From pv magazine global

pv magazine: Prof. Overland, this year we have seen a large number of governments, industrial conglomerates and big corporations announce new plans or strategies to make hydrogen into a feasible option for the energy landscape in the decades to come. We have seen the setting up of potential hydrogen clusters, hydrogen alliances, and many partnerships among heavyweights within industries of different kinds. However, it is still not clear whether the price of hydrogen will drop easily, regardless of whether green or blue. Do you believe these massive plans will be enough to make hydrogen succeed?

Indra Overland: Although it is not the first time there has been enthusiasm about hydrogen, the enthusiasm is more intense, widespread and concrete this time around. The context is also much more conducive this time, with the Paris Agreement in place, policymakers around the world taking climate change increasingly seriously, and an experience of cleantech companies doing very well on stock exchanges. However, ultimately intentions, plans and roadmaps will not be enough to turn a hydrogen economy into reality. It will depend on hydrogen becoming cost-competitive vis-à-vis other solutions in several areas, such as seasonal/grid-level energy storage, high-heat industrial processes, heavy road transport, shipping and aviation. If hydrogen does turn out to be the cheapest option in several of these areas, its future will be bright. If it only wins in one area, it is probably not going to be such a big deal although it could still have a market.

Are there countries that may be better positioned than others for the hydrogen economy?

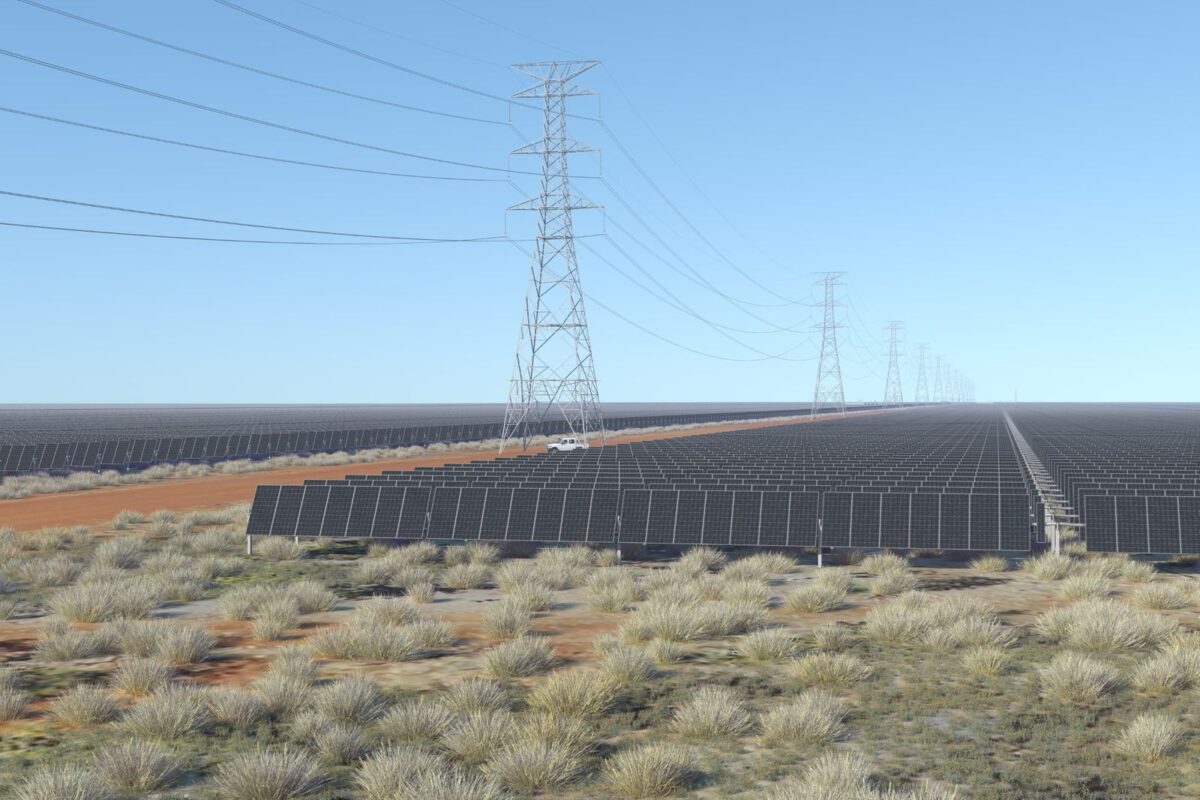

As I showed in recent research, some countries with abundant renewable energy resources have comparative advantages in the production of green hydrogen, that is to say, hydrogen produced by hydrolysis. Space is also an important factor, because solar and wind facilities require a lot of space. Thus, a country such as Algeria might have a significant advantage and become a net exporter of green hydrogen to the European Union, especially if its existing natural gas pipelines can be repurposed for hydrogen. However, current levels of efficiency for green/hydrolytic hydrogen are not very high, so this picture is not clear as of today.

Assuming that electrolysis prices will fall enough to bring green hydrogen into the picture, what consequences should we expect in geopolitical terms? In your previous interviews with pv magazine, you stressed more than once that wind and solar, and increasing rates in the electrification of transport and mobility, would make countries less dependent on each other and on energy imports. Could hydrogen maintain certain levels of energy-dependency?

This is not an unlikely scenario. However, as I showed in one of my research [papers], such green hydrogen exporters will always be competing against their own customers! What I mean is that the exporters have an advantage in terms of renewable energy resource abundance and available space, but this advantage is not absolute, as the customers also have the opportunity to produce their own hydrogen if imports become too expensive. All countries have some renewable energy resources, even if they are not very evenly distributed. Thus if there is a growing international trade in hydrogen resulting in increased energy dependency between some countries, it is still not going to be like the oil dependencies of old between an exporting country that has a lot of oil and an importing country that has no oil.

There is currently a lot of interest in hydrogen from big utilities and fossil fuel companies, as many of them may keep using their gas infrastructure to transport and sell hydrogen, or even use gas to produce it. Do you believe that their support for one technology or another will be crucial in deciding the world’s future energy landscape?

My impression is that the climate policy momentum is too strong to be manipulated by fossil fuel companies in the long run. They might be able to temporarily greenwash something or cultivate enthusiasm about something that is not quite clear yet, such as the economics of various hydrogen options. But in the longer term it will boil down to a competition between concrete zero emission technologies and their cost-efficiencies. However, in this competition one should not write off blue and turquoise hydrogen yet. Blue and turquoise hydrogen are made by capturing carbon from natural gas and pumping the carbon back into the ground or using it for other purposes. This type of carbon capture will probably continue to be cheaper than carbon capture from exhaust fumes and may turn out to be more cost efficient than green hydrogen. If existing natural gas pipeline infrastructure can also be repurposed for hydrogen without costs becoming too high, it could become a very interesting option for quick decarbonization.

Hydrogen poses a chicken and egg problem: should we first create demand from heavy industry and transport and then build up a hydrogen generation fleet or rather first set up the latter and then stimulate demand?

So many things in the world are chicken and egg problems, but I don’t think hydrogen really is one of them. It was an intractable chicken and egg problem when it was thought that passenger cars would be the main initial market for hydrogen, but that was a big mistake as lithium ion batteries are much more suited for passenger cars and hydrogen is much more suited for other things, like temporal grid-level energy storage and high-heat industrial processes. And for those areas there is not a significant chicken and egg problem, one just has to make a bet on hydrogen and see whether one is able to compete against the alternatives.

The race for hydrogen may challenge the perspective of a fully electrified world. If producing green hydrogen will prevail, do you believe we may see less need for battery-based energy storage?

Yes, if green hydrogen costs fall significantly and enable it to compete against other storage solutions, there will necessarily be less demand for the other storage solutions. However, with the extreme growth in electromobility that I expect—which I think will outpace the expectations of most actors—there may be so much demand for lithium ion batteries for vehicles that this frees up the seasonal/grid storage for hydrogen, maybe also some other areas like aviation.

Eventually, what kind of countries may decide to have the highest rates of other types of storage, electromobility and electrification and which ones may have a stronger preference for hydrogen?

Good question. I don’t know. Maybe whatever it makes sense in one place will make sense everywhere else too, so that there is not much geographical variation.

Compared to batteries, green hydrogen is currently cleaner. Would this represent an advantage?

Yes. However, battery technology is undergoing rapid change. For example, cobalt is already on its way out. Thus, the lifecycle emissions and other social and environmental issues connected with batteries are going to change. So hydrogen has an advantage, but it is shrinking and we don’t know how much it will shrink in the future.

Is a clash of technologies and big economic interests in sight? Should we avoid it or is it inevitable?

Technologies are going to be key, and competition over hydrogen-related technologies should become pretty fierce. However, this is not exactly war, more like the competition between Apple, Huawei and Samsung in mobile telephony.

Solar and wind would benefit from both scenarios, as well as the coexistence between the two trends. Do you believe that, under these circumstances, we may see an accelerated decline of fossil fuels? Which would be the geopolitical consequences of this accelerated scenario?

If there is one thing that I am confident about it is that solar and wind will grow. At the moment, floating offshore wind is particularly dynamic, but there is an awful lot of research going on into different photovoltaic technologies that could potentially give solar a massive boost. Hydrogen is another likely piece in this puzzle of the whole energy transition that could help it accelerate.

In our most recent interviews, you highlighted repeatedly that geopolitical changes do not occur too quickly. Don’t you believe that this year, with the Covid-19 crisis and the arrival on the scene of hydrogen, an acceleration could have been triggered?

I am not sure that hydrogen will cause any dramatic acceleration in the energy transition, though more clarity on blue and turquoise hydrogen or a cost-cutting technological breakthrough on green hydrogen could do that. What I think is more likely to cause abrupt change is stranded fossil fuel assets. Financial markets are like flocks of sheep. When they swing from one thing to another it can get very crowded at the gate. I am glad I don’t have any shares in ExxonMobil to put it that way. Countries whose economies are largely based on fossil fuels could experience serious shocks in the coming two to three years. This also means that the question of blue and turquoise hydrogen is decisive. If blue and turquoise hydrogen are not viable options, it will reinforce the fossil fuel collapse. If, by contrast, blue and turquoise hydrogen turn out to be cost-efficient, the countries with the largest natural gas reserves could have very bright prospects indeed.

In previous interviews with pv magazine, Overland discussed geopolitical issues related to the GeGaLo Index itself, the myths around the geopolitics of renewable energy, and the combination of solar and hydropower. He has also talked about countries such as China, the United States, Russia and Saudi Arabia, as well as technologies like storage, super-grids and the energy transition in general.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.