pv magazine: Energy retailers must pay a shortfall charge of $65 for each large-scale generation certificates (LGC) not surrendered, however although prices have plummeted to $40, they still choose to carry forward even 100 % of their obligations, like Alinta did this year. How does that pay off for them?

Tristan Edis: Provided the retailer surrenders additional LGCs within three years of paying the shortfall to make up for their shortfall then they can get any penalties paid refunded in full, plus they must also fully comply for the most recent generation year in which they are seeking to get refunds.

So, what’s an example of this?

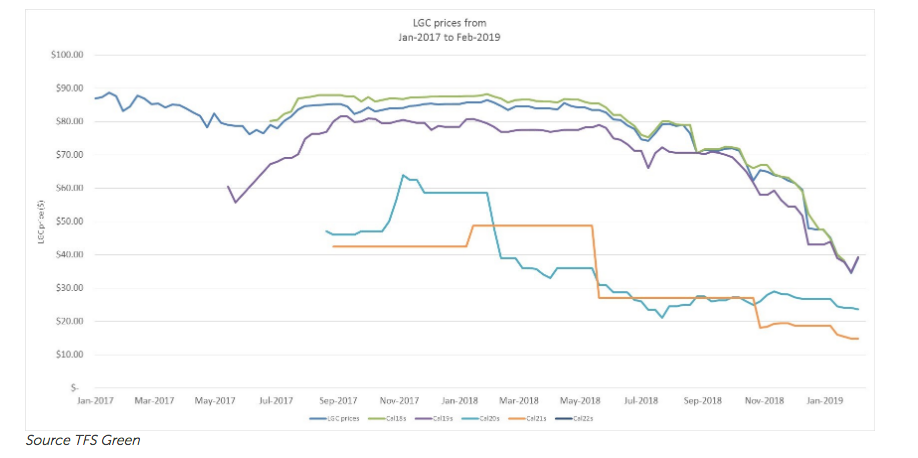

Let’s say the cost of an LGC to comply for 2018 generation year was $40 or alternatively the value of selling an LGCs you already hold, rather than using it for compliance. However, in slightly less than three years time you think you can buy up LGCs for $20. You then chose to pay the penalty incurring a cost of $65, but this $65 is not lost forever – it is just in essence like leaving it in a bank that doesn’t pay interest. In about three years time you then buy up extra LGCs for $20 and hand these extra LGCs over to the regulator who refunds you $65. You’ve therefore saved yourself $20 – compared to paying $40 if you’d fully complied back in February 2019 for the 2018 generation year.

From the perspective of energy retailers, is there a downside to carrying obligations forward?

There is a cost for saving this $20 – which is that you could have instead earned interest for three years on the $65 penalty you deposited with the regulator. At current three year bank deposit rates the interest rate is 2.8%. So the forgone interest over three years would be under $5. Overall you’ll be $15 better off by paying the penalty. That’s a simplified picture because many retailers will believe they could have invested that $65 in something that earns a better return than 2.8% but this helps illustrate the financial incentives at work.

Photo: pv magazine/Dave Tacon

How does that stack up against the timely surrender for the previous year?

In the end though the payoff would have been greater because many retailers that didn’t comply would have sold the LGCs they held for more than the LGC spot price in January. LGCs were $70 or more up until September 2018. There’s no way the big retailers could have done all their buying and selling as late as January 2019 because this would leave insufficient time to get themselves organised for the surrender compliance period in February. Instead most of the trading would have taken place well before prices had dropped to $40.

So the savings will be vastly greater – provided of course that policy doesn’t change in such a way that might inflate the value of LGCs in 2020 or 2021. This is probably unlikely but can’t completely be dismissed.

How would such a scenario unfold?

Labor may find itself unable to pass a National Energy Guarantee-like policy through the parliament, which might then lead them to instead try to increase the existing Renewable Energy Target to say 50%. This may be more acceptable to some future Senate cross benchers than a NEG-like scheme that can be more readily labelled as an emissions trading scheme. For example Clive Palmer’s United Australia Party, which currently has one senator, blocked the Abbott Government from abolishing or cutting the RET but they were very happy to help him abolish the Emissions Trading Scheme. If that kind of scenario unfolded then the gain to these non-complying retailers could possibly evaporate.

Why are the customers still paying the old RET costs (based on higher LGCs prices) through their electricity bills?

I suspect that large industrial and commercial customers will not necessarily be paying the old RET costs as many have contract clauses that allow them to source the LGCs themselves. Indeed I’ve been told that some of the big customers actually insisted that their retailer undertake a strategy of paying penalty and then making good later in order to take advantage of lower costs over a three year period.

For the small customers there is an argument that you have to take the good with the bad. You get prices locked in for a year and then if costs go up for the retailer then they don’t pass them onto you, but likewise if they go down the retailer gets to pocket the saving.

Although I would point out that retailers probably should be passing on the saving in the Greenpower premium – a premium you can pay to get power from renewable sources over and above the RET mandated amount – which is often a discretionary price element that is not fixed. I haven’t seen this occur with my own retailer but not sure about others.

What does such a precipitous fall in the LGCs value mean for merchant projects?

For existing merchant projects the precipitous fall in the LGC price is certainly not good thing but for many it will have been expected – you’ll notice that a significant number of projects that started off merchant have since been contracting much of their capacity over 2018. It’s just the fall may have come a year or two earlier than some may have expected, at least when they committed to the project.

For those who committed to projects prior to mid-2017 there was generally a belief – including by myself I have to admit – that the market wouldn’t get close to supplying enough LGCs to meet the 33,000 GWh target by 2020 and we’d have a shortage until as late as 2022. However, the scale and speed of project commitments that have occurred has been quite incredible and as time has gone on it has become increasingly more likely that the price collapse would come sooner. Still trying to pick the exact time of the collapse was not obvious because it depended on the attitudes of senior executives and board members of big retailers to the possible shame of failing to comply with the Renewable Energy Target.

I think if you asked around market participants at the start of 2018 whether they thought a government-owned retailer that sought to brand itself as 100% renewable and clean and green would deliberately not comply with the renewable energy target, most would have said no. If the environmental groups saw this as a priority issue then it could have noticeably damaged the brand image of Snowy Hydro’s retail brands – RED Energy and Lumo. But with a federal election coming in May and investment in renewables very strong the environmental groups have bigger fish to fry.

A number of merchant projects have already calculated with a drop in the LGC value, but what has happened with wholesale electricity prices in the meantime?

Counteracting this collapse in LGC prices for merchant projects has been that wholesale power prices have remained higher for longer than the market had generally expected. The high prices for 2019 are particularly surprising but due to poor rains Snowy Hydro’s storages have run very low and they’ve upped their prices to conserve water – this has then helped keep power prices up in spite of lots of supply that will come online this year.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.