Australia’s thinking on climate change and energy transition must forever be informed by the inferno of this summer 2019-20.

A Stanford University update of research on transition to 100% renewable energy — which provided the basis for the energy component of the US Green New Deal — was published in the journal One Earth a few days before Christmas 2019, and extends its transition modelling to 143 countries, including Australia and New Zealand.

The Green New Deal (inspired by President Roosevelt’s New Deal of social and economic reforms addressing the effects of the Great Depression) is a resolution introduced to the US Congress by two democratic senators, which presents a plan for tackling climate change through cross-sector electrification and economic transformation. In early 2019 the New York Times described the Green New Deal as likely to “remain a lightning rod throughout the 2020 presidential campaign”.

By late 2019, the EU Commission had trumped the US by adopting its own 50-policy Green New Deal strategy, including the legally binding target of reducing EU emissions to net zero by 2050.

Lead author of Impacts of Green New Deal Energy Plans on Grid Stability, Costs, Jobs, Health and Climate in 143 Countries, Mark Z. Jacobson, says his team published the updated report to “quantify” what transition requires, and to “give countries guidance”.

“To be honest,” he said, “many policymakers and advocates supporting and promoting the Green New Deal don’t have a good idea of the details of what the actual system looks like or what the impact of a transition is… This work can help fill that void.”

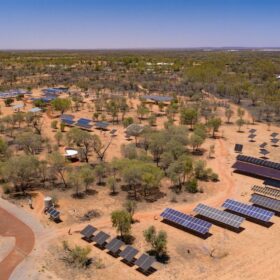

As roads around Australia are closed due to the risk of firestorms crossing and the post-conflagration hazards of smouldering forests falling, the Stanford “roadmap”, as it is described, offers a science-backed plan for developing wind, water and solar (WWS) infrastructure, and calculates the outcomes of eradicating reliance on globe-warming fossil fuels by the year 2050.

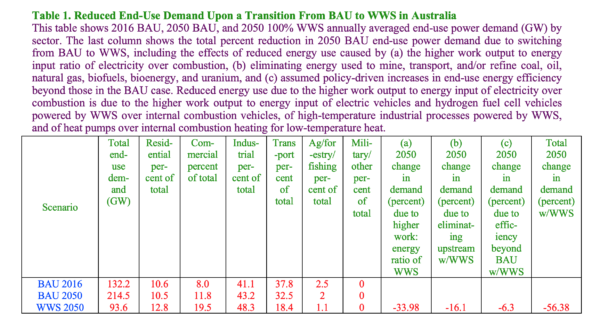

The country summary for Australia — Impacts of Green-New-Deal Energy Plans on Grid Stability, Costs, Jobs, Health, and Climate in Australia — contrasts the end-use energy demand of the Australian economy under a business as usual (BAU) scenario, with those in the WWS future, predicting a 56.38 GW reduction in 2050 energy demand if Australia electrifies all sectors see Table 1 below.

Electrifying revelations

In a 2017 video on the energy-transition timeline to renewably sourced electricity for countries around the world, Jacobson, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at Stanford, and the co-founder of the Solutions Project — a US not-for-profit organisation that works to educate policymakers and the public about transition to 100% clean, renewable energy — explained the massive expected reduction in energy demand when all sectors of the economy are electrified.

Worldwide, he anticipates the switch to electricity to result in a 42% reduction in energy demand and attributes 23%, the largest part of that reduction, to the greater efficiency of electricity over combustion: “For example,” Jacobson says, “in an electric car, 80-86% of the electricity going into the car goes to move the car — the rest is waste heat. For a gasoline car, only 17-20% of the energy in the gasoline goes to move the car — the rest is waste heat. So the end-use power demand actually decreases by a factor of 4 or 5 in most transportation types.”

Jacobson says a further 12.6% of all energy demand worldwide is used to mine, refine and transport fossil fuels. Therefore, in a WWS scenario, he deduces, “because the wind comes right to the turbines, the solar comes right to the panels … we don’t need to mine, refine or transport fossil fuels”, so that’s 12.6% of worldwide demand dissolved.

Another 7% reduction will come from focusing on energy efficiency measures, such as better-insulated buildings and demand management. Such reductions in demand will reduce infrastructure required to meet the world’s energy needs.

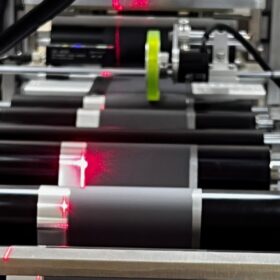

Pumping up renewable-energy volume

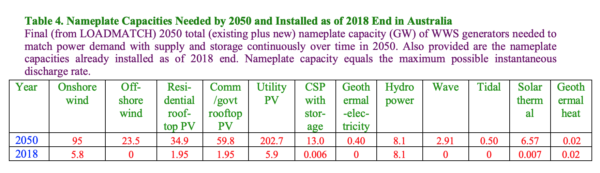

The Stanford team’s roadmap for Australia in 2050 distributes the country’s needs according to the nameplate capacities below, with the majority provided by solar generation (residential rooftop, 34.9 GW; commercial rooftop, 59.8 GW; and utility scale, 202.7 GW).

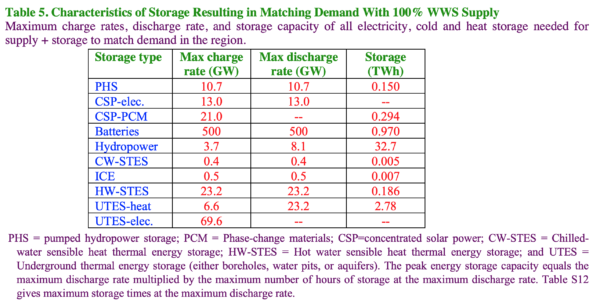

The storage technologies needed to match demand in a WWS-powered Australia might be provided as shown in Table 5:

Billboards along the Stanford-envisaged highway to Australian electrification include elimination of Australian energy emissions contributing to global warming; a reduction of 62% in private energy costs, from US$194 billion per annum, to US$74 billion/annum; and 342,000 more full-time jobs in construction and operation than will be lost in fossil-fuel-related industries.

As Australians choke on the haze of millions of hectares razed, the Green New Deal also promises to save 3,000 Australian lives currently sacrificed to air pollution per annum — that’s in a non-catastrophic-bushfire year.

Jacobson’s team has estimated the cost of a Green New Deal for Australia at US$820 billion.

The incalculable future costs of business as usual

In calling for Australia to establish a National Climate Disaster Fund by levying fossil fuel producers $1 per tonne of embodied emissions, The Australia Institute (TAI) last week pointed out that, “The catastrophic Black Saturday bushfires in Victoria in 2009 lasted a single day and are estimated to have cost over $7 billion.”

As yet there is no end in sight for the inferno of Summer 2019-20, but the toll of lives, homes, livelihoods, wildlife and infrastructure lost is already many times higher than those of Black Saturday.

Richie Merzian, TAI’s Climate & Energy Program Director, says that everyday Australians and businesses are currently paying for the impacts of climate change exacerbated by fossil fuel production: “Every tonne of coal or gas mined in Australia adds approximately 2.5 tonnes of heat trapping gas to the atmosphere, making bushfires more frequent and more intense.”

While the costs of natural disasters escalate under a business-as-usual, global-warming scenario, the estimated US$820 billion upfront investment by Australia in further renewable-energy infrastructure (generation, transmission, storage, distribution), would pay for itself over time in energy sales, calculates the Stanford report.

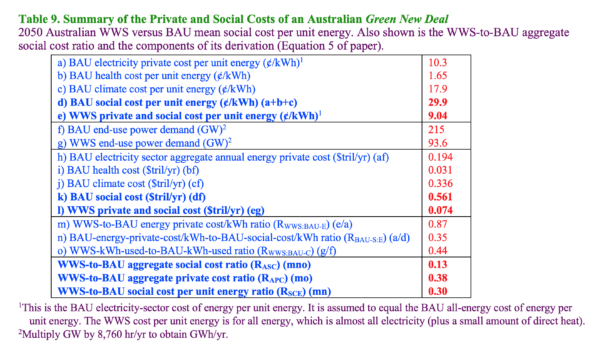

And the private and social costs of energy would be massively reduced, it suggests in Table 9 of the Australian summary.

Jacobson emphasises that the Green New Deal as laid out for Australia and individually for other countries simply demonstrates the possible. “There are many solutions and many scenarios that could work,” he says.

What greater catalyst is needed for a planned transition?

In this transformative year, more scientifically calculated inputs and outcomes are welcome. Those that link Australia with international efforts, resolutions and legislation, even more so.

The Australian Federal Government has refused to acknowledge Australia’s exposure to the effects of climate change. It has argued the country’s insignificance in terms of global emissions as justification for not developing a climate-action plan that transitions Australia from reliance on fossil fuels towards its abundant renewable resources.

In a report on Australia’s scorched New Year’s Eve, Deutsche Welle, the German global news broadcaster, quoted outspoken economist Steve Keen on the psychology of the Australian Government’s lack of leadership on climate change. Together with the heartbreaking reports of devastation, the human and economic costs of this summer, what he said should provoke a revolution:

“Australia is politically dominated by climate change trivialisers … they’ve always assumed that sea level rise would be the symptom, and Pacific island nations, who don’t matter, the victims. Now with the bushfires, the populace is realising that Australia may be the first victim.”

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

“The Green New Deal (inspired by President Roosevelt’s New Deal of social and economic reforms addressing the effects of the Great Depression) is a resolution introduced to the US Congress by two democratic senators, which presents a plan for tackling climate change through cross-sector electrification and economic transformation. In early 2019 the New York Times described the Green New Deal as likely to “remain a lightning rod throughout the 2020 presidential campaign”.”

Please, let’s don’t loose track of what Roosevelt’s New Deal was for. Putting people back to work after the depression and stock market crash blow back from 1929. The infrastructure programs helped employ and grow the country’s economy. Now the U.S. is once again challenged by the degradation and failure to keep up and enhance this infrastructure. This ‘cost’ of maintenance and repair has fallen by the way side to “pork” programs that create egregious “bridges to nowhere” and air ports that were never used but cost millions to construct.

““Australia is politically dominated by climate change trivialisers … they’ve always assumed that sea level rise would be the symptom, and Pacific island nations, who don’t matter, the victims. Now with the bushfires, the populace is realising that Australia may be the first victim.””

To me the Australian people call to mind Psalm 20:8

“They are brought to their knees and fall, but we rise up and stand firm.”

The individual can stand firm and install their own solar PV and energy storage. Vote out one Government for a new one and still “stand firm” and use the technologies available to take responsibility for their own energy use every day.

All of these institutions of “higher education”, Stanford University is another elitist conclave without consequence provider. Just how many of those “professors” that make well over $150K a year and have pensions set for life on the backs of the public at large, actually spent some of that “paycheck” and installed solar PV, solar hot water, wind, micro-hydro, fuel cell power on their homes? All the while, it seems the people of Australia have been installing more personal solar PV and energy storage per capita than many more populace countries of the World.