Just as the UK announces it will bring forward its ban on sales of diesel- and petrol-driven vehicles from 2035 to 2030, a curious phenomenon — some have called it “shameful” — has gripped Australian state governments, driving them to impose an annual road tax on owners of electric vehicles (EVs); thus making up for revenue expected to be lost in fuel excise as EVs become more popular.

Just short of two weeks ago, South Australia became the first jurisdiction in the world to make moves to levy a tax on owners of electric vehicles. A few days later New South Wales Treasurer, Dominic Perottet was reported to be considering a similar scheme for his state, although that suggestion seems to have since been muffled; and on Saturday, Victoria’s Treasurer, Tim Pallas, announced the imposition of a per-kilometre tax on EV owners, in advance of announcing the state’s 2020/21 budget on Tuesday.

The moves are not entirely unexpected: arguments and analysis became particularly heated late last year when an Infrastructure Partnerships Australia report — Road User Charging for Electric Vehicles — advocated the reform of road taxes to maintain a constant source of revenue for the upkeep of Australia’s road infrastructure, and to ensure that all road users are fairly levied. Its argument being that EV drivers are currently getting off scot free.

Pallas used the kind of divisive rhetoric made popular in this lingering Trumpian era, telling reporters on Saturday that it was unfair that “a tradie driving a Hilux ute” paid fuel excise, while those driving a Tesla avoid it because they do not use petrol.”

The point is surely to enable as many people as possible to have the opportunity to consider buying an electric vehicle, by setting policies that make it attractive for manufacturers to bring a wide range of EVs to the Australian market at accessible prices.

What’s the biggest-ticket item for society today?

Reform of roads and transport funding may indeed be warranted in future, when the majority of cars on Australian roads are electric, but in the meantime it’s important to properly consider the context and reasons for accelerating, not hampering the transition to EVs.

Among the main considerations must be the need to accelerate global efforts to achieve net-zero carbon emissions and reduce the many catastrophic dangers associated with global warming.

A recent study by the University of Melbourne forecast that under current policies and the current trajectory of emissions increase, global warming will impact Australia’s economy to the tune of $1.89 trillion by 2050, with the annual damage reaching $100 billion by 2038.

In fact Professor Tom Kompas, of the university’s School of Biosciences, said the computationally comprehensive modelling had shown that Australia would sustain economic impacts equivalent to a COVID-19 pandemic every year by 2038 if a business-as-usual attitude to emissions prevails.

It’s infuriating that governments are taxing EVs – get behind this petition! https://t.co/FvJxjnOFC8

— Kane Thornton (@kanethornton) November 21, 2020

Transport must be next on the transition agenda

After electricity, transport is Australia’s largest source of emissions, and it has become like traffic noise to say that the Federal Government has no credible policy stance on reducing Australia’s overall emissions, while state governments have delivered far more prescient responses — at least in terms of their goals to transition the electricity sector towards clean energy.

Victoria, like the Federal Government, has promised an electric vehicle policy/roadmap for some time, and the industry has expressed incredulity that it would, at this very nascent stage of EV uptake in Australia, introduce a disincentive that will weigh heavily on buyers’ pockets.

Victoria’s decision to impose a tax of 2.5 cents a kilometre for fully electric vehicles and 2 cents a kilometre for plug-in hybrids, will add $500 a year to costs incurred by EV owners who drive 20,000 kilometres per annum.

This tax burden contributes to other disincentives that would-be EV owners must contend with when deciding whether or not to go zero emissions, such as the fact that most EVs currently on the market are more expensive than their petrol-driven counterparts and as a result are more often than not subject to the luxury vehicle tax.

Victoria’s expectation of raising some $30 million a year will make little contribution to the economic carnage caused by climate change.

Incentives before taxes

Even the IPA report suggested that in introducing fuel/road tax reform, “a government may also choose to provide a discount on a road user charge or registration fees [for electric-vehicle drivers] for a number of years, ensuring electric vehicles will pay less than their petrol or diesel equivalents, in recognition of the wider environmental and economic benefits electric vehicles can bring.”

It also posited that governments “can provide guarantees to electric vehicle motorists that revenue raised through a road user charge will not exceed what they would have otherwise paid in fuel excise, and that revenue will go directly to transport investment”. Less than half of today’s fuel excise of 41.8 cents per litre of petrol or diesel flows back into the transport system — the rest is guzzled by general revenue.

In South Australia, the structure of the state’s EV tax has not yet been defined, but it is expected to include a fixed annual levy plus a charge based on kilometres travelled, and will not apply to hybrid vehicles.

The Electric Vehicle Council (EVC) calculates that EVs represent only 0.6% of new vehicles sold in Australia; and that South Australia has around 2,000 electric vehicles in its overall fleet.

Expected revenue in the first year of the South Australian tax, which will come into effect in July 2021, is $1 million.

The pure economic benefits of displacing ICEVs with EVs

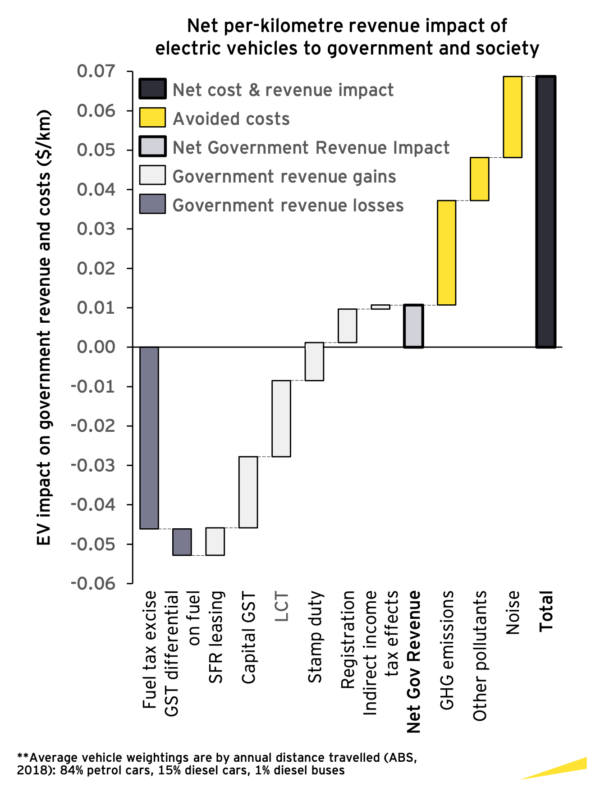

In September 2020, EY published a report, Uncovering the hidden costs and benefits of electric vehicles, commissioned by the EVC, which found that the average net benefit provided to government and society by an EV replacing an internal combustion engine vehicle (ICEV) is $8,763.

The revenue benefits to government flowed from sources including: capital expenditure taxation and registration; increased discretionary spending capacity of households due to lower running costs of EVs compared to ICEVs; diversion of spending from fuel retailing to the broader economy; and reduced demand for fuel which the cost of maintaining a strategic fuel reserve.

Cost benefits to society of displacement of ICEVs included: reductions in greenhouse gases, reductions in local air pollutants, and reductions in noise pollutants.

Image: EY/ Electric Vehicle Council

In response to state governments jumping on the EV road-tax-revenue wagon, EVC Chief Executive Behyad Jafari said: “Yes, in the long run governments won’t be receiving as much in fuel excise as people drive more efficient vehicles. But that’s a good thing. Burning less foreign oil in our cars is good for our city air, it’s good for our health, it’s good for our climate, and it’s good for our economic sovereignty.”

He makes the point that when tax is dwindling from one area, governments don’t necessarily have to recover it from that same area.

Jafari added that when EVs become commonplace, governments might need to consider new taxes to maintain transport infrastructure, “But at this point in our history, when we should be doing everything possible to encourage people to switch to electric vehicles,” he said, such taxes will be “pure poison” to encouraging positive change.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

3 comments

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.