From ISSUE 12 – 2022

When Hurricane Fiona made landfall in Puerto Rico on Sept. 18, it was a Category 1 storm that lacked the brute force winds of the Category 4 Hurricane Maria, which battered the island in 2017. Maria resulted in the deaths of almost 3,000 people and plunged the island into an 11-month blackout – a US record. Unfortunately, what Fiona lacked in wind speed was made up for in flooding rains. On an island whose people and infrastructure were still recovering from the 2017 devastation, the arrival of Hurricane Fiona saw Puerto Rico’s notoriously unstable grid collapse all over again.

Surviving the storm

Between the two major hurricanes, the island was also struck by an earthquake in 2019 that knocked the grid offline for a week. The aftershocks of that quake are still being felt today, so it’s fair to say that Puerto Ricans know better than most that a natural disaster’s destruction often lives on as disruption. “This [Sept. 18] hurricane hit us very hard in all aspects,” says Gabriel Pérez Sepúlveda, a Puerto Rican solar and storage industry veteran now heading regional sales for battery storage manufacturer Blue Planet Energy. Weeks later and at least 100,000 people were still reportedly powerless. Months on and Pérez says blackouts in evening peak hours remain a daily occurrence. “We didn’t have ways to get money, we didn’t have ways to find fuel, we are an island, it’s very hard.” That confrontation with daily difficulty and an undependable grid means Puerto Ricans have been turning to solar and battery storage for resilience.

It was in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria in 2017 that Puerto Ricans realised that solar had become a means of survival. Noticing this need amidst the destruction of that historic storm, non-profit organization Solar Responders reached out to the chief of the Puerto Rico Fire Department, who confirmed that no fire station on the island had electricity and emergency services couldn’t reach many communities. Solar Responders founder Hunter Johansson tells pv magazine that the company now owns and operates 227 kW of PV and 633 kWh of battery storage across 19 fire stations in Puerto Rico.

When Hurricane Fiona subsequently knocked out the Puerto Rico Power Authority (PREPA) grid, analysis of the impact on 12 of Solar Responders’ solar-plus-storage systems found that while the grid was out for almost 2,000 hours, the systems powered each fire station for an average of 65% of that time, and some as high as 98%.

“With power, fire fighters were able to respond to emergency calls and coordinate mutual aid between stations,” says Johansson. “During this period, the fire stations themselves transformed into resiliency hubs for community residents to receive refuge, refrigerate medication, power medical equipment, collect ice, use the internet, and charge cell phones.”

Image: US Army Corps of Engineers South Atlantic Division

Image: US Army Corps of Engineers South Atlantic Division

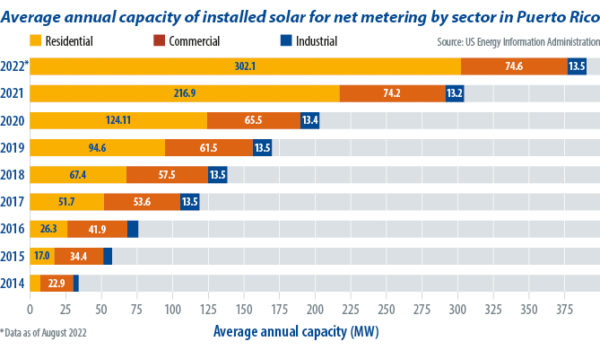

“Hurricane Maria was the trigger,” reiterates Pérez, who notes that per capita Puerto Rico is one of the most solar and battery embracing jurisdictions in the United States. “Maria is what kick-started the battery industry here on the island. We have sun, we know that works, but if we don’t have batteries and there’s no grid, we’re out of energy. So that’s how the revolution of energy storage started.”

This isn’t exactly a surprise – after all, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory found that Puerto Rico’s solar resources were capable of generating four times more power than it currently consumes. But thanks to lessons hard learned from hurricanes, solar is not enough on its own. “Now, in Puerto Rico, we see storage as a necessity, like having the internet in your home or a refrigerator,” he says. “Batteries are a no-brainer. These natural disasters are becoming bigger, and we’re seeing the importance of resiliency.”

Micro benefits macro

Citing the prevalence of tropical storms and the instability of the Puerto Rican grid with its voltage fluctuations, Pérez claims that if a battery system can work in Puerto Rico, it can work anywhere. “That’s why I say Puerto Rico is a laboratory.”

Pérez is not alone in thinking Puerto Rico a strong model for both energy resilience in the face of catastrophe and the wider transition to more efficient green energy systems. Interestingly, this is not a top-down model, but a model in which distributed energy systems and community-based microgrids not only provide energy resilience for Puerto Ricans, but also help to support the grid. “There is a long road ahead,” says Pérez. “But we can become a model for other islands and other countries to be more resilient.”

This sense of Puerto Rico as a laboratory for grid redevelopment is not just a nice idea to put some optimistic gloss on a catastrophic situation. Indeed, after the success of a microgrid in the mountain community of Castañer in the heart of Puerto Rico, the US Department of Energy decided to use the microgrid as a “dynamic laboratory” for the transmission and distribution provider LUMA to monitor how such distributed resources can help to bring back power after an outage.

The Castañer microgrid consists of 225 kW of solar, 500 kWh of battery storage, and is the product of the community’s own organisation and the New York-based Interstate Renewable Energy Council’s (IREC) Solar Business Accelerator Program, which is funded by the US Department of Commerce’s Economic Development Administration (EDA).

IREC Program Director Carlos Alberto Velázquez says the success of the microgrid system during Hurricane Fiona, not just for the five local businesses it powers but the resiliency hub it created when the grid failed, means it has “already been identified as an important component of the new grid, albeit a tiny part, but in the future there will be hundreds of these microgrids across Puerto Rico.”

Transmission intermissions

Despite 70% of the island’s population living in the north, 70% of Puerto Rico’s electricity is generated in the south and transported via highly hurricane susceptible transmission wires over the island’s remote and mountainous interior. Hence why mountain communities like Castañer are ideal locations for a resilient microgrid.

“There’s a really good opportunity here,” continues Velázquez. “Microgrids can be done on small scales. But with the possibility of virtual power plants (VPPs), all of a sudden you can take a whole bunch of microgrids and scale them up to be part of the integrated solution for the utility.” PREPA took action on this front following Fiona, selecting California-headquartered Sunrun to deploy the island’s first large-scale distributed storage program, a 17 MW VPP network of more than 7,000 residential solar-plus-storage systems.

According to Sunrun, customers can expect to benefit from on-site and back-up power cost savings, as well as compensation for feeding storage capacity back into the grid, creating resiliency for all. Sunrun CEO Mary Powell says the program looks to combat energy insecurity on the island “by switching the model so that solar energy is generated on rooftops and stored in batteries to power each home, and then shared with neighbours, creating a clean shared energy economy.”

On the back of the Castañer microgrid’s well-publicised success and large-scale announcements like the Sunrun VPP, Velázquez says “more and more communities want microgrids and understand that microgrids can be part of their solution.”

With demand not an issue, IREC program manager Loraima Jaramillo explains what’s really stopping wider adoption on the island – organisation and financing. “There are still steps we need to take in every aspect of renewable energy development in Puerto Rico,” says Jaramillo. “It’s like we’re trying to redesign the plane at the same time as we’re flying it.”

Credit where it’s due

Nevertheless, Jaramillo is optimistic that now, “finally, we have people on board from the community, from the government, from the federal government and from industry. We do, however, still need to work with the financial institutions.”

One of the main difficulties with financial institutions is the concept of “community credit.” Financial institutions are still struggling to determine how credit worthy a community offtaker is versus an individual offtaker. “It’s simple to establish an individual user,” says Velázquez. “But a community comes together with all kinds of assets and attributes to organise a community-based energy solution, how do you translate that into credit worthiness so that money can be loaned out to them? That discussion is ongoing.”

Jaramillo says “financial institutions could have a different perspective on creditworthiness if they also consider that by installing PV, you’re substituting one bill for another, not adding another bill.” This financial blind spot is limiting lower-income people from entering the market. However, there are signs of improvement among Puerto Rico’s Cooperativas, or savings and loans co-ops. Aurelio Arroyo González, executive president of Cooperativa Jesús Obrero, says there has been a “substantial increase in residential solar storage loan origination by cooperativas,” noting that between 2019 and 2021 the cooperativa renewable energy loan portfolio increased by over $27 million or 329.4%. Though González confirmed that a financing model for community microgrids has still not been created.

Knowledge is power

Hurricane Maria may have been the trigger to accelerate uptake of PV and storage in the search for resilience, but Hurricane Fiona showed that there’s also a learning curve that goes with any concerted change. Pérez, Jaramillo and Velázquez all agreed that the impact of Fiona was compounded by the fact that many Puerto Ricans were not properly educated about their battery systems. “Some drained their batteries to zero, and then, the day following the hurricane was cloudy, leaving them stranded,” says Pérez, who manages his 90-year-old mother-in-law’s solar-plus-storage system, and joked that he checks in on her when she’s off-grid to make sure she only has one refrigerator running.

Jaramillo, who herself owns a small solar-plus-storage system on the balcony of her apartment that sustained her on the cloudy days following the storm, notes that “people need to learn that the storage is all they have until the sun comes out again.” It might sound like common sense, but during the blackout following Hurricane Fiona someone went to the Castañer microgrid looking to charge their Tesla. “You wouldn’t imagine it,” she said, “but it happened.”

And yet, it’s not just the consumers that need education. One of IREC’s directives is to identify the needs and opportunities for developing the solar workforce. “We’re probably going to have to train between 12,000 and 15,000 employees over the next decade or so to meet Puerto Rico’s goals,” predicts Velázquez.

There is a long way to go, but as US Department of Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm said at the Solar and Energy Storage Association of Puerto Rico (SESA) Summit held in San Juan in November, Puerto Ricans have already borne the “unacceptable” burden of an unreliable grid for too long. “There is a future out there for Puerto Rico that is powered by a grid that has been transformed to operate on renewable resources, with innovative solutions like VPPs, and microgrids, and advanced grid controls.” After many years dogged by natural disasters and fiscal crises, solar and storage can now provide Puerto Ricans with a proven tool of resilience, a power of independence, and path ahead for their energy system. As Puerto Ricans say “Pa’lante siempre” – “We always go forward.”

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

3 comments

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.