From pv magazine ISSUE 10/23

From non-existent before 2017 to a gigawatt-scale fleet of operational projects at present, Australia has established itself as a global hotspot for grid scale battery energy storage system (BESS) deployment. After the first big battery was delivered following a social media wager between two billionaires, Elon Musk and Mike Cannon-Brookes, the key impetus for kickstarting the industry came from state governments and the Australian Renewable Energy Agency (ARENA). The rollout was then further propelled by a pressing need for on-demand, dispatchable electricity capacity due to a surge of intermittent renewable energy generation on the grid coupled with retiring coal plants and little appetite for private-sector gas investment.

Today there are 25 big batteries registered to participate in Australia’s National Electricity Market (NEM), and more than 200 at various stages of development. The sector is showing signs of maturity.

“We are now finding that developers and investors are getting more comfortable with understanding energy market dynamics and the strong fundamental case that exists for battery storage, particularly for shorter duration (one- to two-hour) batteries,” says Marija Petkovic, managing director at market intelligence specialist Energy Synapse.

Tackling uncertainty

By the end of last year, Australia had nearly doubled the capacity of large-scale BESS’ that were under construction, compared to the previous year. National renewables organisation the Clean Energy Council (CEC) has said that, in 2022, work began on 19 big batteries for a total of 1.38 GW/2 GWh of capacity. Looking at announced BESS capacity in all stages of the project pipeline, United States-based research firm Wood Mackenzie calculates that there are more than 40 GW worth of projects under way. Norwegian consultancy Rystad Energy counts more than 50 GW, with more than 8 GW of new utility-scale BESS projects proposed annually since 2019.

With the exception of projects built by large utilities, the key driver behind the buildout is financial support, says Rystad Energy senior analyst David Dixon. Without it, things would look much different for grid-scale BESS’ in Australia given the high capital expenditure (capex) required and the merchant nature of battery revenues.

“Banks don’t like this uncertainty and, therefore, securing finance remains extremely challenging and by far the biggest issue for this type of asset,” said Dixon. That said, although the capacity of battery projects reaching financial commitment is high, the number of projects is quite small.

The CEC has reported that in the period from April to June this year, big batteries were leading the way for financial commitments. Six projects with a total capacity of 1.5 GW/3.8 GWh broke the billion-Australian-dollar barrier during a single financial quarter for the first time.

This was largely thanks to the Waratah Super Battery in New South Wales, which alone boasts 850 MW/1.68 GWh of capacity. The project, delivered by Blackrock-owned Akaysha Energy, was able to secure finance on the back of a long-term government contract, under which at least 700 MW/1.4 GWh of the facility will operate as part of a system integrity protection scheme (SIPS) designed to monitor transmission lines and enable the battery to act as a “shock absorber” in the event of any sudden power surges, including from bush fires or lightning strikes.

In addition to SIPS, there are other support mechanisms on hand which can help get big batteries to financial close, such as ARENA grants and lower cost debt via government green bank the Clean Energy Finance Corperation. Further backing is on the horizon with the federal government’s Capacity Investment Scheme, currently in the early stages of rolling out. That program will offer long-term national underwriting agreements featuring pre-agreed revenue floors and ceilings for 6 GW/24 GWh of large-scale storage projects.

“The scheme alone is not sufficient to support the scale of investment required in storage in Australia,” said Kashish Shah, Asia-Pacific senior research analyst at Wood Mackenzie, referring to the Capacity Investment Scheme. “Nonetheless, it will attract investment in big batteries as it looks to provide revenue certainty and mitigate risks associated with declining profit margins.”

Revenue streams

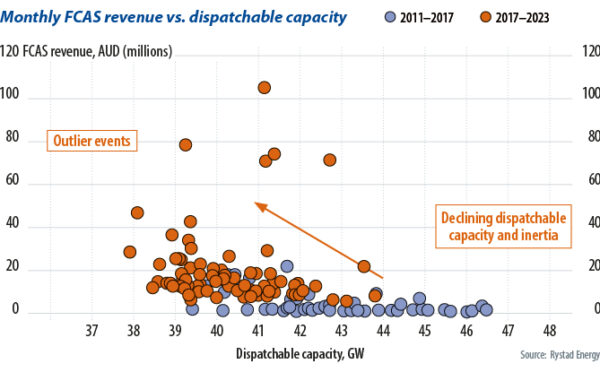

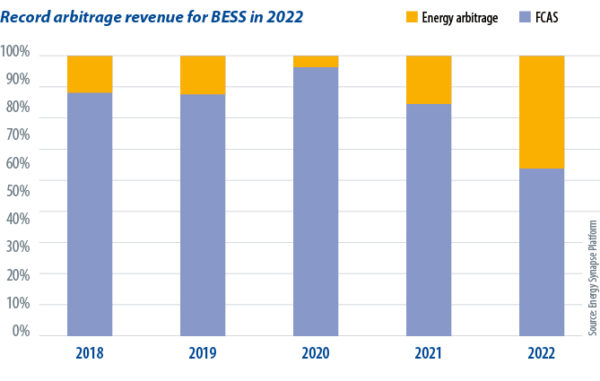

Today, big batteries in the NEM rely on two distinct revenue streams: from providing grid frequency control ancillary services (FCAS) and from energy arbitrage – charging batteries when prices are low and discharging them during higher-priced periods of the day. Historically, the former has provided the lion’s share of grid-scale BESS profit although the market has been perceived as relatively small. “The sustainability of this dependence is being questioned, given the potential for market saturation,” said Shah.

FCAS is used to maintain frequency on the electrical system, at any point in time, at close to 50 cycles per second. There are eight separate markets for the delivery of FCAS in the NEM, differing in response time – from six seconds to five minutes – and in the level of frequency deviation from 50 Hz. Wood Mackenzie has reported that, in the period from 2018 to 2021, big batteries in Australia earned 80% of their total market revenue from FCAS services alone. The proportion dropped to 49% in the first two quarters of this year. “Average FCAS prices have already started falling as battery capacity has reached 40% of FCAS volume share in 2023,” Shah said.

From 2021 onwards, big batteries in the NEM started exploring energy arbitrage opportunities as wholesale prices started to suffer big volatility. Data from Energy Synapse indicate that, in 2023 so far, market revenues of utility-scale BESS projects are tracking, on average, at 55% FCAS and 45% arbitrage. “As coal-fired power stations close and the share of variable renewable energy increases, the spread in intraday wholesale energy prices increases in a very predictable manner,” Petkovic says. “This growing spread in energy prices sends a signal to build storage to arbitrage the difference.”

Energy arbitrage proved to be particularly profitable last year when the energy market was experiencing unprecedented volatility at the peak of the global fuel crisis. Energy Synapse’s data show that in previous years, energy arbitrage contributed an average of 12% to total BESS market revenue, with the remainder coming from FCAS. In 2022, the energy arbitrage share jumped to a record-high 40%. Looking forward, it is difficult to predict how the revenue stack of big batteries in the NEM will look.

Predicting the unpredictable

The data from regulator the Australian Energy Marker Operator’s (AEMO) “Quarterly Energy Dynamics Q2 2023” report signal a shift in revenue opportunities with a 57% proportion of gross battery revenue stack coming from energy arbitrage.

Total estimated net revenue for NEM grid-scale batteries in the second quarter stood at AUD 28 million ($17.9 million), a decrease of AUD 14 million from Q2 last year. Energy arbitrage earnings decreased by AUD 8 million as a result of less volatile prices, while FCAS revenue decreased AUD 6 million, AEMO reported.

“We don’t necessarily see a permanent shift to arbitrage,” Energy Synapse’s Petkovic said. “Instead, we expect the makeup of the value stack to be quite volatile over the next 10 to 15 years. There will likely be years where arbitrage is supplying the bulk of revenue and other years where FCAS supplies the dominant share.” It is also worth noting that BESS storage duration will play a big role in shaping the revenue stack. For example, batteries with more than two hours of storage capacity will be better placed to capture arbitrage opportunities in the energy market, compared with very short duration batteries, of one hour or less. Energy Synapse observed that for batteries with less than 1.5 hours of duration, FCAS usually accounted for well over 80% of the revenue stream, compared to systems with longer storage duration, where FCAS sometimes provided less than half average revenue.

Rystad’s Dixon believes that, longer term, the greatest revenue opportunities for storage will come from shifting energy. Nonetheless, big batteries will not be economic on energy arbitrage alone.

“If capex remains in the range between AUD 700 and AUD 1,100/kWh, the levelized cost of storage is estimated to be between AUD 300 and AUD 500/MWh, well above the long term, two-hour, intra-day spreads, which are expected to remain between AUD 150 and AUD 200/MWh by 2050,” said Dixon. “This highlights the need for alternative revenue streams, such as FCAS, to underpin the battery’s revenue in order to repay the debt.”

Some believe, however, that the rapid buildout of big batteries is likely to collapse the FCAS market. “We anticipate that total battery capacity will surpass the size of the FCAS market by 2025, further hampering revenues,” Wood Mackenzie’s Shah said. As the electricity market continues to evolve, big batteries are likely to explore new revenue opportunities, such as voltage stabilization, transmission and distribution deferral, and congestion management. “Nevertheless, it is anticipated that the profit margins from these opportunities will remain relatively

modest in the short to medium term,” Shah added.

Other analysts are more optimistic, both with regard to the future of the FCAS market and future earning potential in the NEM.

“As we move to a highly renewable, low-inertia grid, the need for ancillary services to balance the grid will also grow,” said Energy Synapse’s Petkovic, adding that new markets for fast frequency response are already scheduled to start in the NEM this month.

“There are also emerging opportunities for BESS’ to be used to remediate system strength charges that transmission networks are starting to implement,” said Petkovic. “Further revenue streams will be created as the market evolves, particularly for those battery storage projects that are equipped with grid forming inverters.”

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

2 comments

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.