This week’s drama around the plunging price of Australian Carbon Credit Units, or ACCUs, and the glaring question of why a government would chose to handover rights it owned is, quite honestly, mystifying. The strangeness begins with the Morrison government’s Emissions Reduction Fund itself and continues all the way until you arrive at the question of why it would want to devalue the credits when higher prices would advantage the projects it claims to champion.

Given the perplexing situation, pv magazine Australia spoke to experts about what they think is happening, and why.

The Emissions Reduction Fund

It’s difficult to grasp what’s happening here without a foundational understanding of what the Morrison government’s Emissions Reduction Fund actually is.

Core Markets

Basically the fund incentivises projects which the government says abate carbon. To give you a taste of the fund’s most popular “methods,” as they’re known, the first is called ‘human–induced regeneration’ and it involves putting a fence around a piece of land so it can’t be accessed. Another is called avoidance deforestation, which awards landholders carbon credits for not cutting down trees. All fine activities, albeit more likely impacted by rain than human intervention.

For each these activities, proponents are credited with ACCUs measured in tonnes.

How well these carbon abatement projects work has been widely questioned for a whole range of reasons, largely because people think most of the 38 methods or projects probably would have happened naturally so the government shouldn’t be wasting taxpayer dollars incentivising them.

“You can safely say, 75% of carbon credits in the Australian market are ‘hot air,’” Australian Institute’s Climate and Energy advisor Polly Hemming told pv magazine Australia.

The players in the game

Players in this scheme include the landholders, often farmers, the federal government via the Clean Energy Regulator, and carbon credit aggregators.

These guys, the aggregators, drive around to farms and properties and recruit landholders to start ‘carbon farming.’ These aggregators manage the credits, bundling them together and making handsome returns. Among the biggest carbon credit aggregators are companies GreenCollar and AgriProve.

Historically, the federal government has been the primary purchaser of these credits. It allocated a whopping $4.5 billion to pay for these projects.

What happened this weekend

On Friday evening, the Federal Minister for Industry, Energy and Emissions Reduction, Angus Taylor, announced he would give carbon credit creators the option to step away from the contracts they’d entered into with the government which would have seen them paid less than they can now get on the private market.

Image: Scott Morrison / Facebook

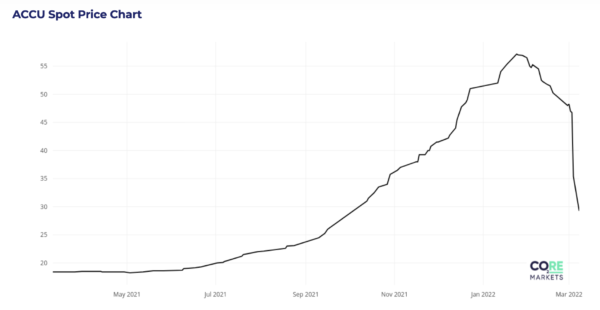

The average ‘fixed delivery price’ the government had agreed to pay for these credits was around $12 per ACCU. On the private spot market last week though an ACCU was worth around $50.

Instead of keeping the contracts, the minister allowed an out clause.

“Commercially it doesn’t make sense,” Director of the Victoria Energy Policy Centre, Bruce Mountain, told pv magazine Australia. “The government had the entitlement to all of that gain. Why has it forgone that?”

“I think it’s begging for an explanation,” Mountain said.

Taylor’s office declined to comment, simply pointing back to the minister’s previous release which categorised the decision as a win for government.

Unsurprisingly, the price of carbon credits dropped immediately following the announcement, plunging from close to $50 a tonne to today being valued at $29, losing more than 40% of their value within a few days.

Where will the money go?

Taylor has said the $1.3 billion the government wouldn’t have to pay out should the contracts be voided would be reinvested into the scheme. “That’s just a misconstruction though,” Mountain said. “It’s not a gain for the government.’*

Whether the money goes to the landholders and farmers, as Taylor has implied, Mountain believes will largely depend on the contract they had with the carbon traders.

GreenCollar chief executive James Schultz has since said the “vast majority” would go to landholders, but Mountain and Hemming are skeptical.

“The argument that these carbon credit companies are going to share the gains with the landholders and what-have-you is, I suspect, in large measure, nonsense.”

At best, Mountain says the government could have access to information it hasn’t made public as to why stepping back from lucrative contracts would be a sensible thing to do.

At worst, it may be a case of dirty dealing, someone getting an ill gotten gain.

The bigger deal

As Hemming sees it though, the bigger question is why the government is increasing the supply of carbon credits which inevitably pushes down their value.

It pointed out the federal government has been fast tracking new “methods” or project types which can access the scheme. It said the government has also been varying existing methods, allowing more carbon credits to come out of the same piece of land, as well as lowering the bar for project participation.

All of these actions would increase the supply of credits, which Hemming says does the opposite of the scheme’s stated purpose of emissions reduction.

As Hemming sees it: if you want to reduce emissions, you want carbon credits to be expensive and in demand. This would encourage farmers and other landholders to enter the scheme.

Moreover, it would mean big emitters would be forced to change their ways because they couldn’t simply buy offsets and continue with business as usual.

Cheap carbon credits benefit Australia’s biggest emitters like AGL, Origin, and EnergyAustralia, Hemming said. “As it stands [ACCUs] are so affordable… it’s just always cheaper to go for the offset.”

“No one is having to do anything, so the effect on emissions is nothing,” Hemming said.

The Emissions Reduction Fund “can’t be all things to all people,” she added. Either it reduces emissions by making that route more attractive than polluting, or it allows carbon credits to be affordable.

Long term, it isn’t clear what effect flooding the market with credits could have. “It’s hard to see what’s going to happen in terms of new projects feeling safe to come into the scheme,” Hemming said.

Carbon aggregators always win

Hemming noted that whichever route you go, the common player is the carbon aggregator. “No matter what, they are profiting.”

The role carbon aggregators and traders have played in the design of the scheme has also been questioned. Some believe they’ve been able to influence how carbon credits are developed and regulated in Australia – which is obviously cause for concern since it would benefit them.

*This article was amended on March 16 as it was learned the federal government is not able to resell ACCUs.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.