We’re increasingly hearing about the ‘circular economy’, but why are we not applying these principles to the largest transformation of our times – the energy transition?

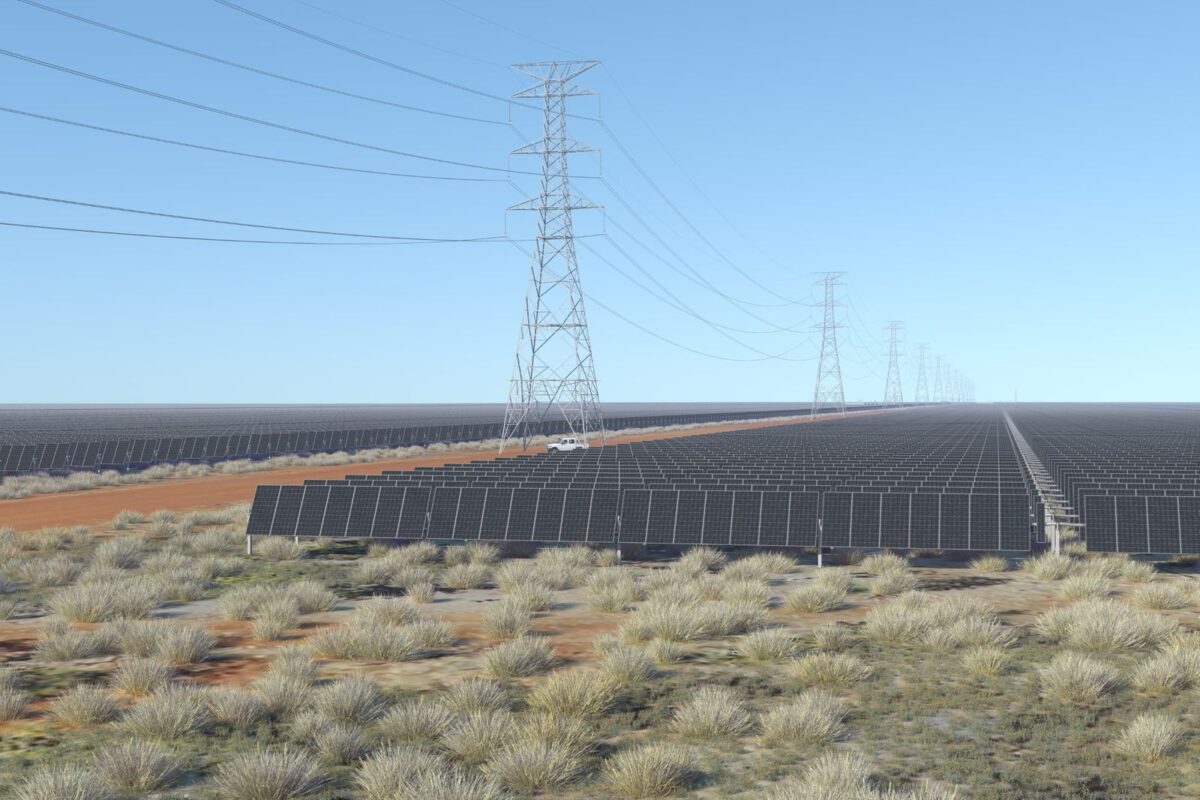

By 2050, 65% of the electricity in the National Energy Market will be from rooftop solar, producing around 70 gigawatts, according to the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO).

We are spending more than $5 billion (USD 3.14b) per year on solar installations, however less than 1.0% of Australia’s installed solar panels are made in Australia. Most panels, and their component parts, come from China.

That exposes Australia to the risk that our future energy system relies solely on favourable trade relationships with another country. Associated risks include importing low-quality panels that go to landfill long before their claimed ‘thirty-year life’, and inadvertently relying on forced labour to provide us cheap renewables hardware.

You can’t build a circular economy from a supply chain that has forced labour in its manufacture and landfill at its decommissioning.

Sheffield University’s In Broad Daylight report alleges that in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region of China, an estimated 2.6 million Uighurs and Kazakhs are imprisoned and forced to labour in the polysilicon industries that create cells for solar panels.

We also know that the thousands of solar panels that are taken off roofs every week could amount to 100,000 tonnes of modules by 2035.

If we manufacture some of our renewable energy needs in Australia, we give ourselves an opportunity to take control of these systemic sustainability issues, while also weaning ourselves off a reliance on other nations for our energy infrastructure.

Recently the International Energy Agency (IEA) released a special report on Solar PV Global Supply Chains which pointed to China’s dominance of solar PV. The IEA argued that in order to avoid the risks of industrial concentration, nations other than China must build their own capability to make all or some of the components of a solar panel.

India and the United States have embarked on policies aimed at domestic manufacturing of renewables hardware, and in Australia we – as Australia’s only manufacturer of solar panels – have been investigating how to make an Australian solar panel with as few imported components as possible. Our conclusion is that an Australian solar panel with at least 50 per cent of components by value made or derived in Australia, could kickstart a Circular Solar ecosystem. If we could produce half of the components of a solar panel in Australia, we’d not only control the quality of the panel, but we’d ensure no forced labour in the supply chains and a recycling guarantee at decommissioning. We’d be building a sustainable and ethical domestic industry.

Tindo is working with University of NSW and the Australian PV Institute (APVI) to explore detailed options for local PV Manufacturing in Australia. It’s clear from early work that in order to drive a domestic solar panel industry and supply chains, we need manufacturing scale of at least 1 GW per annum. Currently Tindo Solar, Australia’s only manufacturer, produces around 100 MW per annum.

Starting with a scenario of Australian solar panel production of 1 GW per annum, using imported components, we could drive down the cost of making a solar panel from 0.50¢ per watt to 0.33¢.

A more ambitious scenario would see most panel components made domestically from local resources. Australia would probably not build its own solar cell because that entails four vertical sub-industries, making it uneconomic for Australia.

However, Australia does have an advantage in the products already exported by our mining industry that are processed into solar panel components in China. These components – including glass, aluminium frames, junction boxes, EVA and backsheet – could be made in Australia for a domestic solar panel industry.

By making all the non-cell components in Australia we would save around $15 million per 1 GW of production, $10 million of which is saved on logistics costs from not importing PV glass.

These savings are conservative and don’t include the value-added sales Australian producers could make by refining, processing and manufacturing what otherwise is a bulk commodity export to Asia.

A domestic solar panel industry and supply chain first requires scale (at least 1 GW per annum). We also need the three layers of government to coordinate policies that give procurement weighting to Australia-made renewables products; our governments must also enforce anti-dumping and forced labour laws and consider policy settings that incentivise investment.

We see an opportunity for this country to make a sustainable investment in clean energy, by combining industrial policy with the energy transition, and building sustainability into the product.

We’re calling it ‘Circular Solar’ – the ability to ensure sustainable supply chains free of forced and child labour, a genuine 25-year performance warranty for the panel (not just a theoretical one), and a recycling guarantee for a decommissioned panel.

Circular Solar allows us to take domestic control of issues such as slavery, recycling, safety, and panel longevity, that cannot be guaranteed by relying solely in imports.

Most important, domestic manufacturing of solar panels, from Australian resources, would build sovereign capability, jobs and energy security at a time when the nation needs it most.

–

Author: Shayne Jaenisch. Shayne served as the Chief Executive Officer of Tindo Solar for more than five years, but stepped down in October.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those held by pv magazine.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

1 comment

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.