To eclipse lithium batteries in the race to become the dominant green transport fuel, hydrogen would need nothing short of a groundbreaking invention and a giant windfall of cash.

“Right now, hydrogen is not even close,” Professor Wills, Managing Director and owner of Future Smart Strategies, told pv magazine Australia.

Essentially, this is because markets tend to prefer single market solutions, Professor Wills says. In other words, monopolies. Think, for example, of Google. Despite all the hype around the potential for democratisation on the internet, just a handful of companies today own and operate the lion’s share. Once a company or technology claws the upper hand, its difficult to stop its ascent. Market advantage tends to stick.

Professor Ray Wills

Which is precisely what Professor Wills believes will happen with lithium batteries, leaving hydrogen in its wake. “Hydrogen as transport fuel is still a long way behind lithium batteries.”

This, he says, is also telling, since hydrogen has been pursued industrially for about 100 years, where lithium batteries have only been a serious staple for around 15 years. In terms of learning curves and the improved economics that goes with them, hydrogen has had a lot longer but continues to have far less impressive returns.

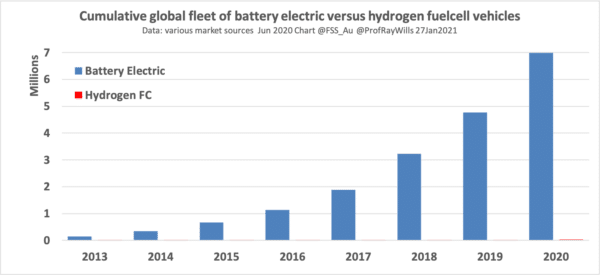

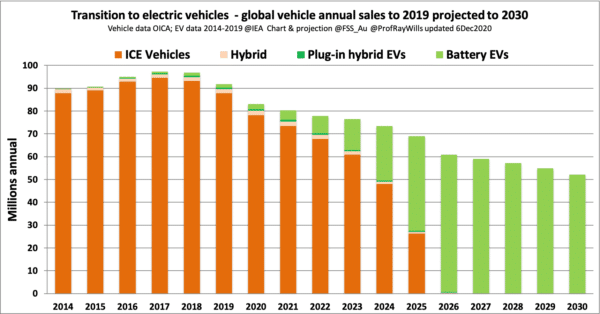

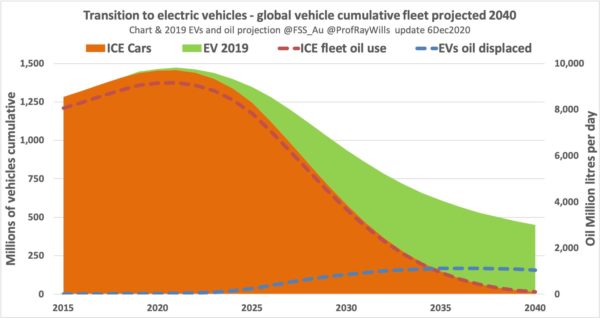

Today, the global electric vehicle fleet is believed to be more than 10 million. According to EV Volumes, a EV sales world database, sales of battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEV) rose from 2.26 million for 2019, to 3.24 million in 2020.

These numbers definitively dwarfs hydrogen fuel cell vehicle fleets, which is in the tens of thousands. In a direct sense today, there are simply more EVs being made, which means it’s easier, it’s cheaper, there’s more of a market for them. Wright’s Law is on EVs’ side.

Professor Ray Wills

So, is it possible for hydrogen to shoot out from behind? Technically, yes, Professor Wills says. But it would need a great push, nothing short of a miraculous invention that could double hydrogen’s efficiency would make it real competitor. Does that seem probable? “Not in the next 5 years.” Which is the timeline the Future Smart Strategies’ MD says hydrogen has to stake its claim before batteries consolidate their position.

The other thing that could see hydrogen take off though is if lithium batteries don’t perform. That is, if their prices and the battery densities for range don’t meet consumer needs. Given the rapid progress batteries have seen in the last decade, however, Professor Wills gives little weight to the scenario.

Why hydrogen has received the hype it has is because, Professor Wills says, oil and gas companies can no longer ignore that they need to move into the renewable game. They’re sticking to something they know – gas – although, as Professor Wills notes, hydrogen is a very different molecule to the gases the industry customarily deals in.

This echoes the sentiments of Smart Energy Council’s CEO John Grimes, who believes fossil fuel companies see hydrogen as a lifeline. Which is why the Council is vehement about finalising its Zero Carbon Scheme to certify green hydrogen as a matter of top priority.

Professor Wills, however, doesn’t quite share the Council’s expectation of a ‘global wave.’ Which is not to say he sees no role for hydrogen, specifically green hydrogen, in the future, but rather that he thinks the fuel will remain a straggler, unable to break out from behind batteries’ shadow.

Another factor is the issue of infrastructure. While it’s touted that hydrogen will be easier to roll out than EV charging stations, since we already have petrol stations dotting our streets, the tanks, hoses and ancillary infrastructure still needs to be built into those sites. So as it stands, Professor Wills says electric charging stations are also winning the infrastructure battle. “Could be overturned? Yes, if someone were to pour money at it.”

Government funds are still the driving force behind installing hydrogen infrastructure. EV charging station infrastructure, on the other hand, is already being competitively installed. “It just adds a layer to the advantage.”

Professor Ray Wills

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

Folks:

The economic arguments made above ignore some very relevant facts about the physical world. Lithium batteries have energy density a bit less than 1 MJ/kg. This is tolerable for automobiles but becomes prohibitively heavy for large trucks. A big truck would end up being about 30-40% batteries by weight, severely impacting its freight capacity (which is what the owner gets paid for). Hydrogen itself has an energy density of around 120 MJ/kg, but when stored as a compressed gas gives up a lot of this advantage. Nevertheless, you still end up with roughly 7 MJ/kg energy density. This is the difference between a practical large truck and a silly one. (For reference, fossil fuels are about 40 MJ/kg, but internal combustion engines are much less efficient than batteries or fuel cells, so the effective density is closer to 15-20 MJ/kg.)

What is correct to say is that the small-vehicle market will probably be served by lithium batteries, while heavy vehicles will use compressed hydrogen, unless a better means of storage is found. Liquid hydrogen achieves much higher energy density (around 50 MJ/kg) but is complex and expensive to create, handle, and store. It might be used in aircraft in the future.

Individual mobility by an own car will stay.

Globally every ecar needs its own charging station overnight, when the sun doesn’t shine. With a one familyhouse there is enough space. Public charging stations, for every car, plus overland stations, unaffordable.

Think of cables in Kairo, Lagos …

Hydrogen stations in container size are flexible to be placed everywhere.

Most imortant of a hydrogen economy:

A systemic electrical blackout is impossible, because hydrogen will be stored decentral, everywhere, to produce one’s own electricity.

So how does the professor explain the co-existence of petrol and diesel cars? Is it not because they each have significant niches in which one dominates over the other? It seems probable to me that hydrogen fuel cells will have an advantage in long-distance shipping, which is an enormous market, big enough to drive scale and innovation. And therefore there is likely to be contested space, perhaps in long-distance trucking, trains, aviation, back-up systems, etc.

Lithium Ion Batteries DONOT resolve the Pollution dilemma… they just replace Air Pollution from Fossil Fuel vehicles to Solid Waste… similar to, but not 100,000+ years long, nuclear waste…

Hydrogen is great… if only it was not explosive… already it has shutdown the LTA (Lighter Than Air) Cross-Atlantic Travel in 1931 with the Hindenburg Disaster / Blow Up…. and has raised a huge red flag for mobile applications (Vehicles, Buses, Ships.. to a certain extent…. and aircraft).

Ammonia from Nitrogen and Hydrogen appears possible if the NOx “problem” can be resolved…

Compressed Air Vehicles (CAV) have none of the above inherent drawbacks. Like Solar Energy… Air is Abundant, Pollution Free and Sustainable. The lower “Efficiency” can be readily offset by Recovery of the Heat of Compression …. and potentially…. just regular Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) Vehicles can be converted from Fossil Fuels to CA… with or without modifications and of course space for CA Cylinders…. below (or elsewhere) the floor….

Just as The Auto Industry “missed” the demand for high efficiency and smaller cars in the 1970’s, then again with Electric Batteries in 2000+, have now failed to recognize CA as the ONLY SAFE SOLUTION to restore the Environment by either converting ICE Engines they manufacture in hundreds of millions annually throughout the globe… or creating new CA Drives….

The question is: how will battery technology even do in large-scale transportation that doesn’t have easy access to charging stations (and they need relatively fast charging speed) like intercontinental flight aircraft or cargo shipping…