From pv magazine ISSUE 12/23

In October, China restricted the export of graphite products – a key ingredient in lithium batteries. The move built on an embargo of critical materials gallium and germanium that was introduced in August. China’s domination of critical minerals supply is well known and the country’s “willingness to employ export restrictions on critical minerals as a retaliatory measure,” as US Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo labeled the embargoes, has exacerbated Western fears.

Australia is at the centre of a global critical minerals frenzy. Home to one of the world’s most advanced mining industries, Australia has abundant critical mineral deposits, access to affordable renewable energy, and is a politically stable ally to the United States and European Union. The multibillion-dollar economic opportunity is clear, with governments and industry scrambling to position battery minerals at the centre of their focus. Mining magnate Gina Rinehart, for example, is pouring billions of dollars into lithium projects as fossil-fuel exports wane.

The nation’s battery minerals industry has multiple new mines – including for vanadium – beginning construction or hitting advanced stages in 2023. Refining, which is a comparatively new industry for Australia, is opening up. The nation’s first commercial lithium hydroxide was produced in 2022 thanks to a joint venture between Tianqi and Australia’s IGO – and a separate project by US giant Albermarle.

These projects are not easy to bring online, though – Australian miner TNG was renamed Tivan after its leadership was removed by shareholders. The time and finance needed to realise mining projects is immense, especially with companies wanting full-value-chain, “pit-to-product” output from mines, processing, and materials production. In October, Australia’s government doubled low-interest loan funding for miners and critical mineral processors, taking the pot to $4 billion – an “entirely insufficient” figure, said Tim Buckley, a financial analyst and director at thinktank Climate Energy Finance (CEF). What the government fails to appreciate, Buckley said, is the race for green industry and supply chains is not a free market because “America has thrown a trillion bucks at the problem.” With China now a command economy, said Buckley, “our number one customer doesn’t actually believe in free markets.”

Delicate politics

China is easily Australia’s biggest trade partner, including for critical minerals. In June 2022, 97% of Australia’s lithium exports went to China. China’s GDP that year was around USD 17.9 trillion, while Australia’s was USD 1.7 trillion.

China’s dominance means it controls many critical mineral prices. “They’re the buyer, they want the price down,” Buckley told pv magazine. Price movement was so stark in 2023, Australian business Lynas Rare Earths – the biggest non-Chinese separated rare earth producer – chose to stop selling. “It’s a real pushback,” said Buckley.

He said federal policymakers should support companies like Lynas. That could be diplomatically awkward so Buckley suggests the government use a separate entity, such as its green bank the Clean Energy Finance Corp. (CEFC). “We need the CEFC to be given a commodity book and a mandate to act strategically,” he said, suggesting the remit include rare earths, lithium, vanadium, copper, and cobalt. During price collapses, like those seen in 2023, the CEFC could buy and hold. “You just call it a strategic reserve,” Buckley said. That would have a double benefit as projects could have government-backed underwriting, a buyer of last resort. A strategy like that, Buckley said, would help Australia to wrangle price control from its trade partner.

Australia’s aim is to move beyond digging and shipping raw materials and get to the real money of refining and processing. That would make the nation a direct rival to China and other key partners such as South Korea. Ben Kim, managing director of the Australian business of Korean steelmaker Posco Group, this year warned Australia against trying to establish a battery ecosystem. It should focus on its strength in the mining sector, he said.

Australia’s aim is to move beyond digging and shipping raw materials and get to the real money of refining and processing. That would make the nation a direct rival to China and other key partners such as South Korea. Ben Kim, managing director of the Australian business of Korean steelmaker Posco Group, this year warned Australia against trying to establish a battery ecosystem. It should focus on its strength in the mining sector, he said.

There are multiple battery material markets but how can the current geopolitical situation be priced? “Previously, we had to value the green premium, now it’s the geopolitical premium,” Buckley said.

The European Union and Australia have been trying to negotiate a free trade agreement since 2018. Europe wants Australia’s critical minerals. In a shock move for Europe, negotiations were terminated in October by Australia, because the European Union refused to meet its potential partner’s agricultural demands.

Australia was also expecting an announcement clarifying its potential status as a “domestic supplier” under the US Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), during October. Despite Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade working on this from within the United States for the last six months, no announcements have been made.

While Australia’s politically aligned allies are waiting to wolf down its mineral supply, the true price of adjacent deals may prove less palatable.

Fragile ecosystems

The environmental cost of Australia’s battery mineral vision has, to date, received almost no airtime. Community opposition and the rapid erosion of the renewable energy industry’s social license is already a big issue for solar and wind projects and battery materials have likely only been spared because of the industry’s infancy.

Battery minerals sit on an extremely uncomfortable paradox: The extractive industry is necessary to store the renewable energy which will help save our climate but to get the minerals, we need to destroy natural environments. That is because, as Australian Electric Vehicle Association (AEVA) President Chris Jones explained, rare plants and ecosystems tend to occur near rare minerals.

“Basically, you get lots of diversity where some key resource is limiting,” he said. “If you have rock formations that are very close to the surface, that’s where those deficiencies are going to be really obvious. All of that speciation, that incredible plant and animal diversity that forms in the millions of years post that rock formation, that diversity is basically as a result of the rock formation being there.”

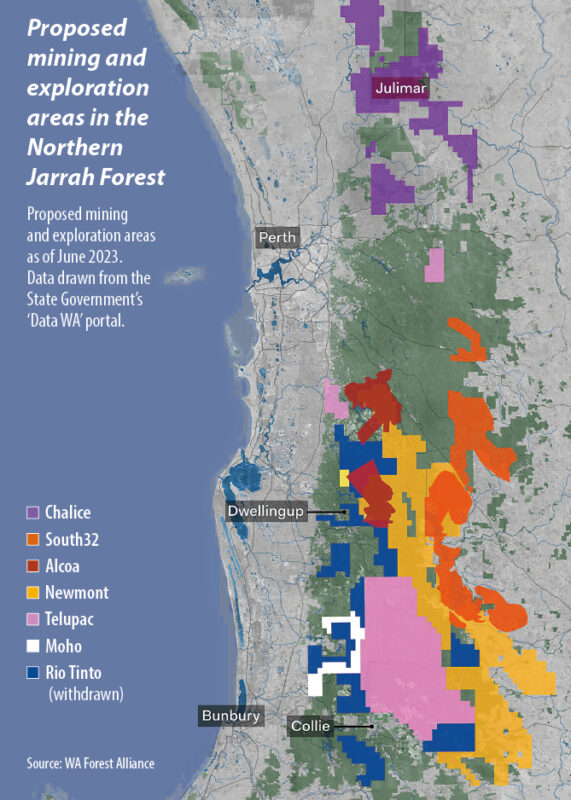

That is not to say there are no rare minerals outside delicate ecosystems – the deposits just tend to be deeper, making them harder to mine. The demand for the minerals and the technologies they are used in are comparatively new, so mapping and exploration in Australia is only just heating up. This year, federal agency Geoscience Australia launched its new nationwide Mineral Potential Mapper. Meanwhile, the state of Western Australia (WA) has seen a land grab for critical battery minerals with the number of exploration claims jumping 8% in the past 12 months. The majority of Australia’s known critical mineral deposits are in WA and, to a lesser extent, Queensland.

As Australia begins assessing its mineral deposits in earnest, both AEVA’s Jones and Jess Beckerling, the WA Forest Alliance campaign director, say it must simultaneously assess where it would be appropriate to mine.

“We are in the twin crises of climate and biodiversity. Separating them out and only looking at climate while continuing to exacerbate the biodiversity and water crises is not a solution,” Beckerling said. “We need a very mature discussion about this and we need to start from the point of: What are we trying to achieve?”

The climate is at the sharp end of the need to tackle emissions and ecological crises so it is vital to protect forests, one of our only proven carbon sinks, while accelerating decarbonisation, argue Jones and Beckerling. “Triage is, probably, exactly the right way to explain it,” said Jones. “So should we really be building luxury Mercedes Benz’ with 112 kWh batteries when electric buses are a good idea instead?”

Environmental impacts only become more pronounced when mineral mining eventually turns to onshore refining and processing. As CEF’s Buckley noted, “refining makes mining look good.” Those sensitivities continue as batteries reach their end of life, with spent devices classed as dangerous goods unsuitable for shipping, making onshore recycling necessary. This is not yet a problem in Australia, where the uptake of electric vehicles – the main demand source for batteries – has been slow.

Time to act

Nonetheless, it is a sector that Mark Urbani, founder of battery recycling company Renewable Metals, is adamant needs to be addressed today. “We know permitting is going to be a big issue and we basically need a two-year permitting period before we can even build the plant, and then there’s probably an 18-month build time. So if you wait five years to start your work, then you’re really eight, nine, 10 years away and that’s too late,” he said. “We should be taking care of our backyard.”

Renewable Metals has just completed piloting a recycling process at its plant near Perth. The main issue the company is encountering is not technical but investor hesitancy, due to limited volume of used batteries. Without any serious government support, nor any tangible recycling policy, Urbani said, “there’s no real benefit in the short term, aside from doing the right thing.”

Both he and Buckley believe Australia’s heavy haulage mining trucks could offer a clever way to kick start recycling and Australia’s overall battery ecosystem. Mining trucks work around the clock, meaning that if they were electrified, the batteries would likely only last 12 months, due to constant cycling. “So you have a perpetual recycling rate,” Buckley said, as well as local materials and manufacturing. Given the balance books of Australian miners, it is entirely feasible for those companies to transition their haulage fleets quickly if the government incentivised it.

Underlying basically all of this is perhaps Australia’s most insidious hurdle – decades of slimmed down government. “‘Small government’ means we’ve de-funded and de-skilled the government bureaucracy so now they don’t have the capacity to move fast,” Buckley said.

There is a near unanimous consensus that Australia needs a comprehensive critical minerals and battery strategy, and policy reform to enable it. These need to be clever, strategic, and bold because, unlike China, the United States, and the European Union, Australia can’t rely on scale. Yet, the frameworks delivered to date – maybe with the exception of the one in Queensland – have included very little in the way of tangible, actionable policies. “We need a strategic plan,” Buckley said.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

G’day Bella,

I enjoyed the read. Funny you mention TVN (former TNG) I have been following them a while. I actually own a solar power business in Newcastle NSW as well.

I do agree with you that Australia is beholden to other parts of the world when it comes to critical minerals and most importantly manufacturing.

There was a 6 month lead time on Tesla batteries at one stage and we are so influenced by global price fluctuations that it’s hard to provide consistent and accurate pricing models to our customers.

Such is the nature of minerals and mining, and simple supply and demand.

I’ve always believed that Australia needs to shift its focus to in-house R&D of battery technology so we can start producing our own. There is no point in mining the material if we have to ship it off to China to get manufactured for them to ship it back to us. You will find the majority of Australian battery power companies although they are owned in Australia they still have their products manufactured overseas.

In order for Australia to really progress, we need to start focusing on Australian made products.

TINDO are a good example of this. They are one of the only Australian made solar panel manufacturers competing against the behemoths of the industry. They are much more expensive than a Chinese panel, but they are totally manufactured here in Australia. The bigger they get, the better they are posied to produce panels at a more effective $p/w scenario.

The same would be true for batteries, but last i checked there are no battery cells being made here in Australia.

For the battery industry to really take off, that’s what we need. Otherwise, from the environmental front, we have no idea about if what we are doing with the batteries is actually environmentally a net positive if you consider the whole of life process. With the batteries we get from China or even America, we just don’t have that data, so no one can say that they are good for the environment because no one has done a study on the required resources to mine, transport and dispose of the battery product and it’s benefits against that of coal fired electricity.

Until we get that done in Australia, we probably won’t get the data. That’s why im hesitant to push batteries on that side of things.

https://www.newysolarco.com.au/