A group of researchers from the University of New South Wales (UNSW) has investigated the impact of different encapsulants on the corrosion-induced degradation of n-type tunnel-oxide passivated contact (TOPCon) modules and have found that some polyolefin elastomer (POE) encapsulants are more prone to cause corrosion than other types.

“In this study, we show that not all POE encapsulants are automatically safe for TOPCon modules,” corresponding author Chandany Sen told pv magazine. “By combining electrical testing, spectroscopy, and electron microscopy, we map out step-by-step how a specific commercial POE formulation can break down under heat and humidity, generate a cocktail of organic acids, and then chemically attack the silver-aluminium contacts until the module loses more than half of its power.”

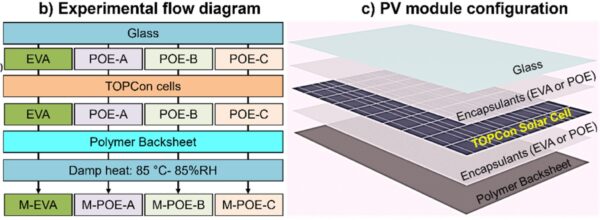

For their testing, the scientists manufactured TOPCon minimodules encapsulated in ethylene-vinyl acetate copolymer (EVA) and three commercially sourced polyolefin elastomers (POE-A, -B, and -C).

Sen said some POE formulations with proper antioxidant and UV‑stabiliser packages remained stable nonetheless. “The key message is that reliability depends on the exact encapsulant recipe, not just on the polymer family label,” she said. “Encapsulants that look very similar on the outside produce completely different outcomes inside the module. One kept the contacts essentially intact, while the other became an acidic environment that severely corroded the metal grid.”

The teams’ research began by fabricating TOPCon minimodules that differed only in the encapsulant. The TOPCon cells in them were commercially sourced, featuring a boron-doped emitter (p+ emitter), aluminium oxide (Al2O3)/hydrogenated silicon nitride (SiNx:H) stack, and a screen-printed H-pattern silver/aluminium grid on the front. On the rear side, there was a silicon dioxide (SiO2)/phosphorus- doped poly silicon (n+poly-Si)/SiNx:H stack and a screen-printed H-pattern silver grid.

All cells were soldered on both sides to connect ribbon/tabbing wires to the cell busbars, forming an 8-cell string. Subsequently, all were encapsulated using different materials, including commercial sources.

According to the manufacturers’ datasheets, the EVA and the three POEs have optical transmission of at least 90%. POE-C exhibits UV-cut features, whereas the others remain fully transparent across the solar spectrum. Linking level, expressed as gel content, was up to 80% for the EVA, up to 70% at POE-A, up to 75% at POE-B, and 55-85% at POE-C. The lamination of all minimodules was carried out using a two-chamber, two-stage thermal process.

Module performance was measured before and after 1,000 hours of damp heat (DH) using a commercial flash tester at 85 C and 85% relative humidity to study humidity-induced failures.

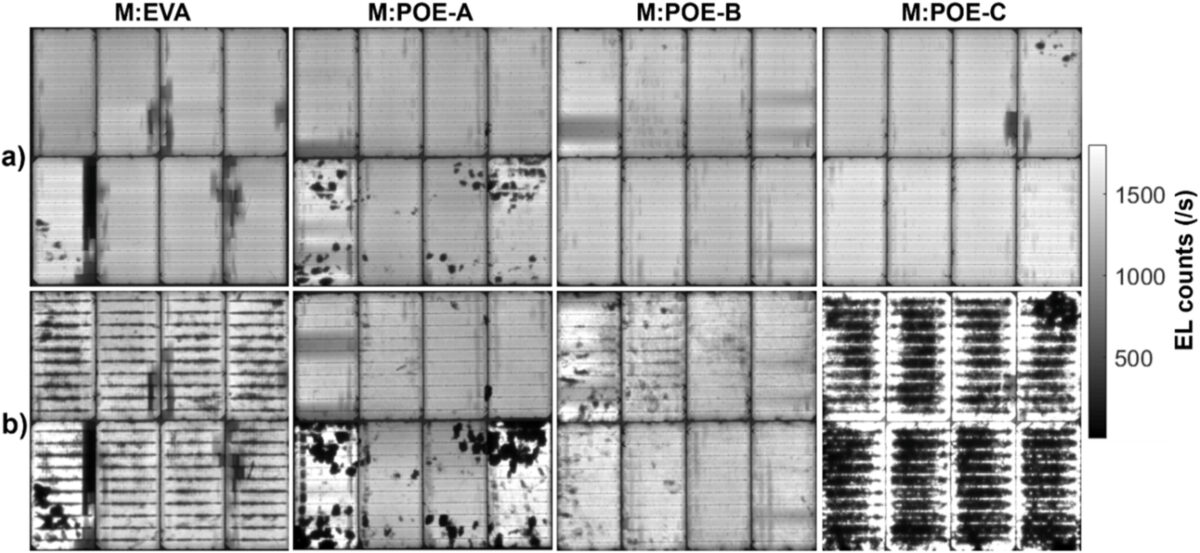

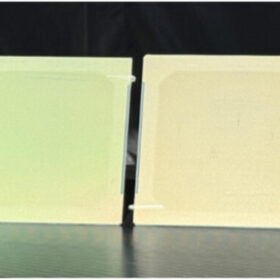

“The biggest surprise was that one POE encapsulant, which should have been the safe choice compared with standard EVA, actually performed far worse: in our damp‑heat test, the EVA module lost about 11% of its power, while the POE‑C module lost roughly 55%,” Sen said.

In compression, POE-A and POE-B showed reductions of 15.6% and 6%, respectively, and did not produce measurable amounts of organic acids.

“An equally surprising result was the role of the UV absorber in the encapsulant. This additive is normally included to protect UV‑sensitive solar cells and polymer backsheets from sunlight, but in this POE-C it appears to break down under heat and moisture, generating additional organic acids that join the corrosive cocktail attacking the metal contacts,” Sen said. “In other words, a chemical that is meant to protect the module can, under the wrong conditions, actually help to trigger premature failure.”

Sen’s team added that a multi-technique analysis of the POE-C minimodule suggests a potential cascade of mutually reinforcing degradation pathways. That included a thermo-oxidative degradation of the POE matrix, producing carboxylic acids; retained azelaic acid from soldering flux; and a hydrolytic breakdown of benzophenone UV absorbers into benzoic and phenolic acids.

“We are currently working on follow-up research, in which we will deliberately vary only one additive at a time, so we can pin down exactly which chemical ingredients make a module robust and which ones trigger corrosion in TOPCon and other advanced cell technologies,” Sen said. “The long‑term goal is to turn our current negative findings into clear design rules and quality‑control tools that keep future PV modules reliable for decades.”

The research work appeared in “The dark side of certain POE encapsulant: Chemical pathways to metallisation corrosion in TOPCon modules,” published in Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells. Researchers from Germany’s Fraunhofer Center for Silicon Photovoltaics (CSP) and Anhalt University of Applied Sciences have also participated in the research.

Other research by UNSW showed the impact of soldering flux on TOPCon solar cell performance, degradation mechanisms of industrial TOPCon solar modules encapsulated with ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA) under accelerated damp-heat conditions, as well as the vulnerability of TOPCon solar cells to contact corrosion and three types of TOPCon solar module failures that were never detected in PERC panels.

Furthermore, UNSW scientists investigated sodium-induced degradation of TOPCon solar cells under damp-heat exposure, the role of ‘hidden contaminants’ in the degradation of both TOPCon and heterojunction devices, and the impact of electron irradiation on PERC, TOPCon solar cell performance.

More recently, another UNSW rsearch team developed an experimentally validated model linking UV-induced degradation in TOPCon solar cells to hydrogen transport, charge trapping, and permanent structural changes in the passivation stack.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.