From pv magazine ISSUE 04/23

In March, Australia’s New South Wales state government published a review of the sector’s conflicts with agriculture, a key source of community opposition, especially in slated renewable energy zones. “The friction that is emerging may be the most significant risk to policy success,” said the report.

Although conflict is pronounced in New South Wales – where a dense population, entrenched agricultural industry, and ambitious renewables program are colliding – the state is not unique.

Solar farm rejections spiked in the UK in 2021, after 23 refusals in 18 months, compared to just four between 2017 and 2020, according to local planning consultancy Turley. In the US, MIT researchers identified 53 utility scale wind, solar, and geothermal projects delayed or blocked by community opposition between 2008 and 2021. Of those, 49% were cancelled and 34% significantly delayed.

The concerns plaguing those projects resemble those in Australia. Environmental and land impact most especially – including impact on wildlife. Add in perceptions of unfair consultation, the failure to respect Indigenous land rights, and decreases in property values as key issues.

Community frustration is exacerbated by the “decide, announce, defend” approach taken by clean energy developers.

That represents a mindset pv magazine interviewees feel is at odds with the thrust of the energy transition. In Australia, stakeholders have pointed to a history of thoughtless, under-developed project proposals – feeding distrust into an already charged situation.

Opposing interests

“They just treat you like monkeys,” said Armidale Regional Council Mayor Sam Coupland, describing renewables developers in his district. His council area falls within the proposed New England Renewable Energy Zone in northeast New South Wales. “From a local government perspective, no party coming into our area has been operating in their best interests, nor our best interests,” he adds.

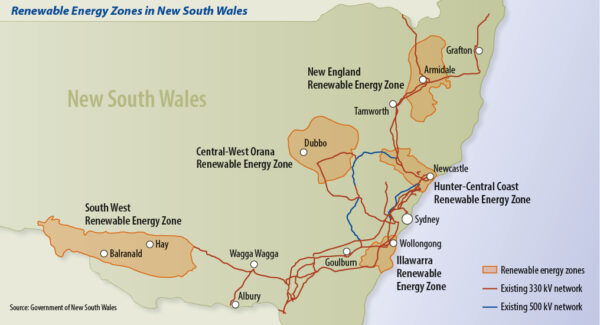

New England will be Australia’s largest renewables zone, with the state government already receiving more than 80 project submissions for 34 GW of generation capacity. The state’s renewables ambitions hinge on five such zones, in locations chosen from desktops in Sydney and announced by the state government. Since project approval rests with the state, Coupland says his council and constituents have seen “minimal engagement until the very last moment” from the four solar and seven wind developers with proposals nearby.

New England, home to some of Australia’s most productive farmers and graziers, is planned to host 8 GW of renewables capacity, so only a quarter of the interested developers should realize projects there. Nonetheless, the effects of millions of solar panels and hundreds, potentially thousands, of wind towers is causing anxiety in the community.

“This will be the biggest change in this region, on the landscape, since white men turned up with sheep in the 1840s,” Coupland says. “It fundamentally changes everything.”

Warwick Giblin, who grew up and lives in regional New South Wales, values “rural character,” even though it is difficult to qualify it. Giblin works with Coupland and other councils in the state’s renewables zones. While he is a clean energy proponent, he says he understands the upset around “sleepy, quiet, beautiful country landscapes and communities” becoming semi-industrialised at the behest of urban decision makers.

“No one ever came and sat down with the communities and said ‘let’s explain to you what a [renewable energy] zone is, we’d like to explain to you what it is and we’d like to get your ideas and input.’ They didn’t do that,” says Mark Fogerty, who consults on renewables zones.

Australia’s energy transition, Fogerty says, has been an “engineer picnic,” omitting the human element. Giblin agrees, saying “the technical and mechanistic stuff is easy compared to the humanistic and cultural.” The emotions bubbling in clean power zones resemble responses felt more broadly in Australia and beyond.

Until recently, almost no Australian energy frameworks considered project social and environmental impacts. In August 2022, state and federal energy ministers changed the National Electricity Objective to consider emissions, in a step toward decarbonisation, but other frameworks – especially those for transmission projects – do not. The process for deciding major transmission routes examines only cost, something Darren Edwards, director of community advocacy group Energy Grid Alliance, deems “laughable” given new lines are supposed to be helping protect the environment.

Without frameworks which consider the triple bottom line – “people, planet, and profit” – communities cannot trust the most credible options put forward, says Edwards, adding, “Communities know the process is flawed and the framework isn’t right, there’s no way they’re going to back down.”

Regional communities are questioning economic orthodoxy by asking how much energy the nation actually needs, as opposed to its desire to drive economic growth, and considering whether electricity is being used properly. “If we’re doing the bulk of the heavy lifting, we would like to see some evidence people are using the electricity as wisely as they can,” says Beth White, a New England farmer.

Renewables cheerleaders extrapolate the fact projects produce no direct carbon emissions to state they have no impacts. The communities hosting clean power sites know differently. Contemplating a land covered in solar panels, White thinks there is good reason to be cautious. “We don’t want to create a different problem by solving this [carbon] problem,” she tells pv magazine. “The race is being run and we don’t know the destination or the rules,” she says, hinting at an uneven playing field.

“There is a power imbalance between the developers and the locals, in that rural communities have limited ability to negotiate,” says Giblin. “Compared with the developer, they are disadvantaged because they do not have the time, technical knowledge, financial capacity, or political clout.”

For Giblin, the broader commercial context is relevant. Renewables developers in Australia are mostly private, highly profitable, and foreign-owned. “That’s a really overlooked factor,” Giblin says. “Focus for the developers is about maximising their profits, whereas from the rural community perspective, the focus is on the interplay of environmental, social, and economic costs. There needs to be real transparency around what these… costs are, and who benefits and who bears the costs. To me, that’s the nub of the issue.”

Several interviewees referred to a developer approach to environmental impact statements as “box-ticking,” and thoughtful analysis of traffic data and ecology, let alone social impacts, is a significantly harder undertaking for developers, as is validating findings at the state government approval end.

If developers and state officials have vested interests in project approvals, reviewing projects in “forensic” detail falls to the communities which, along with ecosystems, bear almost all of a project’s non-monetary costs, according to Giblin.

And developers can behave cynically, with Coupland citing “ambit claims” when companies suggest oversized, sometimes unlawful project scales before paring them back, they say, in response to community concerns. “It’s ludicrous,” Coupland says, adding that the renewables sector swans around as if doing God’s work, single-handedly saving the planet. The righteous veil is wearing thin.

In the last year, Coupland’s council has formed a coalition with New England renewable zone peers and councils from the Central-West Orana clean power zone. “As a group, we are a powerful lobbying force,” says the mayor.

With few permanent jobs at clean power plants, councils want real community benefits from projects, not just “trinkets” says White.

People want meaningful consultation. The problem is – Energy Grid Alliance’s Edwards says – “there is a significant difference between being heard and being understood.” Again, in its review, the state government urged renewables and transmission project proponents to give communities influence, rather than simply sanctioning a moment for them to yell into the void.

Better practice

Peter Leeson, director of Leeson Group, has worked as a solar developer in Australia since 2014. He has had projects enjoy broad community support and he has ideas about what developers can do to restore diminished social license. The fact that he was the only developer willing to respond to pv magazine with more than a boilerplate written response points to his community engagement chops.

For Leeson, renewables development must be principled. Consider environment and community first, he says. “Look at the site and see if it makes environmental sense to develop there. Then, and only then,” he says, should development take place. Projects should not affect native vegetation or animals. “It can be done, you just select the right site,” he says. One in five of the development proposals threatening koala habitat today are renewables projects.

Second, “you’ve got to make sure the benefits for the community outweigh the negative,” Leeson says. Every project has negatives, whether traffic-related, visual, or potential for community members to develop mental illness. Whether illnesses are physical or psychosomatic hardly matters, they require consideration, Leeson says, adding, “Make your project smaller and don’t be greedy.”

Only from this foundation should developers flesh out economic viability, Leeson adds. After that, it’s about going in, having conversations, and taking time to understand local requirements. “Nothing negates what you are going to achieve by spending a long time in the community,” Leeson says. “Understand who the leaders are.”

Image: Leesons Group

There are concerns relevant to all communities, including traffic. Narrow roads with high-speed trucks pose risks so including passing bays from the get-go makes a difference. “It’s not expensive,” says the developer, “those things work.”

Flooding due diligence is key, adds Leeson, because inadequate measures could cost neighbours dearly. While direct neighbours almost always oppose projects, Leeson says, “they are still our neighbour, we still need to do the right thing.”

And finally, donate. People want $20,000 (USD 13,300) for local clubs, Leeson says, and offering solar systems aligns with the industry’s mission.

“I think it’s actually understanding their concerns are valid… and being able to see it from the community’s perspective,” he adds.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.