For Hamilton, Australia’s discussions on hydrogen to date have been something of a circular economy, “but in a bad way,” the BayWa r.e. Australia technology innovation and hydrogen lead tells pv magazine Australia. It goes round and round failing to recognise the closing window.

As for the theoretical vision, Hamilton thinks basing it on big ammonia exports and trying to cluster projects into hydrogen hubs amounts to barking up the wrong tree, or at least, a problematic one.

In the meantime, Australia is utterly failing to create markets for its hydrogen, he says. In his eyes, there is really nothing to “unlock” the opportunity here. “That is really worrying because I don’t see any investment activity underpinning that.”

Megaprojects trying to skip to the end of the story, to emerge at the multibillion dollar industry endpoint, is obviously a strategic play. But for it to work a lot of other growth needs to happen first.

“The sequence is all wrong,” Hamilton says. “We do something creative in shifting demand for some of the products.”

Asia “underwhelms”

Australia’s most publicised hydrogen projects to date focus on exporting ammonia to international markets, primarily countries like Japan and South Korea.

Recently, Hamilton attended what he describes as “pretty much the All Energy of Japan.” There, wind and solar buzzed but “the hydrogen stream was just void of activity.

It had poor turnout, with very little interest outside of the main oil and gas proponents, he says. Moreover it seemed to draw no major government support nor any policy movement. “It just really underwhelmed.”

Adding to Hamilton’s concern, South Australia had a delegation in Tokyo that same week working on hydrogen. “None of that was even mentioned.” Despite happening in parallel, there was no dot joining, no momentum.

“I sort of came away with a different view. Like, is this actually going to happen? What we don’t have is time to wait for those big international markets to evolve.”

Europe moves on green products, Australia stalls

Hydrogen outlooks in Europe, the core market for BayWa r.e., are very different. There, Hamilton says real investment is happening and, more importantly, there is clear visibility on subsidies, as well as demand.

That rapid development Hamilton finds worrying, largely because it is leaving Australia in its wake.

“That market is pretty quickly moving towards green commodities,” he says, meaning things like green steel, green cements and other manufactured goods.

“What we [Australia] are talking about is hydrogen as a fuel. So ammonia is largely being pushed as a fuel, and they’ll co-fire it in thermal assets. That’s a mistake because think how do we shop for fuel? Everyone’s consumer preference is the same: it’s price sensitive,” Hamilton says.

Image: HySTRA

“If you push hydrogen into that space, it’s very much viewed on a price comparison basis and it’s always going to be more expensive.

“What’s happening behind the green commodities is it’s not a fuel anymore, it’s a molecule. So it’s actually a chemical feedstock or a supply chain feedstock going into making something. As soon as you view hydrogen as a molecule, it’s a tangible product that people can market.”

Hamilton believes history has shown that people are willing to pay more for consumables if they can see a social and environmental benefit.

“That’s why I say we’ve done a really poor job in creating the market, because none of the Australian discussions are around any of those green commodities. And it’s a shame because we’re actually missing the value behind having hydrogen.”

That value is the smart applicability of the molecule itself, the applicability of hydrogen and hydrocarbons.

“Green steel is something you hear all the time, but its literally everything – plastics, cosmetics, insecticides, the list goes on and on across almost every industry. Almost everyone has some hydrocarbon exposure and hydrogen is definitely going to be the solution to unlock that.”

Stahl-Zentrum/ArcelorMittal

“The question is when it makes sense to transition different industries, when it’s going to hit a scale where it starts to be commercially viable, and who’s going to go first,” says Hamilton. The fear is that whoever goes first will pay the biggest price and so there is a hesitancy to be the first mover in Australia.

Australia’s lack of enthusiasm about developing a green consumables industry puzzles Hamilton – especially because we have such massive advantages in the race. Aside from holding all the raw materials, Australia doesn’t have a major existing steel manufacturing sector.

Far from a disadvantage, he sees this as a leg up. European governments today face a real fight trying to transition incumbent industry without destroying investments already made in equipment like blast furnaces, which tend to have around a 50-year lifespan.

In short, Australia’s green consumable industry could bloom unencumbered by the fear of stranded assets.

Green consumables also solve Australia’s geographical problem – which has hung over much of the green hydrogen and ammonia export discussion. “Instead of the freight cost being 50% plus of the delivered commodity cost, it’s maybe 5% [for green steel].”

Such a move into green products would inevitably involve a massive capital outlay, he says – something he believes would “definitely” be worth it. “Industry would match that funding,” he adds, saying there is no shortage of equity looking for green homes.

The issue is government needs to give the green light – something which can really only come from the federal level, given the “international flavour of proponents coming in to seed this.”

“If it’s not national, they don’t have any visibility.” As good as Matt Kean’s hydrogen strategy might be, it isn’t really on the radar of most international players, according to Hamilton.

Asian Renewable Energy Hub

To name one overlooked play, Hamilton points to the Asian Renewable Energy Hub, the colossal 26 GW project put forward by InerContinental Energy, CWP Global, Macquarie Capital and bp in Western Australia’s Pilbara region.

Image: AREH/Google Maps

Why would the Asian Renewable Energy Hub not move into manufacturing a Pilbara-centric bunch of green commodities, he questions. “That would be mind blowing in terms of jobs and industry establishment. I thought the government would be super excited by that, but I’m not seeing any signs of life.”

“If you can make green steel, there’s a market for it.” This, Hamilton says, is hardly true for green ammonia, at least in the near term.

“It’s not about the dollar per kilogram of hydrogen, it’s actually about the suppliers that move. I think we’re missing that window.”

Fortescue Future Industries

Hamilton points to Fortescue Future Industries (FFI), run by iron ore tycoon Andrew Forrest, as one of the few companies in the hydrogen space actually doing a good job creating its market, noting the company had more offtake arrangements than anyone else he’s aware of.

But while FFI is an Australian company, Hamilton feels like its rhetoric of late has been shifting away from the early cheerleading of Australia as the heart of its hydrogen ambitions. Rather, it is increasingly developing projects in countries like Egypt and Morocco, he says – which makes commercial sense but leaves a big question mark over what exactly Australia’s role will be.

Image: Fortescue Future Industries / Facebook

Governments missing the mark

Compounding that question is the issue of government – largely federal government – positioning, which Hamilton sees as all wrong in both its focus and subsidisation methods. “The money commitments are vastly inadequate to do anything.”

To date, there has been a massive “talking circuit” around hydrogen hubs being this obvious pathway to build scale, Hamilton says. “But I don’t actually see any of that working.”

“Governments saying: ‘Okay, we’re serious about this because XYZ hydrogen hub initiative has $200 million of government funding’ – that’s not effective. The scale at which we need to seed the foundations for hydrogen uptake is such that, I don’t see it working if it’s not a feed-in tariff.”

“We need something simple.” That is, a clear, transparent subsidy open to everyone that can be used to pay for some of the cost of production, Hamilton says.

Currently in Europe, hydrogen feed-in tariffs are being used to pay for roughly 70% to 75% of the cost of production, Hamilton says. “And guess what – it’s working.”

What doesn’t work in Hamilton’s eyes is governments trying to pick one or two projects, or one or two regions for production. “And secondly, the government is actually terrible at doing that, trying to pick winners.”

Image: Wollongong City Council

Invariably, he says, they gravitate towards big incumbents – companies which almost always have “legacy baggage.”

You then find yourself at a table filled with AGL, Origin and EnergyAustralia, he says, “and that’s a very similar landscape that we have sitting behind all these hydrogen hubs. It’s incumbent utilities that control a lot of that industrial footprint at Gladstone or Port Kembla, and I’m not sure they’re the best vehicles to move [hydrogen in Australia].”

While these giants obviously have a role to play, “participation needs to be broader than the incumbents,” Hamilton says.

“I almost think that’s how we ended up with the formula ‘Okay, export is the solution to everything’ because those companies just aren’t agile enough to think beyond to what the smaller domestic offtakes could be.”

None of this is to say that governments won’t be playing a crucial role – between developing a feed-in tariff as well as a sound administrative, regulation, and policy landscape, “there’s definitely lots for government to do.”

The other issue when it comes to government, Hamilton says, is in Australia hydrogen doesn’t have a clear voice. For him, the Australian Hydrogen Council’s efficacy was hampered from the start by mixing renewable energy and fossil fuel interests.

Image: Clayton Boyd

“Without that voice, of course government is going to be confused.”

Renewable generation

For Hamilton, the hydrogen ‘colour’ debate has had more than its fair share of airtime. “Every time this discussion comes up, I think it almost just needs to be shut down. Who cares. The market will decide the answer to that.”

The market answer, of course, will be green. So he sees no point haggling with blue or black or grey proponents – if they want stranded assets, that’s their decision.

Image: Fortescue Future Industries / Twitter

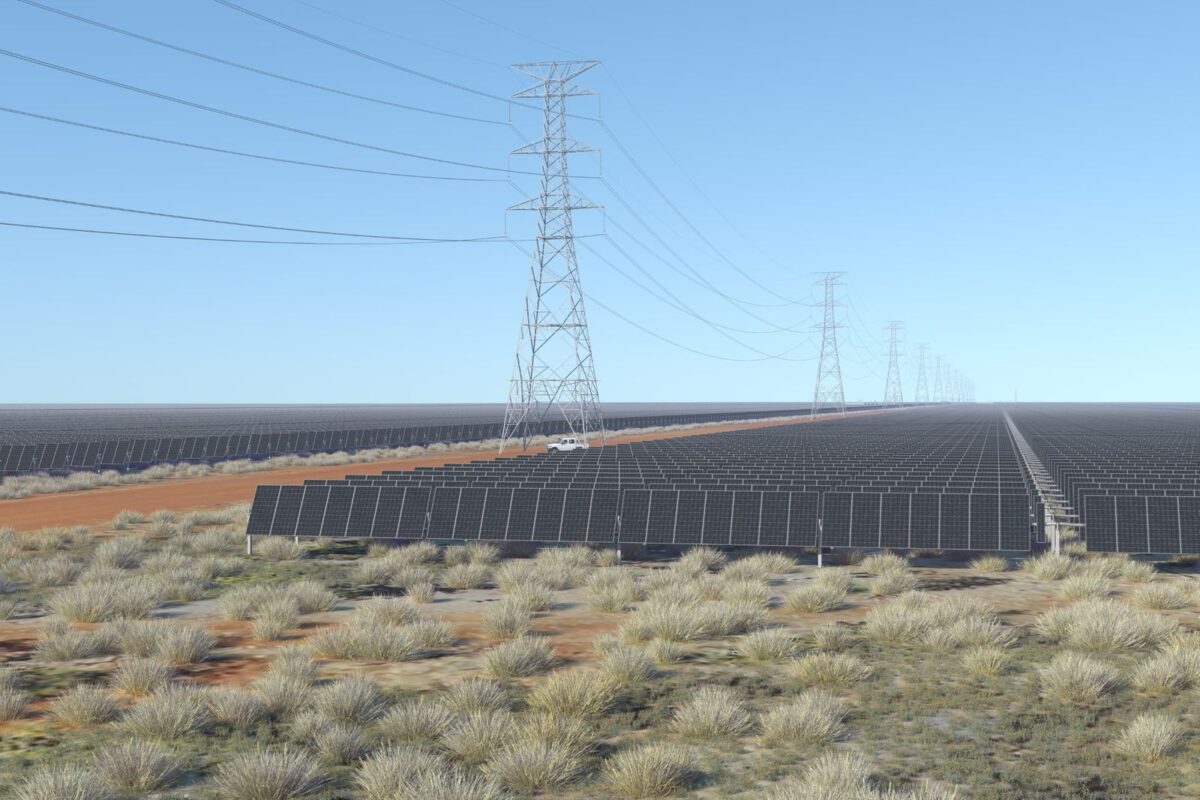

The real barrier green hydrogen is coming up against is a lack of foresight around generation. By Hamilton’s estimations, the renewable generation component of major hydrogen projects sits at around 60% to 70% of the total capital cost. On top of that, it has long lead times. So you almost need to start there in the supply chain to step into hydrogen export, he says.

While many projects consider renewable colocation, Hamilton thinks more often than not the generation capacity only accounts for a small percentage of the project’s overall needs. Which might not be such a big deal if Australia were going to have surplus capacity – but in his view, “it’s just not going to happen.”

The Australian Energy Market Operator’s (AEMO) plan for Australia’s grid transformation, known as its Integrated System Plan or ISP, is already really ambitious, Hamilton says. Australia is going to struggle to meet those targets, let alone generate significantly more renewables than needed.

A finishing analogy

Hamilton jokes that his role at BayWa r.e. is a good analogy for the overall landscape. Doing a lot of work around hydrogen in Europe, BayWa r.e. decided it would be good to instate someone in the Asia Pacific region – à la Hamilton, who had previously worked as lead researcher for the hydrogen economy at the University of Tasmania.

In his 18 months in the role, he has only ever delivered battery storage projects through the pipeline, never hydrogen.

While he’s an enthusiast, without clarity on what Australia is actually trying to do with hydrogen, and without actual projects to deliver useful products in the near term, the country’s determination to enter the global race seems somewhat misguided.

Hydrogen isn’t a primary energy source, and it won’t be a “cure all” fuel – rather its potential lies in the manufacturing of green products, and eventually filling in the gaps at the tail end of broader decarbonisation processes.

“I don’t know that I have the answers… but what I do see doesn’t fill me with confidence that anyone else has the answers either.”

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

Solar energy is the future, both rooftop (with export limiting and remote shutoff) and large scale solar instillation.

PV is proven tech and is cost effective (and becoming cheaper) Hydrogen (or green hydrogen as the fossil fuel companies call it) is an unproven tech and it will cost billions just to see if it works.

I sure dont want a potential Hindenburg located near Sydney or Brisbane