Wesfarmers, Mitsui and the Japanese government on Monday announced they will conduct feasibility studies into building a billion dollar “low carbon” ammonia export facility in Western Australia, another way of saying it plans to use fossil fuels and ‘capture’ the carbon. Japan’s Mitsui owns 50% of the Waitsia gas field in the state’s mid-west alongside Beach Energy, a company backed by media moguel Kerry Stokes. The Waitsia project sparked controversy in August after it was exempted from the state’s ban on onshore gas exports at premier Mark McGowan’s behest. That’s another story, but suffice to say fossil fuel industries in Australia have friends in high places.

Western Australia’s government, which is going big on hydrogen, has also given millions for hydrogen to be blended into gas networks. Atco, the gas distributor behind Western Australia’s blending program, is far from the only company-state pairing pursuing this pathway, with plans emerging across Australia, including Tasmania, South Australia, New South Wales, Queensland, Victoria.

Behind each of these plans lays the supposition that hydrogen will simply, cleanly and neatly replace our current fuels. It will one day flood our gas pipelines and launder our dirty substances so they can again be sold to hungry, presumably unquestioning, markets. Think: our world, exactly as it is, only powered by hydrogen.

Andrew Horvath, for one, isn’t convinced.

Horvath is the founder and global chairman of hydrogen technology company Star Scientific. He is also the only Australian selected to sit on the Sustainable Energy Council’s World Hydrogen Advisory Board.

He flatly calls hydrogen gas blending “stupid”. Unlike most clean energy advocates though, he does believe gas will be part of the energy transition – less because it’s a lower carbon option and more because millions of Australian households already have it hooked up.

“Where [gas companies] cross the line is saying, ‘Hey let’s run a turbine and put 20% gas in it and that shows we are decarbonising.’ Well no, it doesn’t. It just shows you don’t know physics,” he told pv magazine Australia.

“The problem with that is hydrogen doesn’t burn the way other things do.” Hydrogen has a lower energy density than natural gas, so mixing it into pipelines means spending more to produce less, he says.

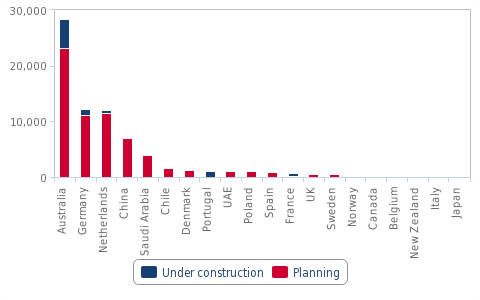

Fitch Solutions

The Energy Transition Hub’s strategic advisory panel member, Scott Hamilton, is less barbed in his take on hydrogen gas blending, though he sees its prospects as very limited. “In the short term, if we can do things to help bring the tech [green hydrogen] in, then I’m pragmatic about that,” Hamilton told pv magazine Australia.

“What it’s really gearing us up for is the large scale production of hydrogen, renewable ammonia, green steel, and green aluminium… and that’s the money.”

Blue hydrogen

Again unlike other clean energy voices, Horvath is skeptical the burgeoning hydrogen industry will be satisfied taking solar offcuts, running their electrolysers in the middle of the day when the dreaded duck rears its curvy head. Instead, he thinks it’s far more likely hydrogen producers will want to be generating round the clock – a promise clearly most deliverable by using the process of steam reforming.

But Horvath isn’t buying that either. “I equate it to making hydrogen with a ball and chain around it, using gas,” he said. It simply isn’t good practice to make a multimillion dollar investment into something known to have a problem from day one, he says.

Scott Hamilton agrees, pointing out the elephant in the blue hydrogen room: “the huge amount of vested interest in propping up fossil fuels.” These vested interests run through many levels of Australian government and of them we must be “wary and conscious”.

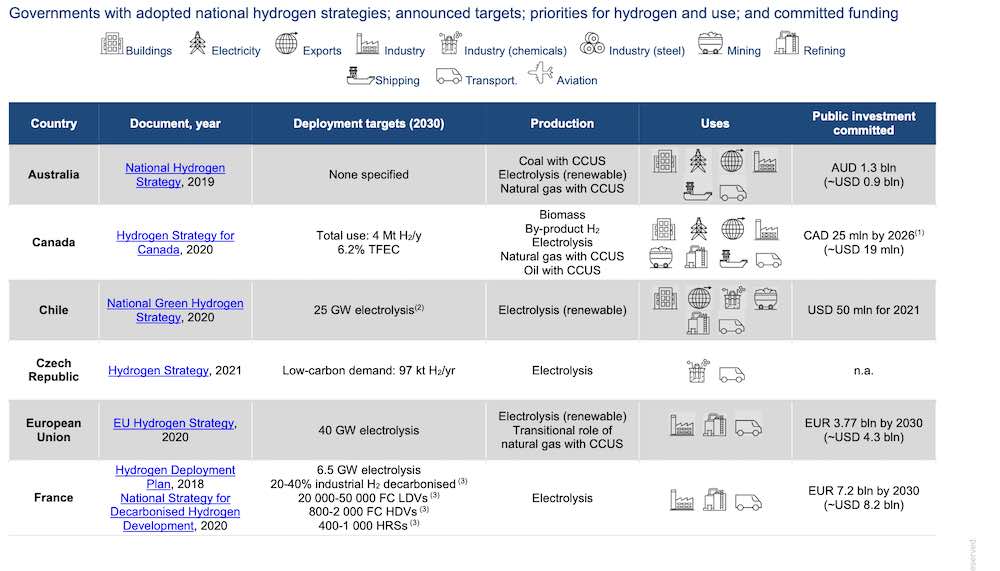

International Energy Agency (IEA)

The transition according to Horvath

So what will the future look like? Well, Horvath is an advocate for reusing existing infrastructure (which is actually one of the pillars proponents of a like-for-like transition rest their case on). His version looks a bit different though, with his company positing quite a novel way of using hydrogen.

Rather than burning it or generating electricity from it by using a fuel cell, Horvath thinks hydrogen should be used in conjunction with Star Scientific’s Hydrogen Energy Release Optimiser (HERO) technology which can be coated on any surface. When hydrogen meets the HERO technology it reacts to generate temperatures of around 700 degrees Celsius. This holds promise for infrastructure reuse because the technology, according to the company, can be easily layered on existing spinning mass turbines in traditional thermal systems.

Image: Star Scientific

Star Scientific is marketing its technology as something of a ‘demand activator’, which is to say Horvath’s longterm vision looks slightly different to the short term introduction of hydrogen into thermal systems to save stranded assets.

Looking further into the future, Horvath believes energy systems will probably look more like a series of interconnected microgrids. Instead of Australia’s expansive and rather poorly connected network, he says the country’s energy systems will likely be decluttered and made up of many smaller nodes which will incorporate distributed energy resources like solar as well as having small turbines running on (unburned, reacting) hydrogen to provide baseload power.

The future won’t look like the past

Obviously companies and the powerful lobbies they employ aren’t going down without a fight, and Horvath doesn’t begrudge them of that. But they need to invest more money in understanding new technologies like hydrogen, Horvath says. Both Horvath and Hamilton believe big companies can and should be part of the clean energy transition, but that involvement must be predicated on knowing the future won’t look like the past.

The notion that future energy systems will just be tweaked versions of their current form is, for Horvath, a sign of small thinking. The introduction of the electricity grid, the world’s largest man-made machine, seismically changed society and completely overturned old systems. The clean energy transition, he expects, will too.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

In my opinion blue hydrogen is an idea to confuse our non-technical politicians. The company might make promises about moving to green hydrogen in the future but the Government should limit the time until all the blue hydrogen is replaced by green. Of course the producers of blue hydrogen would complain that they are going to be left with huge loss of capital from their stranded assets. They might be expecting that they can complain loudly enough and take other measures to get the rules changed. From what we see with recent governments it wont be hard to change the rules. Labour should announce that as soon as they are elected they will change the rules regardless. No sovereign risk because they would be in no doubt before they make the investment.