.

Refining of aluminium, zinc processing, manufacturing of food products, production of green hydrogen to fuel transport and heating, electric vehicle (EV) manufacturing, processing of Australia’s rare earth resources — the benefits of each to Australia’s economy are outlined in the paper.

Bringing it all together

Among the most enticing examples in terms of integrated vision and jobs creation is that of Tesla’s Nevada-based Gigafactory, which uses co-located solar arrays to power production of lithium-ion home-battery packs and sub-assemblies for Tesla EVs.

“This will allow Tesla to reduce costs on battery production … mitigates Tesla’s reliance on the supply of batteries from its external supply chain” and when completed, “the Gigafactory will employ an estimated 6,000 people,” summarises Nahum.

With its abundance of lithium and solar resources, Australia could be part of the global plan for Tesla Gigafactory rollout.

If batteries, why not solar panels?

Expertise in solar cell and panel manufacture runs deep in Australia; the country’s research and development centres such as the University of New South Wales School of Photovoltaic and Renewable Energy Engineering have been instrumental in growing China and Korea’s solar panel manufacturing capabilities

“With appropriate support and planning, there is no reason that much more of the coming expansion of Australian demand for solar power equipment,” could not be translated into Australian manufacturing opportunities, writes Nahum, who adds, “Using Australian materials to manufacture panels in Australia would also minimise transport costs.”

More research backs the imperatives

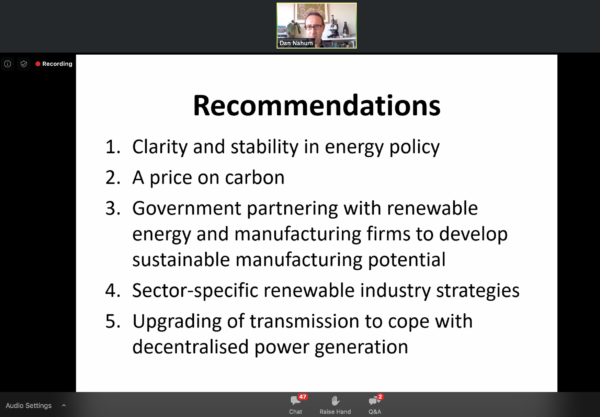

The Centre for Future Work recommendations, summarised below, are not new — many have been arrived at by other research projects, and must by now be ringing, mantra-like in the ears of policymakers.

On Friday, Nahum described his paper, which was initiated pre-Covid-19, as a timely piece: “The government certainly knows that something is required … they’re talking about things like a gas-led recovery; they’re openly discussing using economic planning for the benefit of people who own fossil fuel companies, but they’re not quite sure what to do…”

In the post-Covid-19 economic landscape, as Australia tries to avert a depression, says Nahum government must choose: “How do we want to provision our society going forward? … Manufacturing as part of that story adds a lot of value to our endowment of resources” — educated people, raw materials and low-cost renewable energy.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

I for one welcome discussion of green mining (mining, but with nice explosion-proof electric power put in, environment purefaction that’s quite the stack of technologies without being virtual, and mineral factoring that’s an inspectable glory of keeping by itself,) that has been glossed over quickly in this particular…call for JVs. Once there’s a bloom of desalination to 800 miles in and a weatherable never-never, good things and their gains in natural value will be fine to behold. Bit of a learning curve for some kind of entity there; not going to call it the ‘Fintech Gig Ecology.’