Faced with a complex problem, policy makers often turn to specialists who simulate the future using their assumptions of costs and investments and their characterisation of the power system and market. This sort of thing has a dismal track record in predicting prices and is susceptible to the perception, even if not the reality, that she who pays the piper picks the tune.

An alternative is a data-driven regression that analyses large quantities of historic market data to understand the factors that have driven energy prices in the past. This approach requires few assumptions, and the quality and predictive power of the model is objectively measured. Even if the future is uncertain, we might be able to get a better sense of it by looking carefully at the past.

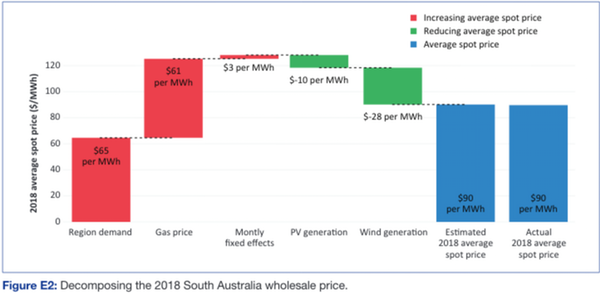

My colleagues and I used this approach to analyse South Australia’s wholesale prices from July 2012 to July 2018, during which period the annual average wholesale price increased by more than 30%.

There are many potential explanations for this increase: the last coal-fired power station closed in South Australia and two coal-fired power stations closed in Victoria; a greenhouse gas emissions tax came and went; electricity generation from the wind and sun increased by around 70%; while the price of gas climbed by a similar amount.

However, our research found by far the biggest reason for higher wholesale electricity prices in South Australia is higher gas prices. It does not help that so much of South Australia’s gas-fired electricity generation is remarkably inefficient.

Displacing expensive gas that is inefficiently used with cheaper sources of electricity can be expected to reduce wholesale prices. And so it does. In fact we found that in 2018, wind and solar generation in South Australia reduced prices by A$38 per megawatt-hour from what they otherwise would have been. Consumers were charged A$11 per MWh to subsidise this production, suggesting the subsidy paid for itself more than three times over.

Yes, with the rise of variable renewable production in South Australia, spot market electricity prices are more variable in 2018 than 2013. But there is no evidence that the power system, properly operated, can’t cope with it. Indeed, prices have been far more volatile in the past, long before the wind and sun became significant sources of power in South Australia.

In the market, prices are providing incentives for the development of storage and its substitutes and market participants are responding to these signals with investment in batteries and their substitutes and complements.

We also considered whether customers would have been better off if the state government had stepped in to extend the life of the Northern coal fired power station. Northern’s closure in 2016 raised wholesale prices by A$13 per MWh, but by 2018 all of this was offset by price reductions attributable to higher production from the wind and sun.

If the government had stepped in to keep Northern operating, customers and/or taxpayers would have been charged for the foregone emission reductions needed to ensure that Australia meets its Paris Agreement commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Even before counting the public money needed to revive the plant and mine, Australians would have been worse off. We are now extending our research and expect to reach similar conclusions on coal generation closure and renewable subsidies in other parts of Australia.

Chief Scientist Alan Finkel’s excellent energy policy review popularised the concept of an energy “tri-lemma”, suggesting that electricity policy needed to address trade-offs between prices, reliability, and emissions reductions.

But our research finds, emphatically, that renewable electricity generation brought prices down from what they otherwise would have been – and is likely to continue to do so. In electricity there is no dilemma between decarbonisation and lower wholesale prices.

System reliability and security must be prioritised in the transition to cleaner sources of power. But whether there is a dilemma between reliability and a cleaner power system remains to be seen.

The “tri-lemma” concept is already past its prime. Policy makers of all persuasions need to reflect this in their thinking.

This article was originally published in The Conversation. It is republished with permission.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.