From Wood Mackenzie’s APAC Energy Buzz

China’s future could be less reliant on the rest of the world

At its core, dual circulation is about relying less on the outside world. With the pandemic still raging, relations with key trading partners such as the US damaged, and the rhetoric of deglobalisation continuing to reverberate, China’s leadership appears to have looked at its enormous domestic market and seen something far preferable.

But if China’s economy is turning inwards, what does this mean for the global economy? Will global supply chains be transformed? And is dual circulation a boon for China’s energy transition as Beijing seeks to reduce dependence on imported energy? To get some answers, I spoke with Yanting Zhou, our China chief economist.

Differing roles for ‘domestic’ and ‘international’ circulation

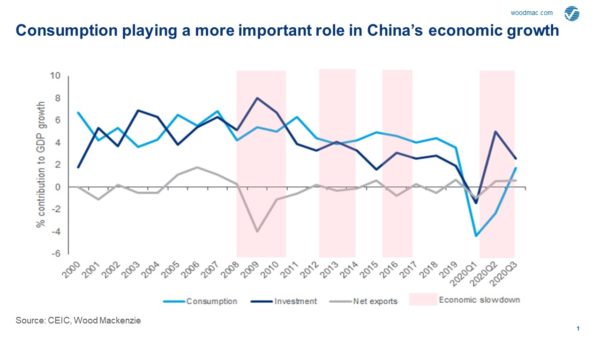

To approach this simplistically, we can think of dual circulation as placing economic activity into two distinct buckets – domestic and international. With global trade continuing to struggle and exports as a percentage of China’s GDP declining for years, China’s leaders have for some time believed the domestic economy offers greater stability and upside.

A further decoupling of trade between the US and China would accelerate this. In addition, focusing on the development of its own technology allows China to reduce risks to domestic manufacturing by reducing dependence on supply chains in areas such as semiconductors and other essential technologies.

Domestic circulation will be delivered through upgraded domestic demand alongside rising investment in several strategic sectors to secure supply of crucial products. To be clear, the country isn’t closing the door to international trade – far from it, as China’s leaders have been keen to stress – but is crystallising broader thinking around how China itself must support greater innovation and resilience.

China has achieved much already, mainly due to decades of strong economic growth and investment in R&D. But the strategic objective of domestic circulation has taken on greater urgency as tensions with the US have increased.

Now for the hard part

Increasing reliance on domestic consumption may sound straightforward given the size of China’s population and economy. But the reality is that domestic circulation will require a major redirection of capital, resources and labour to drive domestic demand, and this comes with significant risk.

I see two key ways to boost consumption. Firstly, supporting the low-income population. China may now officially be in the middle-income country group, but a massive wealth gap remains, with more than 600 million people on a monthly income less than US$150.

How can this be achieved? Ultimately, it will require increasing urbanisation and that isn’t easy. To obtain the full benefits of living in China’s cities requires a ‘hukou’, or residency card – think of this as an all-important swipe card to access schooling, healthcare and housing. In most cities these are incredibly tough to get hold of and are linked to education level, work experience and annual quotas. The 14th five-year plan will have to tackle what is a hugely emotive topic in China.

Secondly, rising domestic consumption can only be achieved by reducing the debt burden on China’s middle class. By far the major source of debt is mortgages, driven by China’s seemingly endless rounds of housing booms. Policies aimed at cooling investment have had some impact, but with property a central pillar of the Chinese economy – and land sales the major contributor of revenue to debt-laden local governments – this is easier said than done.

The strategic focus on security

Domestic circulation isn’t just about encouraging demand. It also includes a strategic focus on strengthening self-sufficiency across the domestic economy. Energy and food security are critical to this.

Let me first quickly comment on food security. China is rightly proud of its ability to feed itself. But this is achieved partly through trade protection and subsidies to farmers. One area where China is far from self-sufficient is soybeans, with the US the major supplier.

This has implications for future energy demand. China’s investment in agriculture will increase, with a focus on improving efficiency and mechanisation. This will in turn free up labour and drive urbanisation, with a corresponding impact on diesel (reducing agricultural demand) and electricity demand (rising as urbanisation grows).

Implications for the energy sector

Energy security may now be firmly back on the agenda but there is no quick fix to China’s rising reliance on imported energy. As such, I don’t expect to see China pull back from support for overseas investment in the energy and natural resources sectors. Too much of the domestic supply chain relies on imports – and will for years to come.

Dual circulation also creates a paradox for China’s energy planners. By prioritising domestic production and consumption, the policy will drive demand for energy, much of which will need to be imported. Of course, the government will direct investment towards specific sectors including green hydrogen, solar PV manufacturing, energy storage and electric vehicles, but the fruits of this investment will take years to show. Until that time, hydrocarbons will remain the backbone of China’s energy system.

Investment in technology will transform supply chains and support decarbonisation

Ensuring greater self-sufficiency in critical technologies is a core mantra of the 14th five-year plan. The huge strides China has already made in technology have often been achieved by purchasing from the rest of the world. Trade wars put this at risk, as seen by the restrictions on US semiconductors and other technology. I think we can expect considerable direct investment into domestic sectors that help the country achieve technological self-sufficiency.

This has implications for energy. Renewable power, new energy mobility, energy storage and ultra-high voltage transmission will all be prioritised. These sectors will create major upside for battery raw materials and copper as China looks to build its energy transition from within. This will also enhance energy security and reduce risks from long supply chains. China’s long-term decarbonisation strategy fits perfectly with these goals and hence its prominence in 2020.

APAC Energy Buzz is a blog by Wood Mackenzie Asia Pacific Vice Chair, Gavin Thompson. In his blog, Gavin shares the sights and sounds of what’s trending in the region and what’s weighing on business leaders’ minds.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those held by pv magazine.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.