After spending a year in consultations, it took just hours for the outcry to begin. In March, the Australian Energy Market Commission, Australia’s energy rule maker, released its draft rule determination – a massive reform package focussed on how to integrate new energy technologies like solar and batteries into Australia’s electricity grid.

“It’s a profound change,” the Commission’s Chief Executive, Benn Barr, told pv magazine Australia about the determination. Perhaps the most profound of the proposed changes, he says, is that for the first time distributed energy exports will become classified as a service.

“It’s kind of got lost though,” Barr says.

The reforms the Commission put forward unfold in three parts, but just one has guzzled virtually all of the attention – two-way pricing or, as it has been dubbed, the ‘solar tax.’ Basically, the Commission wants to remove the rule banning electricity networks from charging solar households for exporting.

Whether networks take up this opportunity and how they decide to structure it will be managed on a case-by-case basis. Nonetheless, the change has drawn outrage from many corners, who have lobbed the criticism that it disincentivises solar at a time when we desperately need to decarbonise our electricity grid.

The Commission is adamant this is not the case. “We want more customers to have solar but we don’t want to do it in an inefficient way,” Barr says.

We will come to two-way pricing and the Commission’s defence, but first what’s been overlooked and why it matters.

Distributed Energy Resource (DER) export as a service

Currently, networks need to comply with a number of rules as part the service target performance incentive scheme (STPIS) – but since exports are not classed as a service, there are neither rewards nor punishments for how networks manage them. And since there are neither rewards nor punishments at stake, few networks have bothered to invest serious money into making export services better.

In other words, networks don’t have a reason to make their grid work for solar customers. And often they don’t.

For example, in areas where the grid is already congested by high rooftop solar penetrations – as is the case in parts of South Australia – networks have stopped allowing new solar customers to export their surplus electricity into the grid at all. Another way some networks have dealt with congestion is by introducing blanket export limits. So even if a household has installed 10 kW of solar on its roof, it could never export more than 5 kW.

Clean Energy Regulator

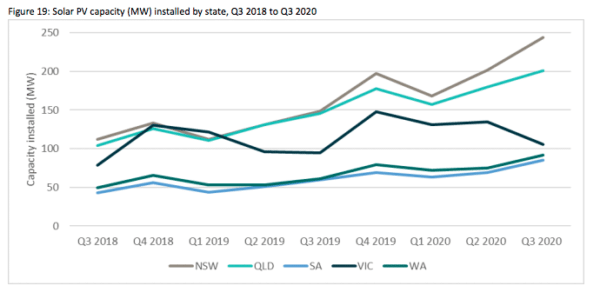

While this is only happening in particularly congested grids today, the rate at which Australians are installing rooftop solar means such measures will undoubtedly become more common.

What lays behind these blunt measures is that few networks actually have visibility over what’s actually going on in today’s increasingly complicated grid, and how customer exports are affecting it. Rather than investing the time and, more importantly, money to find out, networks naturally opt for the easiest fix, which is simply to stop exports happening.

Which is why the Commission is proposing that exports be classed as a service. Its thinking is that this shift will prompt investment by networks.

“For the first time, network businesses need to take [exports] into account,” Barr explains.

Barr is keen to ensure those investments, however, are not just in traditional poles and wires, but in new technologies which will help networks better manage the electricity systems.

The other key component of the service classification, Barr says, is that regulators will be better able to hold networks to account.

Network’s export policies now fall under Regulator

The regulator in this case is the Australia Energy Regulator (AER), which will expand its oversight under the Commission’s proposed changes. Given that energy companies regularly rank among the least trusted brands in Australia, and since networks have hardly tripped over themselves to integrate solar households, concerns about handing them more power to charge customers have unsurprisingly been churned up in recent discussions.

To his, Barr says the proposed changes to the regulatory framework will mean networks literally “have to” consult much more closely with the Regulator. “We’re giving the Regulator the final say on whatever the poles and wires businesses come up with,” he says. “There’s a lot of protections for customers in the draft.”

Endeavour Energy

Two-way pricing, also dubbed the dreaded ‘solar tax’

Which brings us to two-way pricing – giving networks the opportunity to charge solar customers for exporting when during times of surplus of supply in the middle of the day. The change has been labelled anti-solar, which the Commission insists it is not.

“We all want more distributed energy in the grid,” Barr says. But we need to integrate it in ways that are helpful and make sense.

Barr is also quick to point out the Commission’s role is to design for the future. “How the Commission makes its decision is it looks at the long term,” he says. Part of that is ensuring all consumers to benefit, not just early solar adopters who haven’t suffered from export caps or limits.

“It’s not just about solar PV either,” he adds. Batteries and electric vehicles are also front of mind. “That wave is coming,” Barr says, so it’s crucial to integrate the needs of those newer technologies into rules.

While increased rooftop solar penetrations can be seen as beneficial for the broader community by driving down wholesale electricity prices, they can also be costly for networks – especially when prices are pushed into negatives which can destabilise the grid.

Ausgrid

This is where two-way pricing comes in – the Commission says its a way of making sure the grid gets electricity when its needed, which is something we need to plan for if we want to keep our it stable.

“Two way pricing allows a signal to be sent as an incentive,” Barr says.

It’s also hoped that this change will help drive batteries and other technologies like smart home systems which can help smooth out the so-called midday duck curve. While household batteries are still too expensive to be financially viable for the majority of households, prices are falling fast, and other technosolutions like smart meters are quickly filling the gaps. The Commission’s hope is the rule change would hasten these onto the market.

Be that as it may, notable players like the Victorian government have expressed concerns about the two-way pricing proposal. “It is not clear why a charge that dissuades export of low-cost clean energy will deliver a net positive outcome for consumers,” Victorian government said in its submission to the Commission regarding the draft.

New South Wales’ Energy and Environment Minister, Matt Kean, has also voiced trepidations about the move, as has Queensland’s Mick de Brenni.

Even companies like Tesla and Enphase, which both sell storage and energy management products the new rule are designed to promote, said they not sold on two-way pricing. For instance, Tesla is concerned about the impacts the changes might have on Virtual Power Plants, suggesting community batteries could flatten the curves two-way pricing tries to resolve.

What happens now

Submissions for the draft rule determination closed on May 27, and the Commission is currently reviewing them.

In light of these responses, Barr says the Commission will decide whether it should alter its draft.

Ultimately, Australia’s electricity grid’s transition is going to cost real money. The question the Commission is grappling with is who is responsible for paying?

It’s final answer to this rather unenviable question is expected in July.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.