From hands-on development of the first Australian assets for global renewable energy company innogy, to the leadership of a new analytical player in Australia’s energy market — Alba Ruiz Leon is leveraging more than 15 years of experience in the energy industry in her latest role as Managing Director of global market-intelligence firm Cornwall Insight Australia.

Cornwall Insight began its Australian operations in August 2019, but it took until January 2020 to find and appoint the right person to head its team in one of the most volatile and complex electricity markets in the world.

In renewable-energy forums over the past few years, Ruiz Leon could be counted on to tell it like it is from her position as Managing Director of innogy Renewables Australia, which has been working to develop one of the biggest solar farms Australia has ever seen.

Near Balranald in renewables-thirsty New South Wales, the 349 MW, 900-hectare Limondale Solar Farm delivered its first power to the grid in August last year from the project’s 49 DC MWp Stage 2. The remaining multi megawatts are under construction and scheduled for completion in mid 2020.

Learnings from such major projects are among those that Ruiz Leon, an engineer, who also has several years of experience in energy-asset management, brings to analysis and consulting with Cornwall Insight Australia.

In this exclusive interview with pv magazine, she says she’s of a mind with her new colleagues, who are dedicated to providing unbiased data, clarity of analysis and practical advice, adding that the company’s global perspective on successful transition strategies, and its training courses in NEM dynamics, can help all invested or interested parties grasp the transition nettle.

pv magazine: What attracted you to the role at Cornwall Insight Australia?

Alba Ruiz Leon: It was the individuals and their vision that truly attracted me, and the professional but personal and caring culture of the team and executives, particularly the global CEO, Gareth Miller. We have a good mix of Australian energy market experts; among them some of the professionals who built AEMO’s ISP model for instance — the conversations over coffee in the morning can get very deep (laughs).

2020 is set to be another strong year for growth in renewable capacity in Australia; but is also tipped as the year of drastically declining investor confidence. What should investors be paying attention to?

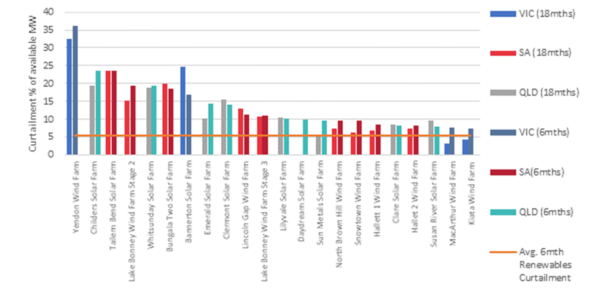

Clean energy investment has slowed over the past two quarters, falling back to 2016 levels. It’s not easy for external investors to understand how volatile the Australian market became in these last few months, with marginal loss factors (MLFs) over the cliff, projects not being able to connect when a site is fully constructed, or being curtailed by 30%, when even a curtailment of 15% can jeopardise the future viability of a project. We’ve also found that some of the panels that are coming into Australia can be of very poor quality, which also affects the returns on solar assets.

Graph: Cornwall Insight

I can understand how, in the short term, all of this negatively affects investors, and why they might stand back and say, “I’m going to wait until the Federal Government puts something in place that brings certainty to investment,” or maybe “I’ll wait until MLFs stop going down,” or “I’ll wait until AEMO can connect sites as soon as they are ready.”

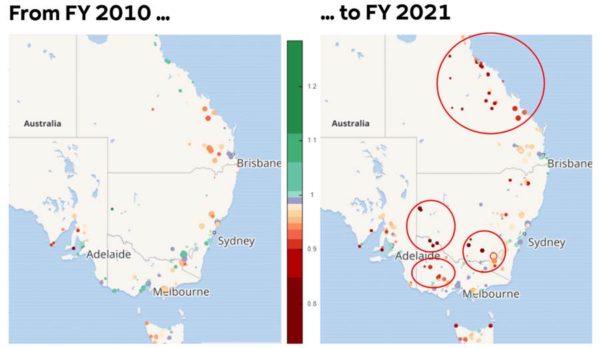

Mapping: Cornwall Insight

In the long term, with the Federal Government on board or not, we have another reality, which is that we must reach carbon neutral fairly soon. And the cheapest way to produce electricity, whether you are a green advocate or not, is solar PV.

Investors should also consider the broader Australian context: Australia is a solid, stable economic environment. More than 14 GW of coal generation is due to retire in coming years. Electricity demand is expected to increase dramatically as the country changes its transport fleet to electric vehicles. Australia has a high index of population growth — 1.4% compared to the US at 0.7%. The country has outstanding renewable resources in solar, wind and hydro. And most states and territories are rolling out or planning for battery storage to provide greater grid security.

Where do you see the opportunities for Australia’s solar industry?

I think the future is in hybrid projects, incorporating solar, wind, and storage — whether that’s batteries or pumped hydro. And the renewables industry should focus its efforts on working with communities to create jobs in areas heavily reliant on carbon-intensive mining, coal and gas extraction.

There are also opportunities in working out how renewables can best support commercial and industrial energy loads — the power purchase agreement is still an under-used instrument for bringing big energy users and renewable supply together.

Given Prime Minister’s recent arrangement with New South Wales to increase gas supply, do you include gas generation in the future hybrid mix?

I think that in the short term we’ll need some gas. In the long term, an excess of renewable generation, battery storage scattered across the geography and pumped hydro could pick up that difference. Gas is going to be very expensive, it’s high maintenance, and in terms of health and safety it’s fairly complex. So I would say that for all those reasons we would be much better off focusing on how we can really achieve 100% renewables, like Tasmania is about to do.

We expect future demand to be met by about 28 GW of solar, 10.5 GW wind, 17 GW storage and maybe 500 MW of flexible gas.

From where you now sit, what do you see as the greatest threat to Australia’s orderly transition to renewable energy?

I believe the transition to renewables is no longer in question. We are in the midst of it, but we need to work collaboratively to deliver on a couple of significant challenges.

No 1 is well recognised — we need more transmission to enable renewable energy zones where the renewable resources and land are available.

And we need to improve our system-strength issues to allow more renewable generators to connect. That is, inertia must be strategically added to the system.

How we do this needs to be talked through and put in place so that when a renewable project comes on, it does not get put on hold due to system strength issues.

What kind of options would be most practical?

There are a few conversations underway about which options and also about who pays for those options. The one that has been enforced lately is the synchronous condenser, but I don’t think it’s been handled in the best way.

If we decide synchronous condensers are the answer, we need to understand where the inertia pockets are, and put a synchronous condenser of appropriate capacity into those areas. This will allow three to five solar farms around one area to connect without destabilising the system and participants in that area might pay a fee towards the synchronous condenser. And in a perfect world it would have been ordered in advance of those renewables projects needing to connect, so there are no delays and generators are able to meet demand.

But synchronous condensers are not the only solution. We should talk openly about how batteries behind the meter can be part of the solution, or about accelerating proposed changes to inverters that would allow them to support inertia.

This bushfire season has added an extra layer of complexity to delivering consistent energy supply Australia wide. What can we do to alleviate this?

We need a well distributed and balanced generation mix across the country; for rural areas we should consider an interconnected grid of independent hybrid systems.

But natural disasters will only happen more frequently and with higher intensity until we resolve the root cause of the problem: we need to drastically reduce our carbon footprint. Some ways of achieving this are: planting trees, stopping deforestation, and of course focusing on how to build and enable a reliable system centred on renewable generation.

Where are you focusing your own industry learning at the moment?

I want to better understand how the solutions to energy transition have been arrived at in other countries, so we can apply learnings from those countries in Australia. I don’t want us to reinvent the wheel and for Australia to take 20 years to transition. I’d much rather ask where are we at? Where are the complexities that we need to address? What are our unique factors and technical conditions? And how have other countries solved for similar conditions? Perhaps we can save a good ten, maybe 15 years of due diligence and mistakes by leveraging different scenarios and solutions that have worked elsewhere.

Cornwall Insight has been in Ireland and the UK for 15 years and has analysts all over Europe. I’m going to tap into their knowledge and analytical resources for the benefit of our Australian clients and investors.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.