pv magazine Australia: Australia is the testing ground for a lot of different aspects of the future green hydrogen market. And one of the experiments we’re seeing between the various projects is the economics of solar and wind versus solar and storage for hydrogen production. So why is EEW going the solar plus storage route in its Gladstone Project?

Svante Kumlin, CEO Eco Energy World: You’re right, we’re planning substantial storage in our project. So we charge at peak and during the night as well. But you need a lot of battery, and it depends how long you run the hydrogen plant. But we will have at least 100 MW of storage in this plant. We might go bigger. And we can, as you say, use some other resource such as wind via a PPA during the night to run the plant and charge the battery.

And is your plan to produce green hydrogen for export or convert it first to ammonia or some similarly transportable product?

SK: Yes, we initially plan to produce green hydrogen for export. As we see the export market take-off, especially in Japan, conversion really depends on the means of transport. As you say, conversion to ammonia is one method but hydrogen can also be compressed or liquified.

And how will you transport the green hydrogen from Queensland to Japan?

SK: Transporting hydrogen is difficult, but that’s why the project is located where it is, because the product needs to be shipped north. Gladstone Port is one of these ports in Australia identified to be ideal for these kinds of exports. And of course there are other players there too, Sumitomo for example although they’re not completely green. But personally I also hope the Australian domestic market will develop a demand for green hydrogen locally. I think it would make a lot of sense but it’s not there now. But what I see as a really big market going forward is on heavy transport, fuel cells. And I also see a market in the mining industry where gensets and backup solutions are expensive and dirty. There is quite a bit of interest in converting all that power into hydrogen solutions, and it is just a matter of how quickly that is going to happen. Today, the market in Australia is for export but I do believe the local market will develop and we are seeing a lot of interest.

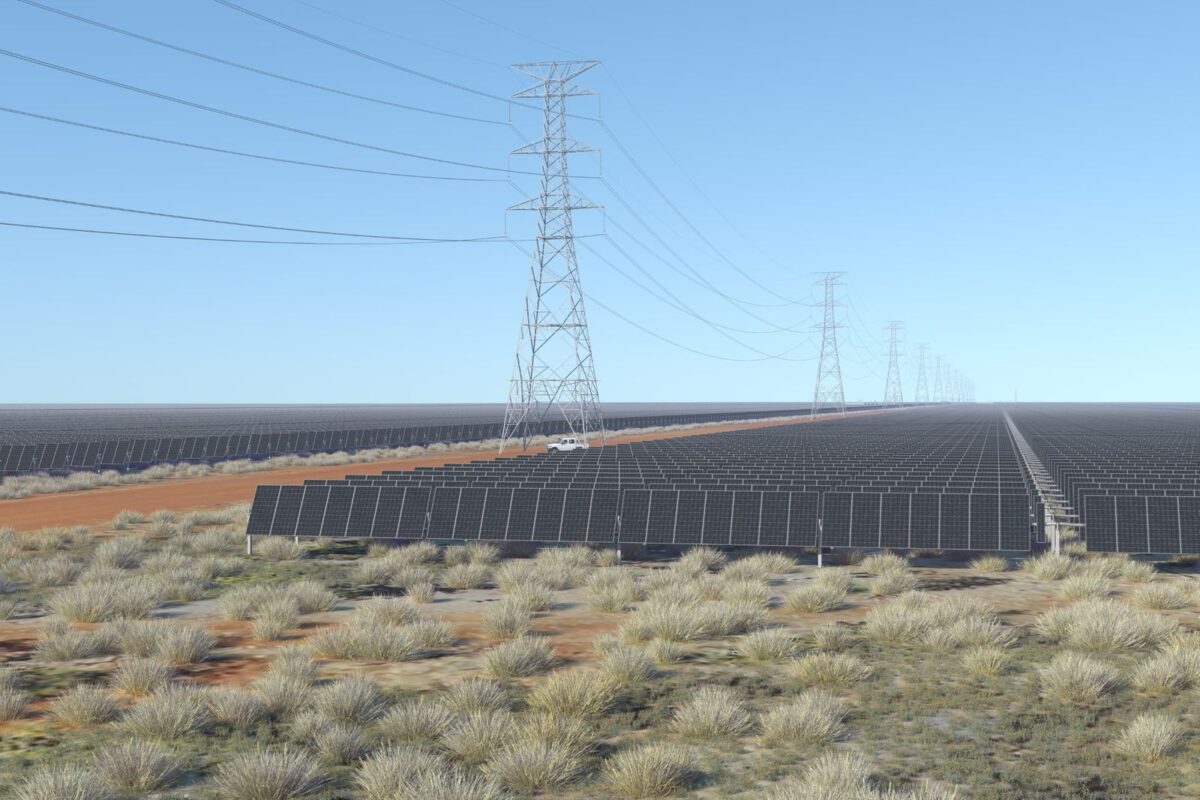

Image: EEW

We certainly have the solutions, for instance, for the mining industry, it’s just whether the industry is able to pool together to develop the kind of infrastructure necessary for decarbonisation.

SK: There is quite a lot of interest from certain financing groups to actually go in and finance all these mining companies for the transition. We have been approached by some of them already. So, if you just have the hydrogen then you will see that taking place because it makes economic sense. When they can make money from it, or become greener without losing anything they’ll do it. But they won’t do it if they lose anything.

Well let’s move back to the export market. Transporting green hydrogen is still incredibly expensive, how can you economically transport green hydrogen to north Asia?

SK: Well, there are shipping solutions for it and we’re discussing with shipping companies. Of course, our project is planned to come into production in the last quarter of 2023. While at the moment the transport cost is the same as the cost of producing the hydrogen, we have a pricing outlook for 2024-2030 and that outlook shows us still hitting our marks despite the transport costs.

I’ve been in the solar business for 12-13 years. When I started 1 MW of solar had a CAPEX of €6 million, today the same megawatt is €400,000, and I believe that hydrogen will have a similar ride. In the beginning you have 20% decrease per year in the CAPEX, and then it levels out at 10%, but you will see dramatic falling of CAPEX. So we are seeing and targeting a hydrogen price for 2023 that is doable for export to Japan, otherwise there’s no business.

For the shipping solutions, I will say that sooner or later there will be more special tonnage built. And there is a lot of interest in that, not just from the buyers but also the shipping companies because they see that they have to convert. Indeed those latter companies themselves are big polluters so they have to provide these solutions by way of offsetting their own carbon as well.

By 2023-24 we believe the price will be between $4-5 per kilo in Japan. 2030 we’re looking more at $3. And I would say half of that is transport cost and half production. Meaning that by 2024 we will need to be producing green hydrogen at a price around $2.

And can this Gladstone project reach that price or will an additional power source through the night be necessary?

SK: Yes, you need to have a longer producer cycle, meaning you need storage and you probably need a PPA with a wind farm as well. Otherwise you can’t utilise the production capacity to get down to that price so you’re right on that. And we are looking into such PPAs which are quite useful because most people aren’t buying wind power during the night so the prices are cheaper.

The problem then is not the price during the night, the problem is getting it from the right source. I think it’s very feasible. And that’s why it’s very beneficial coming in from the solar side, because you know all about the structure of the business, especially in Queensland and all of our projects have been in Queensland.

And the Queensland Government are very keen to encourage hydrogen hubs such as Gladstone?

SK: Yes the Government has contacted us and I can’t tell you much about that but the logistics of using the stuff that we need, the port and the pipelines, are an ongoing discussion, but there is enormous will from the Government to make it happen. And I can understand that because the coal exports will soon suffer and need replacement. Hydrogen is a perfect solution and we are excited to be involved in that.

You mentioned the end of 2023 as a production date, could you give me a timeline of the solar aspect of the project?

SK: The solar project itself is fully authorised and ready to build. We would probably aim for construction in 2022 concurrently with the hydrogen plant. With a soft date of connection in early 2023. But actually, we have been considering not connecting the solar farm to the grid because the grid is expensive. But at the end of the day, because we need to import energy, we would lose a lot of our flexibility if we weren’t connected. It might be that we don’t connect for export only for import, but we don’t save so much money on that because the connection itself in Australia is very expensive.

And often in terms of EPCs and other aspects we have to wait for AEMO and you know it has been hard with that, like working against a wall. It has felt that we are at a disadvantage compared with the base-load operators. But the Australian dollar is a bit stronger, system prices are falling, things are improving and our plan is to close on an EPC before the end of Q2.

Would you say it has been the falling storage prices that have allowed you to break through some of those walls?

SK: Well there has been a lot of delays in terms of the grid for the development of the solar. And Australia is more costly than other parts of the world. So we’ve been taking a lot of risks without the security of connection, but the things we’ve gone through have strengthened our plan. I would say the main thing is that the political climate has meant a lot of uncertainty for renewable energy developers, and now that that climate seems as if it is changing then the guidelines given to the regulators and how they deal with it is also changing, and that is very important.

Take Europe as a parallel. If you develop renewable energy in Europe you get priority to export that energy to the grid before any dirty generators. In Australia it is the opposite. Renewable generators have to pay a lot of different charges for connection and that system I hope is slowly going to change. Everyone knows the coal generators are going to be phased out so what is the point of keeping them alive to profit instead of the new ones who need to take over?

It’s just a money question. But the tide is turning. And that is going to influence construction because a lot of EPCs have been going out of the market in Australia. Which is making our life more difficult because we have fewer to negotiate with and the prices go up, or at least don’t go down. And that is because the contractor’s price perceives the risk and the risk of grid delays and uncertainty has been high for a number of years.

I guess that can be demoralising when the biggest concern as a project developer in the green hydrogen space is not getting the energy, or demand, or transport, but grid uncertainty.

SK: I know, I know. That’s why hydrogen is a great thing, but still we have to connect because we need to import. Otherwise we could be off-grid.

Of course, in another way, since we are not planning on exporting much to the grid, and we only plan to import to the grid when there is too much energy, such as during the night, so the access to the grid for projects such as ours should be much easier than for a full grid-export solar power plant.

Why should you play by the same rules as someone exporting to the grid when you’re exporting to North Asia?

SK: Yes I think that is going to be the case. And I think it is also important to say that after building this first project we will keep building capacity because we have to. Because prices are going to be going down, and the next plant is a lower CAPEX. For instance, if you have a CAPEX of $1 million, and then $750,000, and then $500,000, but then the price of the hydrogen is falling as well. So we’re not announcing anything on that front yet but we will be looking to expand our production.

Where we are now we are 20km from the port, 20km from the pipeline, that is important. So we would look to expand in the Raglan area and maybe somewhere else in Australia. And I would say that by 2030 we’d be looking at having 1 GW of production facilities. That is our grand plan, but only this first project has been announced.

And could you talk a bit about financing for the project?

SK: On the financing side, the way we see the project being financing is by a blend of debt and equity. The R&D work might get a little bit of help, but we don’t’ want to rely on grants and things like that because you’ll end up getting delayed in order to write some report to someone or other in order to apply for funding. We’re not going to do that. I know a lot of Australian groups are doing that, they wouldn’t go ahead if they didn’t get the grants. We’re not going to do that. If we get grants for anything, great, but we’re not going to be hostage to that.

Time is of the essence.

SK: Yes, and our project is based on sound commercial facts. It doesn’t need to be subsidised because it’s not the way we do business. I believe that this first of our hydrogen projects will be funded with equity but perhaps traditional banks will help finance our second project. But it’s fair to say the equity component will be at least 50% on the hydrogen part. On the solar part it is not a problem because solar is very bankable.

And am I right in thinking you had the solar plant planned out first and have tagged idea for hydrogen came later?

SK: Yes, we started thinking about hydrogen in 2017. We thought hydrogen would be a great way of storing energy. But then you produce the hydrogen, store it somewhere, and then you put it into a fuel cell or a turbine and export it again. That was too expensive and you lose energy in all this. That’s how we started. But then the CAPEX prices of electrolysers and equipment started to come down, and it started to make more sense.

For us we see it as a great advantage coming from solar because electricity is the biggest cost factor. If you don’t have cheap energy it’s not going to work, and that’s what you have in Australia with solar during the day and wind underutilised during the night.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.