From pv magazine 06/2021

The draft rule determination, or guidelines for all players in the industry, handed down by the AEMC in March focuses on Distributed Energy Resources (DER) – and follows nine months of consultation with stakeholders. The final determination for DER, following a public consultation process, is set for July 2021. The current format in the draft includes a fee to be paid by energy-exporting households. It’s quickly been dubbed a “solar tax” by critics.

This marks the second attempt by the AEMC to establish an export charge. In 2017, the regulator also published a draft report on the Distribution Market Model, with reasoning for a solar tax. After a backlash, the final report removed the tax.

Now with a second effort, how bad can it be?

The Australian way

The AEMC’s draft rule determination didn’t go unnoticed. Interest groups were quick to disparage the Australian government’s approach to renewable energy. Australia, the sunniest continent in the world, has shown a perplexing hesitancy to fully embrace renewables.

However, rooftop PV uptake by households has been a true bright spot in the country. The AEMC’s own figures suggest that around 20% of all grid connected customers have rooftop PV installed, and are able to sell excess electricity into the grid. As recently as 2007, the same figure was less than 0.2%. By 2030, the nation’s small-scale solar generating capacity is expected to triple.

Part of the success has been generous subsidies and feed-in tariffs, with billion-dollar grants in the late 2000s and early 2010s dubbed “middle-class welfare” by critics. However, with the industry given a kickstart by governments, success followed through growing awareness, improved installer experience and expertise, economies of scale, and indirectly related technological advancement.

On the other hand, Australia has offered limited subsidies for other green initiatives. Despite Australia’s rich offshore wind resource, offshore wind projects have been slow to get off the ground, with the first project, a massive 2.2 GW scheme, only approved in 2019.

Electric vehicles account for just 0.7% of total Australian car sales in 2020, compared with 10.7% in the UK, and California’s 8.%. Despite this, the state of Victoria, proposed an AUD 2.5 cent/km tax on electric vehicles, described as “the worst in the world.”

Behind the “solar tax”

The AEMC announcement said the driving force behind the rule change is the shift from one-way power delivery, to rooftops delivering large-scale exports to the grid during the day.

The AEMC states: “The system wasn’t designed for power flowing both to – and from – consumers. Because of this, so much solar potential is locked away. Not everyone can export their solar energy because of daytime ‘traffic jams’ on the network.”

A strong critic of the draft rules, Professor Bruce Mountain, Director of the Victoria Energy Policy Centre at Victoria University, argued to pv magazine that driving forces were politically motivated.

“What’s really behind it, I think, is [that] the first job of government is to look after government. It’s central authorities trying to centrally coordinate things; not keen on a distributed power supply and microgrids; the devolution of electricity to local production. Something like that, where they are not in the centre, nor controlling, goes against their DNA.”

Mountain insisted the evidence doesn’t stack up. “I’ve put all of my arguments [against this draft ruling] on the evidence. The evidence is that connecting distributed solar costs two-thirds of nothing. It’s not arguable. There is no cost rationale for this.” Mountain also argued that Australia’s retailers just “flat out don’t like solar.”

“The retailers, generally, don’t like solar. They’d obviously rather customers were buying from them directly. And they’re further worried about customers taking a battery … and when they have a battery, customers use about everything they produce. And they then make no money out of customers. And solar is seen as a stepping stone along the way, and they don’t like it.”

“The reality is, it’ll make solar a lot less attractive. The social license of the market will be badly damaged.”

What’s proposed: the detail

While the AEMC draft ruling only allows for the distribution networks to pitch a new method of pricing during the regulatory phase, it does model likely costs:

A household PV installation of around 4−6 kW, currently earning around $970pa on average, would incur a AUD 70pa charge.

Smaller systems of around 2-4 kW, currently earning an average of around $645pa, may earn around $30 less, on average, from their exports.

The changes, as currently presented, would take some years to affect households.

Following the AEMC’s final ruling, distribution networks in each state will need to submit new plans for determinations by the Australian Energy Regulator. The next renewal of these policies happens on an individual state-by-state basis – with the states’ renewals occurring between 2024-2026. Therefore, possible export pricing changes are as much as five years away; if the states agree.

State support splinters

Already, and unusually, state support for the AEMC’s draft ruling is unravelling. Two states, Victoria and Queensland, have signalled their opposition to the tax.

Victoria opposed the move during the AEMC’s initial consultation process in September 2020, with the department of environment, land, water and planning noting in its submission: “The Victorian Government does not support export charging, as the case for implementing this element of the proposed reforms has not been demonstrated at this time.”

Queensland’s state energy minister, Mick de Brenni, also opposed the rule change, and was quoted in an online newspaper last week as saying, “My department is preparing a response to the proposal and I expect it will indicate that system-wide measures, especially investment in more storage, will encourage more solar and are preferable to the proposed rule change.”

Professor Mountain explained that because the AEMC was established by the states, public disagreements are rare, even if private discussions are robust.

“The states generally don’t want to have a blatant fight with regulatory authority, most notably with the AEMC, which the states set up in 2005 as an accountable body, and they agreed to the AER on the condition the AEMC make the rules,” said Professor Mountain. “They are loath to argue with it publicly.”

PV disincentivized

From a sample of Australians polled by pv magazine Australia, households haven’t fully comprehended what might be to come but are worried.

Chad Bennett, a new property owner in Newcastle, NSW, said that he’d been considering PV installation on his recently purchased existing home, until now.

“An upgrade to solar makes sense on a number of fronts for us, and it’s something that we’re definitely considering in the near future,” said Bennett. “Any pricing changes or tax would definitely have an effect on the decision, given the installation would be a substantial outlay. It’s disappointing that something positive could be disincentivized.”

Another prospective solar buyer, and engineer, Avinash Raju, confirmed his opposition to any tax.

“I am in fact a huge fan of renewable energy, particularly solar,” said Raju. “I was annoyed about the fact that they even reduced the export rate in the first place, let alone this tax on the sun they are proposing.”

“I believe that a well-engineered smart grid system has the capability to manage any export problems. But taxing the solar owners won’t solve this and will hurt Australia’s efforts to increase renewables.”

Spain’s infamous PV tax

Spain’s so-called “sun tax” (or solar tax) era is now over, but it shows the dangers of disincentivising solar. In Spain, a self-consumption tax was established in 2015 by the then conservative government, which argued that a “backup charge” was required to take into account the availability of the electricity grid.

Jose Donoso, Director General, Unión Española Fotovoltaica (UNEF), told pv magazine, “Everyone knew this tax was to ensure solar and self-consumption would grow more slowly.”

In effect, the tax levied a charge on every kilowatt-hour generated even if it was used for self-consumption. In an analogy, Donoso explained it would be like having an apple tree yet having to pay tax on each apple you ate.

“It was an irrational tax, on something that came free from the sun. We spoke and campaigned with everyone regarding this. Once we explained it was a tax, a tax on the sun, everyone understood it was unfair,” said Donoso. “The other side was that households almost completely stopped installing new PV.”

“The government at the time said self-consumption was just for rich people, and therefore, the poor people [without PV installed] would need to pay for rich people. But we showed how the PV installations would reduce the electricity price for everyone. Now, again, after this tax was removed, solar is growing.”

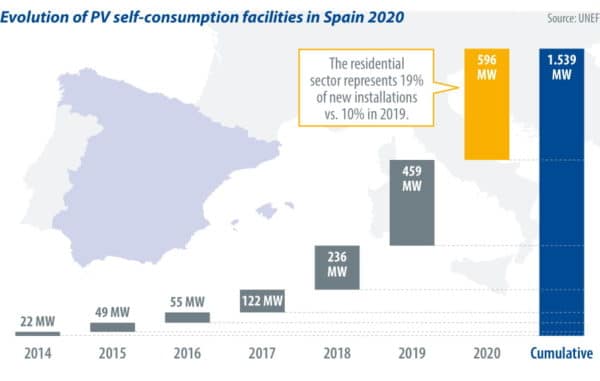

The data agrees: Spain doubled current installed capacity in the first year post-tax and continued to grow.

Unfair application

Spain still has a general generation tax in place, called the Tax on the Value of Electricity Generation, a generation tax of 7% applied uniformly on all who export power, from small PV installations to large generators of all types. Donoso confirmed that UNEF has less opposition to this tax, as it is applied to all.

In the state of Minnesota, in the U.S., a tax of $1.20/MWh produced applies to installations larger than 1 MW. Others under this nameplate generation capacity are exempt.

In Australia, Mountain explained that this proposed tax will only be applied to households and residential installations, and not on large wholesale generators, and that would be a bad look once scrutiny intensified.

“The politics of charging for network usage at a retail level, but not wholesale level, stinks. You can just picture the shock jocks on the radio, calling the state minister in, saying: ‘So you’re happy to charge households to use the grid, but these big generators, you’re not charging, can you justify it?’,” said Professor Mountain.

The AEMC’s initial deadline for feedback and submissions was May 13, however, that has subsequently been extended out to May 28, with the regulator noting “strong interest.” A public forum will also be held on May 20.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

1 comment

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.