Renewable energy market analyst SunWiz recently concluded just 14% of Australia’s home batteries are connected to Virtual Power Plant (VPP) programs. Nonetheless, major retailers like Origin and AGL have stunningly claimed to have 450 MW and 200 MW worth of power ‘under orchestration’ respectively.

In fact, Origin reported in early 2022 it had over 100,000 connected services in its ‘Loop’ VPP program. This clearly can’t be all batteries since the cumulative national tally for home batteries stood at 140,000 at that time, SunWiz managing director Warwick Johnston told pv magazine Australia.

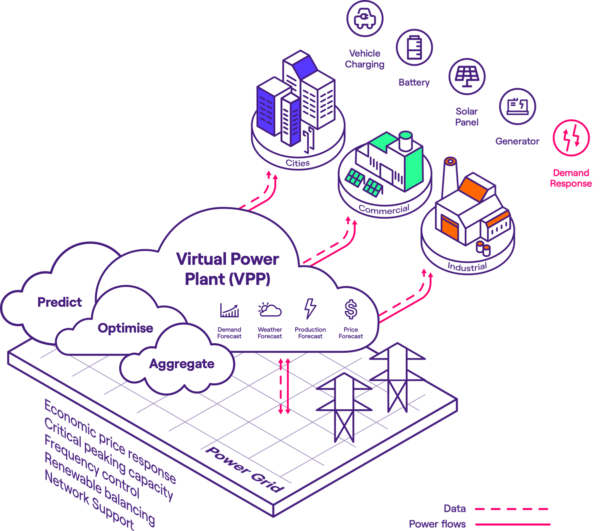

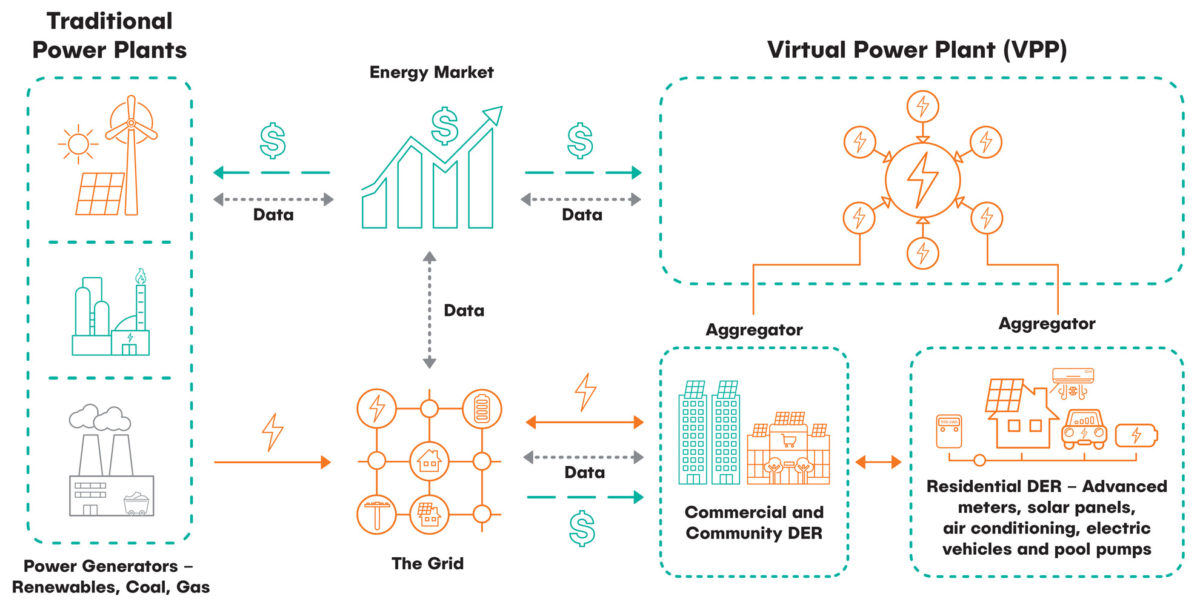

VPPs aggregate the latent potential of distributed energy resources like home batteries, combining their capacity to be able to meaningfully trade on energy spot markets, opening up new revenue streams, but also potentially providing grid support by balancing supply and demand. Given this, VPPs assets are generally taken to be flexible in their capacity to use power (for instance, a battery charging when electricity supply is high) as well as being able to flexibly supply power to the grid during shortages.

Enel X

Earlier this year, Plico, the retail arm of Perth-based renewable energy company Starling Energy Group, was notified by the Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) to provide additional capacity to Western Australia’s main grid via its VPP fleet.

Plico said more than half of its VPP’s power storage capacity was dispatched between 5pm and 7pm on January 30 to support the grid, which was threatened by soaring demand due to a local heatwave. This is an example of a VPP delivering on its promise, with WA Energy Minister Bill Johnston having described VPPs as “the future for electricity in WA.”

The disparity between retailers claimed participation and the number of batteries in Australia, however, would suggest they aren’t concerned with the actual definitions of VPPs. SunWiz’s Warwick Johnston suspects Origin and AGL are including commercial and industrial loads and residential deferrable loads as part of their VPP fleets. While, of course, flexible loads play into managing supply-and-demand, such assets offer limited support to an undersupplied, unsteady grid.*

Bella Peacock

As Johnston points out, the total size of Australia’s storage market is difficult to calculate, and the VPP market even harder still. SunWiz’s investigation into the VPP market size drew on interviews with manufacturers, VPP operators, AEMO, and combined it with other data-driven market research, Johnston said.

“The task is made more difficult by varying definitions of what a VPP is,” he said. “Some batteries are remotely controlled for an individual’s benefit, but not necessarily orchestrated with other batteries.”

As Johnston notes, electricity retailers have some ambitious targets for VPPs, “which they appear to be relying upon to replace their coal generators when they close.” If they are including mostly demand loads incapable of supplying electricity to the network under the VPP banner though, it could prove problematic.

Moreover, given the VPP adoption rate among battery owners appears to be just 14%, such hopes might be dashed. “It seems early adopters of energy storage systems aren’t willing to hand back to retailers their expensively-purchased independence,” Johnston said.

*This article was amended on April 12, altering wording from ‘no support’ to ‘limited support’ in the sentence “assets offer limited support to an undersupplied, unsteady grid.”

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

“such assets offer no support to an undersupplied, unsteady grid.”

I would strongly disagree here. There is no difference, from an energy-based view, between me removing a load or adding a generator to a stressed grid. The outcome is the same. From an asset-based view the former even is more beneficial as it reduces the load onto the infrastructure.

Hi Dirk, thanks for your comment! I see your point about it making no difference whether demand is removed or energy added. The removal of demand is, however, limited, in that only so much can be removed (or is capable of being dynamically controlled) at any time. If an undersupply remains after demand has been removed, there is no other layer of defence – thus, my comment. But I do think “no support” was probably too strong on my part, and I will amend the article to the more accurate “limited support.” Cheers!