From the October edition of pv magazine

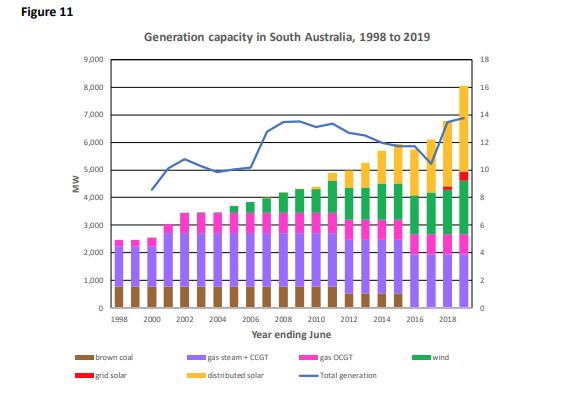

Very few grids in the world have decarbonized as rapidly as South Australia. The state’s emissions intensity has fallen from over 700 kg/MWh in 2008 to less than half that in 2018. According to a report by The Australia Institute (TAI), for nine of the 18 months until September, half of all electricity supplied in the state has been from solar and wind generators.

Long road

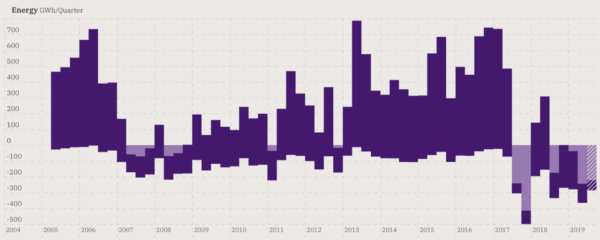

For many years, the state had been a net importer of energy and local electricity generation, mainly due to resource constraints. According to data from the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO), the state had the highest average wholesale prices among the mainland National Electricity Market (NEM) regions in 17 of the last 20 years (graph from OpenNEM). On top of that, the state’s wind and solar resources are among the nation’s best. “Very significantly, the federal Renewable Energy Target was designed without geographical limitations, so [the state] … was able to attract more than its “fair share” of renewables,” says Simon Holmes à Court, senior adviser to the Energy Transition Hub at Melbourne University.

This is somewhat ironic given that the federal coalition government has often berated the state for its rapid adoption of renewables. At the state level, the political climate is much more favorable. “A stable, pro-development Labor government worked hard to remove red tape and bring developers to the state,“ Holmes à Court says. “The relatively recently elected Liberal government has a progressive energy agenda and a non-ideological and pragmatic energy minister has kept the state on pretty much the same course set by its predecessor.”

All eyes on SA

As a testbed for future scenarios of high renewables penetration, South Australia is under the close watch of AEMO. While it continues to intervene by directing gas generators to run or ordering wind farms to curtail output, AEMO has acknowledged that – as it gains more experience – it feels it can ease back such interventions.

With around 1 GW of small-scale PV on the state grid, the time of minimum demand has shifted from the early morning to the middle of the day. This represents a novelty presently limited to South Australia, while for other NEM regions, the overnight period remains the lowest demand part of the day. “It may not be long before we see short periods with zero grid demand due to rooftop solar,” says Holmes à Court. “As such, [the state’s] connectivity to the other NEM markets, for exports, will be increasingly important.”

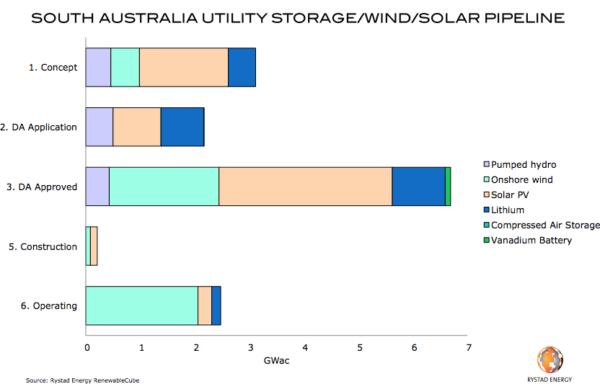

The state is already looking at two interconnectors to Victoria and another one to New South Wales. Some projects are already lining up in expectation of grid upgrades, such as Neoen’s Goyder South project, featuring 1.2 GW of wind, 600 MW of solar and 900 MW of battery storage. However, everything strongly depends on the South Australia-New South Wales interconnector (not included in Rystad Energy’s graph below).

“There is no doubt the … interconnector would be critical for the development of several projects as it effectively doubles the export capacity of [South Australia],” says David Dixon, senior analyst for renewables research at Rystad Energy.

He lists the upsides for the state’s solar pipeline: There are very few developed big PV projects, with just the 220 MW Bungala and 95 MW Tailem Bend projects operating at present. But the state is geographically to the west, meaning such solar farms still generate during the peak periods on the east coast. Marginal loss factors are also better for PV farms, relative to other states.

With or without you

With or without grid upgrades, virtual power plants (VPPs), mega-batteries, pumped hydro and synchronous condensers will all help facilitate more renewables in South Australia. The state is already home to the world’s largest operating battery – the 100 MW/129 MWh Hornsdale Power Reserve. The Tesla big battery saved almost AUD 40 million in grid costs in the first year of operation, but perhaps most significantly, it has raised the profile of energy storage and demonstrated its capabilities.

“So long as the cost of gas remains high, and especially as the cost of renewables and storage keep falling, we’ll see more renewables entering the grid in [South Australia] – regardless of whether the third interconnector is built,” Holmes à Court says. In addition to several pumped hydro proposals and a few sizable VPPs in the making, the state is also in line to roll out synchronous condensers by local transmission company ElectraNet. In a major announcement that has cast a long shadow over South Australia’s gas fleet, the poles-and-wires company identified syncons as a cheaper alternative to gas for system security.

However, syncon also plays the bad guy. In the wake of the 2016 black system event, South Australia’s Office of the Technical Regulator added new requirements for minimum levels of inertia and/or fast-frequency response for all new renewable generators. This adds costs to new projects. According to Rystad Energy’s Dixon, there are a few more challenges for big PV projects in the state. In addition to limited transmission export capacity, these include competition from the high penetration of rooftop PV, an inability to get PPAs to secure financing, and spot price variability.

While negative daytime prices are becoming increasingly frequent amid a flood of generation from solar and wind, a rush in development approvals, dominated by big PV and megabatteries, sends a clear signal that the state will take even bolder steps towards its 2030 target of “net” 100% renewables. “I once asked a South Australian bureaucrat why the state had such a positive attitude to renewable energy – he said ‘never get between a South Australian and a development dollar’,”says Holmes à Court.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

1 comment

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.