“As a science-led organisation, we haven’t ever had a fart joke in the title of one of our reports,” says Tim Baxter, Senior Climate Council Researcher and co-author of Passing gas: Why renewables are the future, launched by the Climate Council last week. But the title is both engaging and apt for the report’s main argument, that gas must become a declining source of energy in the global system, it is not central to economic recovery from the pandemic or the means to revive Australian manufacturing.

Incorporating the latest science that is expected to inform next year’s climate change assessments by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and leveraging world-leading modelling by the Australian Energy Market Operator of pathways to transition, it clearly explains why Australia can and must devote its planning and research to accelerating development of renewables as the country’s primary source of energy.

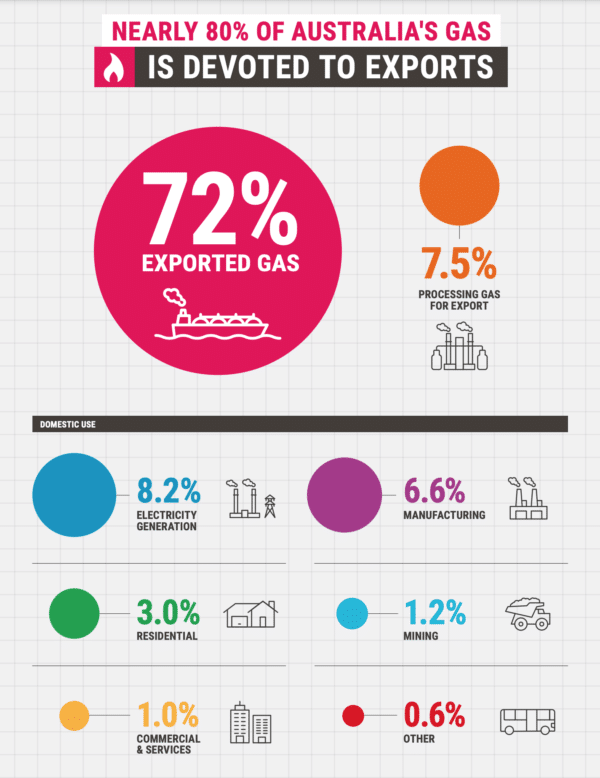

Among the key new findings of the report are: the extent to which Australia and other countries under reporting their harmful emissions from gas; that the second largest user of gas in Australia is the gas industry itself; and that, with the international gas market in crisis, Australia’s increased reliance on gas as proposed by the Federal Government exposes it to price volatility and job losses.

Image: The Climate Council

pv magazine spoke with Baxter about the report’s negative findings and its positive conclusions.

pv magazine: There have been several reports explaining why gas should be a shrinking rather than a growing component of Australia’s energy mix. What is the particular intention of this work by the Climate Council?

Tim Baxter: We were definitely joining in a chorus, but offering a different perspective. The main premise of the report is that gas as a fossil fuel is driving climate change, and that we need to move away from using it as fast as possible. That was clear before we started work on the report earlier this year. I think, more than any of the other reports we really put it in the context of climate change, both in linking to the impacts that have already been seen, but also talking about the different global warming potentials of methane [as released during gas and oil extraction]. Our sources are at the forefront of scientific research that will inform the IPCC assessment reports coming out next year. Explaining the atmospheric chemistry of things in a way that the lay person can understand is something that I think the climate Council is uniquely recognised for.

The science is evolving, and you make the point in the report that Australia’s current emissions calculations are built on old intelligence.

There’s a lot of outdated knowledge out there. Things that might once have been true are now nonsense because we’ve moved so far.

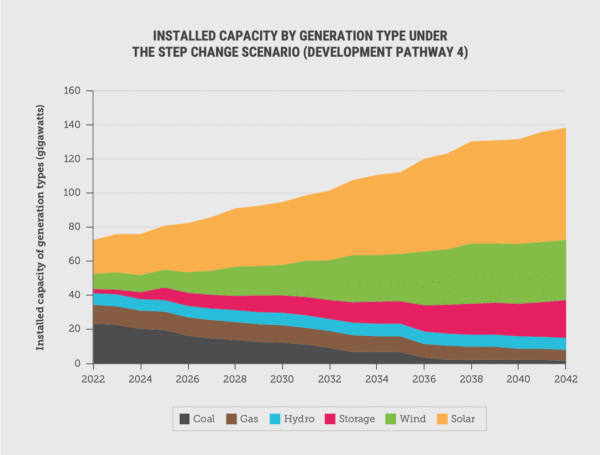

For example, the Australian Energy Market Operator’s (AEMO) 2018 Integrated System Plan (ISP) had a scenario called Increased Role for Gas. There was no such scenario in the 2020 ISP, which is evidence of the shift that’s occurred even within two years — an increased role for gas was believable within the 2018 ISP in a way that it certainly isn’t in 2020.

We’ve been stuck in this narrative that gas is an enabler of decarbonisation, and that’s a really old way of thinking about gas and its role. Ten years ago you had reports like the Garnaut Climate Change Review, which talked about transitioning from coal to gas for a short while and then moving away. One of the world’s most sophisticated energy models, the ISP, says we now don’t need more gas fossil fuelled energy production.

The draft ISP findings from AEMO came out in February with multiple pathways for decarbonisation for Australia that don’t involve new gas.

What’s changed?

We don’t need any new gas because the economics of renewables and storage have fundamentally shifted. If you’re talking just about battery storage, it’s come crashing down the cost curve; over the past 10 years the cost of batteries has fallen 90%. And of course, solar and wind have fallen down an equivalent curve, which means that even those supportive storage solutions that are relatively more expensive, like pumped hydro, have a whole different economics to play with.

Image: AEMO / The Climate Council

Future energy supply has become a matter of combining renewable technologies and leveraging their different strengths. How do you see the role of solar PV evolving as part of the mix?

I think it’s crucial. I mean, we’re the sunniest continent on the planet and the really interesting thing for me is what we’re going to do with that peak solar supply during the day. We tend to run to hydrogen and putting electrolysers around to soak up that surplus that hits at around noon. I’m not saying hydrogen’s not exciting, but when you look at feeding that essentially free midday electricity into manufacturing and heavy industry — that’s when you see how decarbonising will generate jobs. And that’s where you start ticking the win-win-win-win-win box!

It’s an exciting proposition, and it adds to the argument that a gas transition is unnecessary. Our report details why gas is a dangerous substance to be burning in the 21st century; how it has a greater than previously calculated role in driving climate change, and the latest understanding of how gas extraction is harming the health of local communities.

The report also details how investing in new gas supply and gas-fuelled power stations will slow investment in renewables and effective planning for a clean-energy-based economy.

This is one of our concerns with the CEFC Bill at the moment: not only will the Clean Energy Finance Corporation potentially be required to invest in gas, but that investment in gas will then be competing with investment in zero-emission solutions. Plus there’s the fact that it’s going into the market and muddying the waters on the signals that we need to decarbonise as soon as possible.

Investing in new gas infrastructure is going to slow down decarbonisation, not only by increasing emissions in the short term; but that new infrastructure will be operating for decades if the people who own it have any say over the matter, because it has to make a return on investment.

For the time-poor reader, what’s the most important section of the report?

Read the section that debunks the notion of gas as a transition fuel — it’s important, and it’s on a single page, like a one-pager. Then there’s the systematic under reporting of upstream emissions from gas — accounting for the impact of those emissions is extremely important. Another important piece is debunking that often repeated idea that gas produces half the emissions of coal, which is simply untrue in all but a tiny number of circumstances. Basically, the bit that’s really important is what’s between the front cover and the back cover of the report. Being literate in this stuff is an inoculation against nonsense.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

1 comment

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.