These were the questions at the heart of pv magazine’s Insight on Quality, hosted last week as part of the All Energy 2020 digital conference.

The event featured an unparalleled team of technologists and market participants including Nigel Morris of Solar Analytics; George Touloupas from Clean Energy Associates; PV Lab Australia’s Michelle McCann; UNSW’s Alison Ciesla; Richard Qian from Longi Solar of Eric Ast, Stäubli Electrical Connectors; Ben Macias from Shoals Technologies Group; Durmus Yildiz, from Baywa r.e. Solar Systems; Ariel Re’s Jan Napiorkowski; and finally Geoff Bragg from Sunman Solar Pty Ltd. What resulted was an in-depth look at PV module degradation, how different stakeholders are tackling it and it can be mitigated.

Degradation: what we know

Looking at data from Solar Analytics’ solar fleets, Business Development Director Nigel Morris, found that at any one time about 70% of the systems the company monitors worked fine, 22% had undetermined faults, about 7% seemed to have communications faults and only 1% had a determinable fault.

“We think this is probably indicative of what’s going on out there in the market,” Morris said, noting that the statistics remained fairly stable when looking at an individual systems or an entire set of fleets.

Morris also noted that due to extreme weather events and other unusual circumstances, faults “come and go.” There are, he said, 20 variables that can make a normal system behave abnormally, leaving us with the key question “what is normal?” in terms of PV module performance.

Both Morris and George Touloupas, Director of Technology and Quality at Clean Energy Associates, noted time inevitably increases the likelihood of issues with modules.

“Nothing lasts forever,” Touloupas said. While partly a “natural” process, Touloupas says module degradation is far from linear or even predictable.

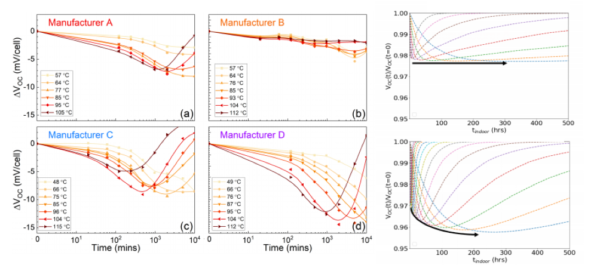

Taking light- and elevated temperature-induced (LeTID) degradation as an example, Touloupas pointed out this form of degradation is far slower than traditional Light Induced Degradation (LID). It may take years to be detected but can cause more than 10% power loss. However, after a cell reaches maximum degradation, regeneration sets in.

Building on this, Alison Ciesla, the Project Leader of Industry Collaborations at UNSW, said LeTID degradation – which is somewhat ironically believed to be caused by the hydrogen that can be used to fix other light-induced forms of degradation, can actually degrade more severely under lower light and temperature conditions. For example, the leading research institute found that in subtropical Queensland, maximum LeTID degradation was reached in about five to six years, after which the module would begin to regenerate. In temperate Tasmania, however, the cell degraded more slowly but may never recover, causing the most severe impacts.

While there are currently treatments available which can be applied to cells before they are assembled into a module, it is evident there is still a lot to be learned about this form of degradation. Luckily, Ciesla is confident that a new tool in the form of a climate chamber will improve how UNSW is able to test degradation, with hopes they can then pass this knowledge onto industry.

“This is a huge issue we still plan to study a lot in the future,” Ciesla said.

Detecting degradation

Issues with modules are brought to companies’ attention one of two ways, beginning either with angry customers or with monitoring alerts. However it begins, any potential warranty claim inevitably requires a “whole lot of data,” Morris said.

PV Lab Australia tests modules, with partner Michelle McCann pointed out that while optimisers and microinverters can indicate issues, field testing offers little more than an idea of what’s wrong. “This equipment is not made to produce accurate measurements,” Touloupas agreed.

If you’re going to convince a manufacturer to uphold a warranty – you’re going to need to go back to the lab, McCann said.

Using thermography and EL imaging, degradation can be more thoroughly inspected. Of the two tools, Touloupas said, “you can find the low hanging fruit more efficiently and cheaply with thermography.”

Looking at a case study presented by Touloupas, in which a buyer had uninstalled replacement modules which they were able to test for defects in order to make a warranty claim, McCann was doubtful such a method could be widely used. While keeping spares is a good backup and certainly proved helpful in this example, she said it’s hardly a good line of defence for smaller installers, retailers or customers.

For them, lab testing is probably most useful before modules are installed as a way of checking what has been bought. “The value that a test lab can bring is really avoiding that kind of confrontation … [because] once you get to that point it’s costly in terms of time and money,” McCann said.

Hearing from the manufacturers

Front of mind for manufacturers too, product engineer from Longi Solar, Richard Qian, said much the research and development done by his company has been devoted to minimising degradation. According to him, sourcing and using the right materials in production is “extremely important.”

He said Longi frequently test final products coming off the production lines and closely monitor their products across the world.

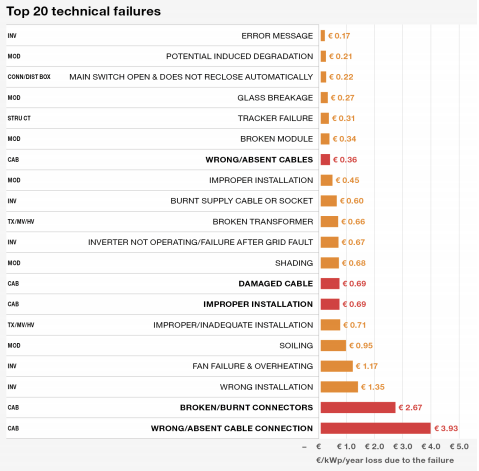

Beyond the module, a number of the participants pointed out the paramount importance of connectors and other eBOS components in ensuring the functioning of a PV system.

Ben Macias, Vice President Sales at Shoals Technologies Group described connectors as the “veins” – without them the PV system simply cannot pump electricity. Yet despite their integral role, Macias said connectors are painfully misunderstood, with many installers continuing to “cross mate” connections labelled as MC-5 compatible or comparable.

Importance of connectors and eBOS components under-appreciated

This was the core grievance of Stäubli Electrical Connectors Head of Business Development Alternative Energies, Eric Ast. He said his company has been asked to come and look at set up systems only to continue to find cross connections using components from different brands.

“We see a lot of complaints coming in about connectors even when it isn’t related to our products,” Ast said.

He believes too heavy of a focus on inverters, with not enough attention paid to eBOS components – leading to a lack of knowledge about their important. “It’s having a high impact on the profitability … as well as having risks,” Ast said.

Incorrect cable connections is one of the most costly mistakes that can be made in PV systems, and special attention should be given to components in the planning stage, the Stäubli Head of Business Development said.

Aside from increased education about cables and connections, Macias from Shoals Technologies Group said updating data sheets would be a quick and easy way to solve the common problem of system faults. “These are a big, big deal,” he said.

Shoals is also “just about ready” to release its Big Lead Monitor which will allow a far more granular and preventative type of maintenance for systems.

In terms of insurance, Ariel Re’s Global Head of Clean Energy, Jan Napiorkowski, illustrated the increasing sophistication of bespoke professional indemnity insurance underwriting solar systems.

Australia haunted by installation bad practices

According to Durmus Yildiz, Manager Director of wholesaler Baywa r.e. Solar Systems, Australia’s core issue is poor installation.

“There are still very bad practices here,” he said. Below are examples of what he called the “wrong use of a well manufactured product.”

Yildiz believes one way for Australia to move past its sometimes patchy history when it comes to installation quality is to have more compliance with STC schemes – a point Geoff Bragg, Managing Director of Sunman Solar Pty Ltd echoed. This could extend to a revamping of the STC, with the subsidy being paid on generation rather than system capacity.

“There has been some really bad stuff done in the Australian market,” Bragg agreed, pointing out that customers need both quality products and quality installation.

Given how difficult warranties are to uphold from manufacturer, Bragg said the long promised periods on PV modules are a seriously “onerous commitment” for small solar retailers and installers.

“Long warranties make excellent marketing … but that’s actually carrying a long burden for small retailers, for example, that are tied to that product.”

At the end of the day, the retailer that sold system to customer is expected to make good if there’s a problem, he said. If product manufacturer isn’t helpful, the retailers are the ones who ultimately carry burden.

You can watch the full recording of the Insight into Quality here. You can find copies of each of the participant’s presentations here on pv magazine.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.