The Australian Energy Market Commission’s (AEMC) has framed its proposed two-way pricing reform, labelled a ‘sun tax’ by critics, as an issue of equity. The AEMC’s rule change would allow electricity distributors to charge homes with solar for exporting their renewable energy back into the grid. The thinking is that it costs networks money to integrate distributed rooftop solar into the grid as it inverts the normal flow of electrons, therefore solar homes should pay their ‘fair share’ to cover this loss. The premise that colours this reasoning is that it is usually wealthier Australians who are able to install solar, meaning the rich get the solar and the savings and leave poorer Australians to foot the bill. Hardly an equitable setup.

“Many interested parties would have common ground with this perspective, but the debate as it has been set out so far has got the evidence wrong by 180 degrees,” Victoria University’s Professor Bruce Mountain told pv magazine Australia. He’s authored a new paper for the Victorian Energy Policy Centre along with Kelly Burns, also from Victoria University, which claims that when data from rented and owned homes is divided, the relationship between wealth and solar “evaporates”.

“When you properly put it together it is evident that charging for network injections will hurt the poor, far more than it will hurt the rich,” Mountain said.

Gavin Dufty, Executive Manager of Policy and Research at St Vincents de Paul Society – which requested the AEMC’s rule change, says such thinking undercuts the bigger picture. “There is a structural issue here we are trying to deal with. Its not about PV alone,” Dufty told pv magazine Australia. “It’s an intergenerational wealth transfer issue.”

Echoing the AEMC’s Chief Executive Benn Barr, Dufty says two-way pricing is really about building a future framework which can integrate technologies like electric vehicles and batteries, which are not yet widely adopted. He is stedfast that community arbitrage is the best way to build a future-proof system and in turn decarbonise quickly and efficiently. “Where’s the alternative?” he questioned.

“The current framework is a tax on the young and to suggest moving forward is a tax on the sun is just plain wrong, myopic and not thinking of a distributed energy future,” Dufty said.

Why solar has been posited as a plaything of the rich

The AEMC’s two-way pricing rule change has been championed by St Vincent de Paul and the Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS), which both claim solar is disproportionately taken up by richer Australians, benefitting the upper echelons of society and driving up the electricity bills of those who cannot afford to participate.

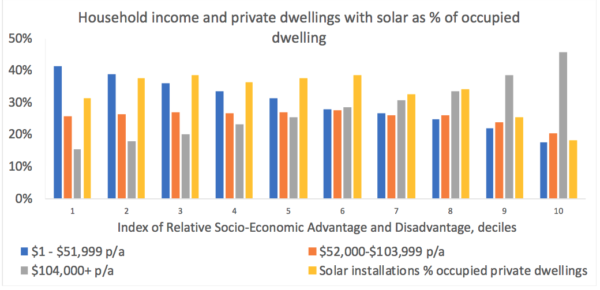

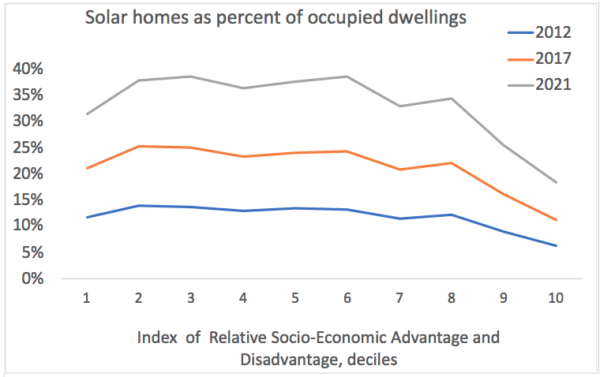

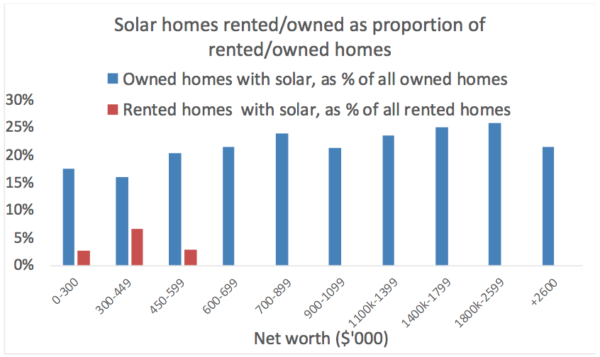

While the Victoria Energy Policy Centre’s paper acknowledges the righteous pursuit of equity within Australia’s energy markets, it claims the studies both of these groups have founded their thinking on have a glaring oversight. That is, the studies they cite do not properly segment solar installations to account for owned homes versus rented ones.

“They are aware that rentals/apartments are in a different position, but they have failed to properly understand the implications of this for the understanding of the relationship between wealth and solar uptake,” Mountain noted. Renters and people living in apartments cannot access solar, he says, primarily because of property rights, building form and transaction costs. “The barrier is not wealth.”

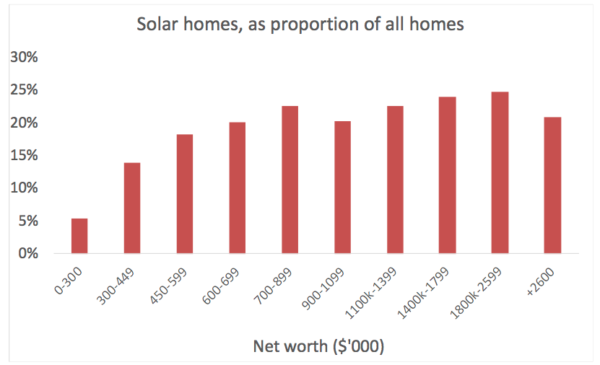

Low income owned-homes install more solar than richer households

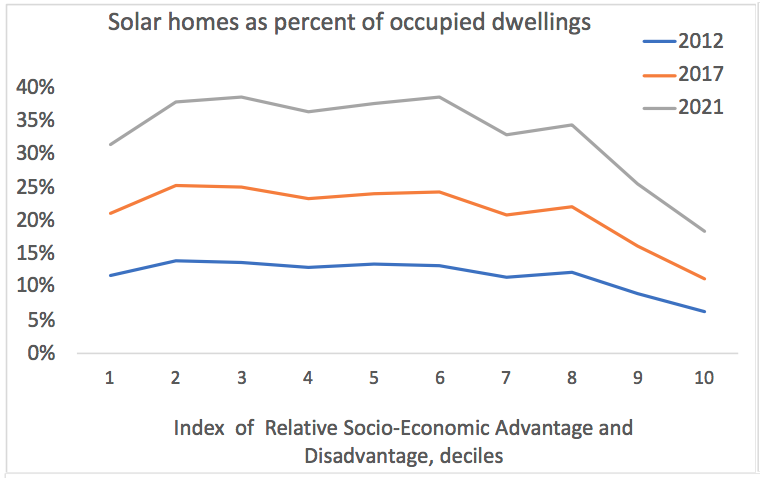

“So to understand the relationship between wealth and solar uptake it is necessary to look at the market where these barriers do not exist (i.e. owned homes, typically semi or fully detached). When we look at this, we see that wealth and solar are not positively related,” Mountain said. “The analysis of owned homes reveals that poorer households install solar at a similar or greater rate than richer households.”

Given this vastly different reading of the data, Mountain says ACOSS’ and St Vincent de Paul’s proposals are not well-founded.

What’s causing rich household’s solar cold shoulder?

While the drop off of solar installations among the very rich in Australia is hardly central to the paper, it is interesting. Why would it be that low and middle income households install more solar than the ninth and tenth deciles of socio-economic status?

Mountain believes it could come down to the household’s location. “Many of these homes are in the inner-city and the salubrious suburbs. Bill stress is much less of an issue, heritage overlays can affect solar installation and I imagine in many of the denser parts of wealthy inner city areas, shading and roof space is an issue.”

Can you call it a tax?

Mountain believes the label of ‘sun tax’ for the two-way pricing reform is as much about accuracy as it is about ease. “Since export charges lack a rationale in economics, they are best characterised as a tax,” the paper reads.

What is meant by a ‘lack of rationale in economics’ is, essentially, that it costs networks a negligible amount to integrate rooftop solar. “In our research and commentary we have pointed to the evidence that the expenditure in question is small – typically around 1-3% of distributors’ capital outlays. Ausnet Services, Victoria’s largest distributor, suggests that recovery of this expenditure will cost households 72 cents per year,” the paper says.

Proponents of the rule change also say since solar homes consume less electricity from the grid it leaves more of the distributors’ sunk costs to be recovered from other customers. Mountain disputes this also. “Our study of the situation in Victoria found that between 2010 and 2019, per capita electricity consumption in Victoria declined by 25%, of which 10 percentage points was explained by self-consumption of rooftop solar, with the remaining 15% explained by other factors. The solar-related reduction in network volumes resulted in network usage charges that are $1.3/MWh or about 0.3% (of the typical retail price of electricity) higher than they otherwise would be. This is obviously inconsequentially small,” the paper reads.

“The point here is that rooftop solar is not driving any meaningful amount of additional expenditure (for integration) and neither are the volume effects from self-consumption worth much,” Mountain told pv magazine Australia.

Bigger picture: ‘It’s not a tax on the sun, it’s a tax on your kids’

Such quibbling around solar though, Dufty says, is really neither here nor there. “It’s conflated [the issue] right down and its missing the bigger picture.” As Executive Manager of Policy and Research at St Vincents de Paul Society, he said the objective of two-way pricing is to build framework which can integrate all the future-forms of distributed energy resources.

“It’s not about just supporting solar but enabling all appliances to fit together,” he told pv magazine Australia. “I think the context is being conflated to not look to the future.”

As for the differences between owned homes versus rentals, what’s causing the barrier is hardly the most interesting issue, Dufty says. Whether or not its price, the end effect is that rental properties rarely install solar. Given that income inequality is growing and more Australians are being forced to rent, this feeds into a system which is inherently unfair. For Dufty, the fact of the matter is that those trapped in the rental market are disproportionately young people and low income Australians. They won’t get to enjoy the benefits of solar while older Australians who brought before the housing bubble can – it’s this broad societal division which concerns him.

“There’s an intergenerational equity issue here,” he said. “We are compounding that issue because of policy frameworks set in electricity system.”

He argues whatever the cause, the effect is that younger Australians have a far harder time buying a house than their predecessors, so they shouldn’t have to also foot any bills for a technology they can’t even access. For Dufty, it seems to be as much a matter of principle as actual cost of integrating rooftop solar. “Energy is a social system, we are all connected. We need frameworks which underpin that.”

Spurred by what he described as a “lack of federal government policy aspirations,” bodies like the Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS) are stepping into that space. To share rewards, you need a pricing framework which can socialise cost across everyone. Dufty holds that two-way pricing is the best and fairest way to integrate renewables and create a thriving arbitrage system. “Doing nothing is not an option.”

AEMC’s response

The AEMC provided pv magazine Australia with the following response: The AEMC hasn’t had the opportunity to consider the report but the research we have relied on to date has been published in rigorous peer reviewed journals by the leading experts in this field.

We are legally bound to make decisions that work in the long-term interests of all energy consumers. When the market works efficiently, consumers benefit. Making the market work better is central to the reforms we are looking at now and is consistent with our public comments to date about the importance of making sure that the system works for everyone whether they have solar or not.

We are currently considering all of the submissions we have received. When we make a final decision we will outline our thinking and further explain what we took into consideration.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.