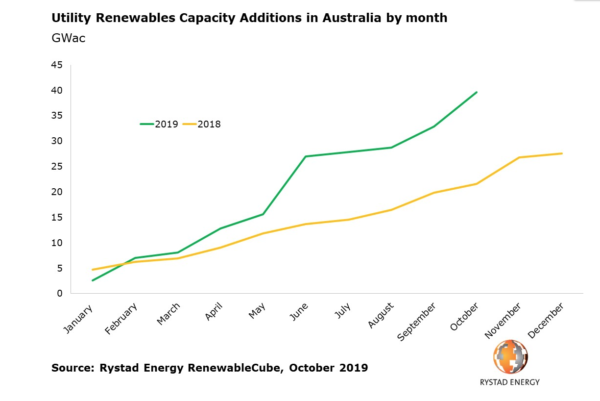

Australia’s pipeline of grid-scale solar, wind and battery projects is growing at an unprecedented pace in 2019. According to Norway-based consultants Rystad Energy, it now stands at 133 GW, up from 94 GW at the start of the year.

“New projects proposed in 2019 represent almost A$60 billion in potential investment, with large-scale solar farms leading the charge,” says David Dixon, a senior analyst on Rystad Energy’s renewables team. To date, proposals have been made for 39.4 GW of capacity, with utility-scale solar accounting for 54%. Grid-scale storage and wind account for 25% and 21% of the capacity, respectively.

The consultancy splits the projects proposed in 2019 into three broad segments. The first are renewable projects proposing to connect to the National Electricity Market (NEM). The second are projects proposed for the off-grid mining/resources industry, which consumes 10% of Australia’s total energy use and are competing with expensive gas and diesel for power generation. The third segment is the emerging export market, with several projects proposing to export solar and wind energy via hydrogen and/or High Voltage Direct Current (HVDC) transmission. “These three opportunities, combined with Australia’s global leading residential and commercial PV sector, will likely drive growth for solar PV in Australia to 35 GW in 2025,” Rystad states.

Australia currently sources around 22% of its electricity from renewables and Rystad expects this to grow significantly in the years to come as the country seeks to establish itself as a major exporter of hydrogen produced from wind and solar.“Actually, exports will drive Australia’s renewables’ share of the energy mix closer to 500% than 50% thanks to the rising number of large-scale projects fueling hydrogen generation,” Dixon said. “This year has seen an increased number of mega renewable projects in Australia, and we expect this trend to continue as state and national hydrogen strategies are forming.”

Indeed, in one of the most recent announcements, a mega clean energy project that aims to produce green hydrogen for local industry and export to Asia from up to 5,000 MW of combined wind and solar capacity was unveiled for Western Australia, with Siemens on board as technology partner. The Murchison project is the second massive green hydrogen production facility proposed for WA, following the 15 GW Asian Renewable Energy Hub (AREH) plan, which is also intended to export power to Southeast Asia via subsea cables and supply big miners and green hydrogen projects in the Pilbara region.

Another factor driving the growth in grid-scale project proposals are the planned retirements of ageing coal plants. According to Rystad, some 23 GW of coal-fired capacity is due to retire from the system, creating an opportunity for 60-70 GW of solar and wind. However, the consultancy believes the coal exit is possible even much earlier.

“Despite these projects retiring over the next 30 years, we believe coal-fired generation could be extinct by 2040 – as we expect a flood of storage projects entering the system by 2025,” Dixon said. “Coal will struggle to compete economically in this market and will also be driven out by growing consumer sentiment for cleaner fuel.”

Further growth in renewables is expected from the electrification of LNG facilities, which would address the dysfunction in Australia’s gas market. “We expect this trend to continue with energy-intensive users of power and gas – with the electrification of LNG projects presenting a silver bullet for Australia’s East Coast gas crisis,” Dixon remarked.

Emissions to drop?

The recent renewable energy boom, according to the Australian National University (ANU), will see Australia’s carbon emissions decline by as much as 4% over the next few years. Noting that Australia’s solar and wind deployment is 10 times faster per capita than the world average, Professor Andrew Blakers says: “This is a message of hope for reducing our emissions at low cost. Solar and wind energy offers the cheapest way to make deep cuts in emissions because of their low and continually falling cost.”

However, ANU researchers underline the emissions cuts will depend on the support of the federal government and, to a lesser extent, state governments to further expansion of solar and wind by ensuring adequate new electricity transmission and storage. “If the renewable energy pipeline is stopped or slowed down because of insufficient transmission and storage, then emissions may rise again from 2022,” Blakers adds.

The current renewable energy boom came on the back of the Large-scale Renewable Energy Target (LRET). While the target has been efficiently met, the Morrison government did nothing to replace it beyond 2020 and evidence has emerged that investment has slowed down. According to a briefing paper released by the Clean Energy Council (CEC) last month, financial commitments in new renewable energy projects reached a high of over 4500 MW in late 2018, but have now dropped to less than 800 MW in each of the first two quarters of 2019.

In reaction to the ANU policy briefing paper, CEC CEO Kane Thornton tweeted: “This analysis is ignorant and misleading – investment in renewable energy has already slowed.” Other analysts also expect a slowdown in new projects with investors reluctant to make financial commitments without more policy certainty.

But the ANU researchers claim the establishment of renewable energy zones to overcome outdated transmission rules and expanding interconnection between states, via an additional undersea cable between Tasmania and Victoria, would do the trick. “There are straightforward solutions to the teething problems of technical change in the energy industry – though not without some political headaches,” Blakes said.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

“Australia’s pipeline of grid-scale solar, wind and battery projects is growing at an unprecedented pace in 2019. According to Norway-based consultants Rystad Energy, it now stands at 133 GW, up from 94 GW at the start of the year.”

Interesting, just a few years ago, Australia was said to have used about 250GWh of electricity in a year. Now there is pipeline of 133 GW of projects. Over 50% of the required power generated and stored for use.