From the August edition of pv magazine global

Australian residential battery storage installations have been difficult to both track and forecast. Since 2017, when households and small businesses in the country began installing significant volumes of distributed battery systems, a wide range of annual installation data has caused some confusion – and forecasts have varied wildly.

Not helping matters is that a national registry for distributed battery storage units is not mandatory. The Clean Energy Regulator manages a voluntary program, but some analysts say that it is likely only capturing one-third to half of small-scale battery installations. By contrast, the vast majority of rooftop solar arrays are registered by the Clean Energy Regulator, by virtue of the generous Small-scale Renewable Energy Scheme (SRES) – providing detailed state-by-state updates to the rooftop PV segment on a monthly basis.

In 2016, analysis from Morgan Stanley was perhaps the most optimistic regarding distributed storage Down Under, and the market has massively underperformed on these expectations. The Morgan Stanley analysis published a mid-range scenario, which would have seen around 1 million battery storage systems installed by 2020. Its optimistic scenario envisaged roughly double that, or one in five homes.

In contrast to these forecasts, today, IHS Markit puts cumulative installations at approximately 82,000 units in 2020, representing well over one in 100 Australian homes – a far cry from the Morgan Stanley optimism. Local Australian consultancy Sunwiz puts the cumulative figure even lower, at 73,000.

Leading market

Leading market

While this installation rate may not have met some previously towering expectations, the result still places Australia at equal third/fourth position with the United States, behind Germany and Japan, respectively, according to IHS Markit data. However, the analysts note that this is based on the number of systems installed rather than capacity, with U.S. residential system sizes tending to be considerably larger.

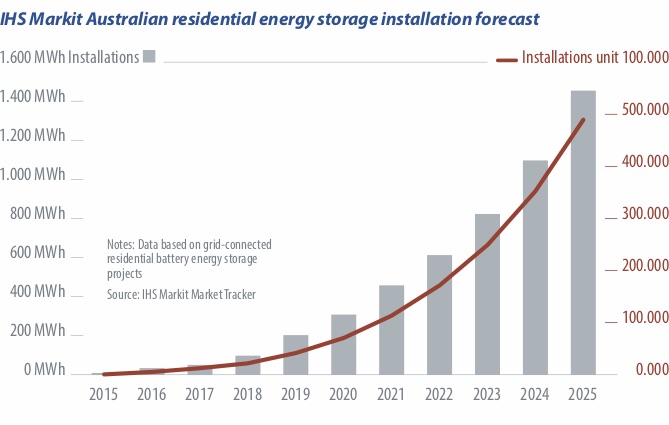

To assemble its data, IHS completes a quarterly survey of “major system” suppliers, which it correlates against shipment data. It is published in its IHS Markit Residential Storage Index. “In 2018, we saw 12,000 systems installed … that equated to about 99 MWh,” explains analyst Mike Longson, who works on the index alongside Julian Jansen, head of energy research at IHS Markit. “That then increased to 22,000 in 2019, which was 204 MWh.”

“We are definitely quite bullish in terms of the future forecast,” adds Jansen. But others have expressed similar sentiments about the market’s development, only for those expectations to go unmet. The main reason behind this underperformance is likely that battery installed prices have remained stubbornly high – and many Australian consumers are not as motivated by lifestyle, status, or environmental reasons as they may be in the United States.

Even under aggressive assumptions for the price reductions in residential storage over the coming years, in most cases coupling a battery to a rooftop system will extend the payback period of the system. While a rooftop solar system can quickly become cash positive for the homeowner, in most Aussie homes using the electrons generated on the rooftop in the home – via a battery, simply doesn’t pay.

In fact, many modeled installation paybacks for a residential battery storage system are beyond 10 years – pushing it out beyond the time at which the battery will have to be replaced. “There’s only a limited number of eager early adopters willing to spend money on a home battery that’s unlikely to pay for itself,” argued Ronald Brakels, a blogger at lead generator SolarQuotes. “Every time one’s bought, this tiny market shrinks a little more.”

This phenomenon, an exhaustion of the “early adopter” households willing to invest in an uneconomic battery, is the cause of the market plateauing in 2018-19, argues Brakels, drawing on the Sunwiz installation figures (see table below). However, the IHS Markit figures tell a different story, with lower installation rates in 2018 tracked when compared with those of Sunwiz, but a near doubling of the market in 2019. The IHS team expects some 54,000 batteries to be connected by the end of this year, at roughly 311 MWh of capacity. According to this forecast, there is little sign of market exhaustion in sight.

| Sunwiz: Annual residential battery installations | |

| Pre-2016 | 2,500 |

| 2016 | 7,325 |

| 2017 | 17,839 |

| 2018 | 22,671 |

| 2019 | 22,661 |

| Source: Sunwiz | |

Residential drivers

There are emerging market dynamics that are also lending credence to forecasts of rapid residential storage market expansion. Virtual power plant (VPP) schemes in South Australia and New South Wales are likely to generate additional revenue streams for distributed battery owners. The skeptical Brakels notes that VPPs may play a role in improving battery paybacks, but adds that programs are only in their early stages, so they probably will not improve system paybacks in the short-term. “It’s just a matter of when. And 2020 is not when,” Brakels says.

In terms of driving demand, there are a number of developments that appear promising: backup power provision and Australia’s rapidly changing distribution network. “With the bushfires that we saw in the last Australian summer, we definitely saw sentiment from consumers who could afford it … installing a battery alongside solar creates a strong driver for those customers facing regular outages,” says IHS’ Jansen.

With summer temperature records being surpassed on close to an annual basis now, the security of electricity supply during very hot periods is becoming increasingly difficult for grid operators and state governments to deliver. Facing sporadic brownouts or blackouts when temperatures soar above 40°C, the ability to keep the air-conditioning running and the beer fridge cold is a value proposition beyond paybacks.

Another longer-term market dynamic on the demand side looks likely to set the stage for residential battery uptake: ever-increasing penetration rates of rooftop solar throughout Australia’s suburbs. That rooftop solar is popular among homeowners is no surprise, but the accelerating rate of uptake is pretty astounding.

Cornwall Insights Australia published a note in July that, despite a market downturn due to Covid-19 lockdowns, Australia is likely to have installed some 24.45 GW of rooftop PV through to 2030. What’s particularly notable is that the Cornwall forecast is based on average system sizes of 4.5 kWp, while in reality average system sizes are fast heading up to 6 kWp. “If you take six [kWp] then we’re looking at 29 GW [by 2030] just on the solar PV side of things,” says Cornwall Insight Australia consultant Ben Cerini.

This massive fleet of sub-100 kW PV systems, the system size covered by the SRES program, is beyond what the Australian Electricity Market Operator (AEMO) is anticipating, even under its most optimistic scenarios for the segment. AEMO was working with a rooftop PV number of 21 GW by 2030 in modeling it produced in 2019, upgrading it to 23-24 GW only six months later.

Distribution markets

“Part of our reasoning for showing this is that all the estimates that the market is working with continue to underestimate just how much DER [distributed energy resources] is coming onto the network,” says Cerini. He argues that efforts to develop market structures at the distribution level of the electricity network should be accelerated. “We don’t want to be creating markets for the sake of it – they should be designed for people to pay less and be accurately remunerated,” he continues. “In a high DER network, we need to look at these types of markets.”

Such types of market structures at the distribution network level could open up a range of revenue streams for batteries installed in Australian homes – from the provision of frequency regulation, ancillary services, and voltage control, down to the individual substation level.

Even if distribution markets prove too challenging to realize in the short term, it is appearing likely that limitations on grid export of PV electricity will be put in place, or fees introduced for the usage of the network to feed-in solar energy. Some privately owned distribution networks in Australia, most recently Powercor in Victoria, are making noise about having to introduce limitations on PV grid exports because of capacity constraints.

Given this potential outcome, the installation of a battery may become a “no brainer” for the homeowner. Utilities remain little loved, and the idea of having to pay to export homegrown solar electricity will likely provide a considerable push for storage. Already some DER subsidy programs, such as in New South Wales (NSW), are no longer being provided for “pure PV” arrays and only being applied to battery-only or solar+storage systems.

Alongside NSW, South Australia, Queensland and the Australian Capital Territory have active subsidy programs for residential storage. These subsidies, which may still not bring financial paybacks below 10 years in all cases, have built confidence in residential batteries, among both installers and homeowners, says John Grimes, CEO of the Smart Energy Council.

“People have that longitudinal experience with the technology, which is now 2-3 years in some places,” says Grimes. “The installer base is getting confident. And then prices are coming down, changing the economics, putting it into the ‘worth having a look at’ category.”

| Leading distributed storage providers 2019 (alphabetical order) | |

| Company | Headquarters |

| Alpha ESS | China |

| BYD | China |

| LG Chem | Korea |

| sonnen | Germany |

| Tesla | United States |

| Source: IHS Markit/pv magazine | |

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

2 comments

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.