Electricity markets were designed to be one-way, flowing from big power stations, down the poles and wires, and into our homes, farms and businesses.

In New Zealand, we’re heavily reliant on our world-leading hydro dams – most of which are a long way from where that energy is needed – while geothermal offers a solid base, wind and solar farms bump up the renewable supply, and gas and coal make up the shortfall.

But our future energy system could look a lot different.

As Dr Saul Griffith said at the release of the Investing in Tomorrow paper, which was co-written with the chief economist of the Reserve Bank Paul Conway, all the electric vehicles in the country will eventually be one of New Zealand’s biggest batteries; all the rooftop solar on our homes and farms will be the country’s biggest generator by far; and just as the hydro dams and transmission lines of the 20th Century were able to access concessional finance because they were seen as critical energy infrastructure, these customers need access to concessional finance because they should also be considered critical energy infrastructure.

Put another way, why does the New Zealand taxpayer back the returns and profits of the companies that build our poles and wires, but won’t back the financing of a single mother installing solar and a battery, which will both save her money and benefit the nation’s energy system?Or why don’t we back farmers to install solar to run their irrigation during summer and reduce the need to burn coal for electricity in winter?

The rules of the game need to change, the investment assumptions and frameworks need to change, and the energy system needs to become smarter, two-way and designed with the customer’s best interests in mind.

This is what Rewiring Aotearoa’s ‘Delivered Cost of Energy’ paper explored.

Location, location, location

Generally, the primary objective of electricity markets globally can be characterised as delivering a secure electricity system at the lowest cost. This focus on cost was valid when the vast majority of investment options were grid-based and a like-for-like method of ranking generation options was sensible.

The calculations used to make these decisions, however, need to change to reflect new technologies like rooftop solar and batteries and the value that they offer to customers and the system as a whole.

Proponents of grid-scale plants often argue that bigger is better from a national benefit perspective, due to the lower capital cost (per-MW of installed generation capacity) compared to rooftop solar.

This argument ignores the fact that the value of electricity in New Zealand varies depending on the location of investment (Northland, a province at the top of the North Island, is a good example of this).

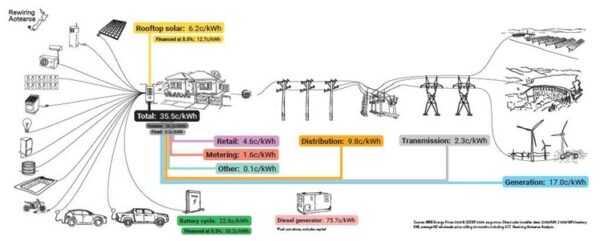

Transmitting and distributing electricity is not free. It makes up around half of a household’s energy bill, while most of the other half is generation. You can see how the large-scale plant tactic of somewhat lowering the generation then taking a profit on it doesn’t necessarily make much of a difference for a home’s bills.

Rooftop solar doesn’t need poles and wires to put energy into your fridge and hot water system so therefore doesn’t need that other half of the energy bill.

On our all-electric cherry orchard Forest Lodge, we use around 900% more electricity than the previous farmer, but with 160 kW of rooftop and ground mount solar and 300 kWh of batteries, about 85% of the power we consume we create ourselves.

Importantly, we don’t take any more power during peak periods – which is one of the biggest factors when making investment decisions in energy infrastructure. In fact, because we export a huge amount back to the grid, we are a net exporter overall and can power about 25 homes. This reverses the need for more poles and wires.

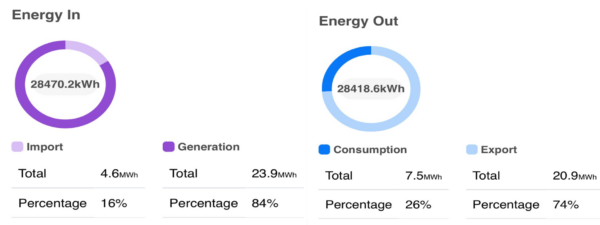

Here is an example of the last 30 days.

We can generate electricity for NZD 7c (USD 4c)/ kW (including the cost of finance), while the average retail price of electricity in New Zealand for the past five years is 26c / kW (the average wholesale price over the last five years is around 15c/kW).

Through a special arrangement with the local distribution company Aurora, I can be paid to export and reduce my demand at peak times. Every battery basically removes a home from peak and exports can remove your neighbours from peak, and this is why we’re advocating for customers to be rewarded fairly for their contribution with the introduction of symmetrical export tariffs. Location and distribution is so crucial because it reduces costs for customers but also reduces the need for expensive upgrades to the poles and wires (mainly distribution).

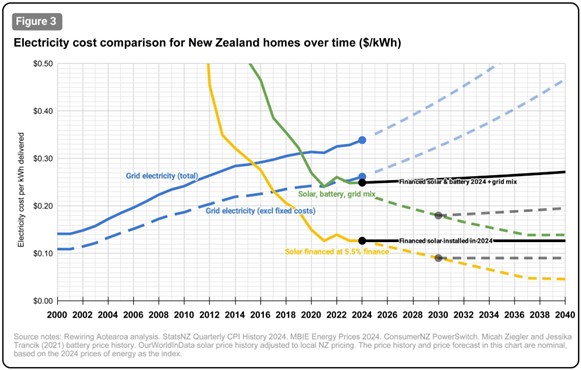

In New Zealand, rooftop solar is now the cheapest form of delivered electricity available to New Zealand households, and while just 3% of New Zealand homes have solar compared to more than 35% of homes in Australia, we’re seeing similar adoption curves – even without the subsidies that kickstarted Australia’s boom.

A lot of a little is a lot and Rewiring Aotearoa’s research suggests that if a 9 kW solar system was added to 80% of New Zealand’s homes the combined generation would add 40% more electricity than today.

If the 50,000 farms in New Zealand did as we did on our orchard, that would be another 60%, which is convenient given one of the government’s aims is to double the supply of renewable energy and it could reach that goal by focusing on existing rooftops.

When it comes to batteries, just 120,000 homes (or five percent of households in New Zealand) with a medium-sized battery could potentially reduce the peak load as much as New Zealand’s largest hydro power station, Manapouri, but only for a few hours when we really need it. These batteries would have enough energy to cover those winter spikes in demand and recharge during off peak times.

There’s a bias towards bigness

The centralised approach is still the dominant philosophy in New Zealand, and elsewhere. It has served us well; it continues to serve us well and we will need plenty more big stuff to be built as we electrify our economy.

We don’t, however, want to overinvest in unnecessary infrastructure upgrades – which will eventually end up on customers’ bills – if we can use our existing assets and modern technology in a better way.

The national discussion about building the ‘right’ plant for the system is anchored around a decades-old framework that assumes it will be directly connected to the transmission grid and will earn the wholesale electricity price for its output. However, today there are over 60,000 power plants on New Zealand rooftops and these need to be factored into the calculations.

These rooftop solar systems don’t earn the wholesale price for their output, they “save” (or avoid) the retail price, which is generally around double the wholesale price.

New technology is changing the economic equation and regulators need to examine the architecture to see if it has in-built inadequacies, outdated assumptions and biases against distributed resources. We believe it does and the unfairness that’s currently baked into the system needs to be removed.

Customers pay retail, not wholesale

In the world of fossil fuels, the price of crude oil is not what matters to consumers. We talk about the ‘price at the pump’ or the ‘price at the bottle’, as that is the price paid by the customer, despite the fact that numerous delivery costs and levies are included in that price. Delivered costs also need to be used when it comes to analysing electricity.

The price of generation is just one part of the electricity cost as there are a range of costs incurred in its delivery. These are not just ‘transport’ costs (i.e., transmission and distribution costs), but also the cost of services provided by intermediaries (e.g., retailers who provide risk management services in the form of predictable tariffs rather than a volatile wholesale price).

To evaluate the ‘value’ of electricity in the distribution network and ultimately at the customer’s premises, it is important to consider the ‘delivered cost of energy’ as faced by a customer. There are costs that exist in the supply chain – from the grid through to the house or business – that would be reduced by an investment in rooftop solar and batteries and these need to be factored in.

Customers who install rooftop solar are likely to be motivated to change their demand behaviour to maximise the use of daytime solar, which benefits them economically. These customers will also be able to effectively shift their solar production from the time it is produced (daytime) into morning or evening peaks through the use of battery storage or demand-shifting, which has value to the system, but isn’t being valued appropriately.

The playing field is not level

Retailers should not make a profit on generation export that is the result of a customer funded

investment, and this is happening when export rates are below the average wholesale price (two of our biggest gentailers, Mercury and Contact, pay just 8c / kW).

At the very least, all homes and businesses should have the option of exported solar being paid the wholesale price, symmetrical peak export tariffs should be mandated and, if distributed resources create greater value (per kW) than grid-connected resources, the regulators should be trying harder to reduce the red tape associated with investment in these resources.

Distribution networks in New Zealand should also be capable of absorbing the exports from significantly more rooftop solar installations than exist today, without significant additional investment in network upgrades.

We can see how this has played out in Australia and there is a long way to go before we reach that stage in New Zealand. The 5 kW export cap is ridiculous, and the government’s proposed voltage changes mean export caps must be removed, especially because the more we export the less coal we will need to burn.

The price of solar and batteries is already competing against grid prices. These prices are expected to continue to drop while grid prices are expected to continue rising. The above chart shows the grid price forecast based on historic grid inflation, but the electricity distribution businesses’ investment, which is set by the Commerce Commission, will significantly exceed this in the next five years. The solid black lines in the chart show solar and battery purchases effectively buy many years’ worth of energy upfront.

Even without fair price signals from the market or government subsidies, rooftop solar and batteries are becoming more popular in New Zealand, as they are in most countries around the world (demand for EVs increased due to a subsidy under the previous government but that has been removed).

The primary reason for that growth is the price. It has dropped so rapidly that it now makes economic sense for most homeowners to install solar and if the system was adapted to reward customers fairly for their contribution to the system, we believe adoption rates would speed up.

We want people to remain connected to the grid and we want generators big and small to be rewarded for the crucial role they will play in our electrified future.

The government’s recent policy statement on electricity talked up the role of households and demand flexibility, and there are also planned upgrades to outdated solar and EV charging standards that will align New Zealand with Australia or other trading partners, and changes that would allow homes and businesses to sell more power back to the grid without having to invest in costly upgrades.

Access to long-term, low interest finance so everyone can access these technologies – and the cost and emissions savings they offer – is a crucial part of the puzzle.

Rewiring Aotearoa is working hard to ensure that the government understands this and stops focusing on overseas trees and unproven technologies to reach our emissions targets.

The fastest way to reduce emissions is by upgrading the millions of small fossil fuel machines to electric equivalents and running them with locally-made renewable energy. And the more of it that is produced where it is generated, the better.

Customers have the potential to deliver the goods when it comes to creating a modern electricity system, but they deserve better. What time electricity is delivered, where it is delivered from and what it costs the customer to have it delivered to their home, farm or business all need to be taken into consideration. Only then will it be fair, and only then will we be creating the cheapest, cleanest and most resilient option.

Author: Entrepreneur and Central Otago cherry orchardist Mike Casey is the chief executive of Rewiring Aotearoa, a think-do tank dedicated to electrifying millions of fossil fuel machines across New Zealand as quickly as possible.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those held by pv magazine.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.