Australia’s solar industry has been singularly silent on the allegations of forced labour in the solar supply chain. The subject of steady global attention over the last few months, it is being alleged that forced labour among China’s Uyghur population, a Muslim-minority, is being used to produce polysilicon, the primary feedstock in the production of crystalline silicon solar modules.

China dominates the global supply of polysilicon, half of which originates from the Xinjiang region – an area that has been linked to problematic state-run labour programs. The region also has very cheap coal, which is also used to power energy-intensive polysilicon production.

China has strenuously denied the allegations, suggesting the accusations are an attempt by rivals to sabotage the country.

Unsurprisingly, the goings on in the Xinjiang region, and particularly in its polysilicon factories, are veiled by secrecy, with information very hard to come by. Nonetheless, the murky working conditions in Xinjiang, at times surely mixed with the desire to be less dependent on Chinese PV supplies, has proven reason enough for some governments and solar companies to begin taking steps to shift the supply chains.

Global outcry

The United States, European Union, United Kingdom and Canada have all put new sanctions on China over alleged human-rights abuses relating to its Uyghur population. The U.S. has already banned imports of cotton and tomatoes from the region, and it is suspected polysilicon may be next. Dutch political parties have brought the forced labour issue to parliament, while the European Commission is working on due diligence legislation and is expected to bring in new rules around importing products that may be linked to severe human rights violations.

No such stir can be seen here in Australia.

Australia–China interconnection

Australia’s solar industry is overwhelmingly reliant on China. And around 80% of solar panels installed in Australia are sourced from China, according to the Clean Energy Regulator. As John Grimes, Chief Executive of the Smart Energy Council, notes, the Australian solar industry interconnection with the country runs deep and has many tendrils.

“There’s been such deep engagement, right back to the 1970s and 80s when the young Chinese students here were studying at UNSW, the whole formation of the industry and the engagement between the two sides ever since, including a lot of research that’s happening in Australian institutions and being commercialised in China,” Grimes told pv magazine Australia.

In fact, he sees the solar industry as a beacon of hope in our increasingly tense relations with the country.

Grimes said it is imperative Australia approaches the forced labour allegations with a “level head.”

“In a heightened political atmosphere, the opportunities to make accusations without supporting information is very high,” he said.

“I have not seen direct evidence. I’ve seen a lot of assertions, but I haven’t seen direct evidence that there forced or slave labour is involved.”

“We don’t discount that [forced labour] is a possibility but ultimately there needs to be a level of credibility and provenience.”

Many governments and solar industry groups do not seem to share Grimes’ reservations. Media outlet Bloomberg claims when its reporters visited the Xinjiang region, they were trailed by Chinese officials, who obstructed their attempts to speak to locals and deleted their photos.

Grimes takes a cautious approach: “I just think we need to proceed judiciously, I think we need to proceed with cool head, but ultimately if there were credible evidence that was tabled, then that would have serious implications. And I think we as an industry, as an industry peak body, would be obliged to act on that.”

Australia’s peak industry body, the Clean Energy Council, told pv magazine Australia that it had established the Risks of Modern Slavery Working Group last year. “The working group is a platform for our members to share best-practice across the clean energy sector in identifying and reducing the risks of forced labour in the supply chain,” a spokesperson for the council said.

The Council did not go into details on if the working group had identified any particular risks or taken subsequent actions. It did, however, note that the Customs Amendment Bill 2020 (Banning Goods Produced by Uyghur Forced Labour) is the subject of the inquiry by the Senate Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Legislation Committee currently.

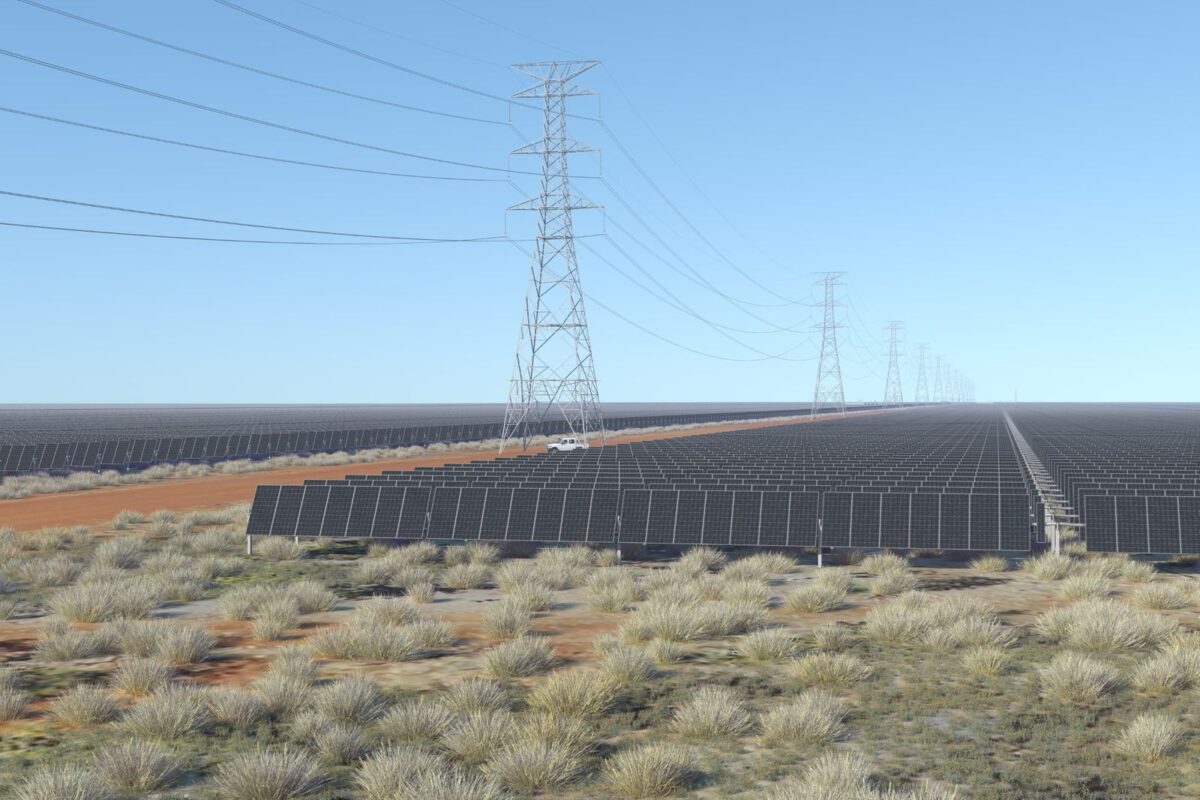

The cost of a supply chain shift

What the cost would be of shifting supply chains, Grimes said, is the “key critical” question. “That is ultimately not a question that I think the Smart Energy Council can resolve.”

“In relation to shifting supply chains – maybe that is going to ultimately be the answer. And maybe these are commercial questions for the companies involved.”

Grimes also noted the shift in supply chain could present an opportunity for Australia. The Australian Council of Trade Unions last week made a similar proposal. It has notably been one of the loudest groups to come out against the allegations, with ACTU President Michele O’Neil telling the ABC: “The treatment of Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities in China, particularly in the Xinjiang region is known to involve human trafficking and forced labour… the federal government and businesses must take immediate action to ensure they are not complicit or profiting from forced labour in Xinjiang or anywhere else in the world.”

O’Neil urged the federal government to invest in solar panel manufacturing in Australia (South Australia is home to one such facility, the country’s lone solar manufacturer). She says this would both reduce both Australia’s involvement in forced labour overseas and create jobs.

“In my view, a succession of Australia politicians should be horsewhipped for not seizing the commercial opportunity of that great innovation that happened here in Australia. It’s because we have this mindset that we don’t manufacture things in Australia and it’s way too expensive, and I think that’s completely not true,” Grimes said of the possibility of moving polysilicon production onshore.

“Certainly silica is extremely widely available globally. Australia does produce some of the highest grade silica in the world.”

Currently, Australia does not produce polysilicon. Both the United States and Europe do though, with their combined output amounting to around a quarter of the global demand. Groups and governments in those regions are advocating supply chains turn to these domestic sources to meet demand.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

Wake up Australia, china is not a moral country with human interests in mind, it runs on slavery and financial warfare all over the world.

The UN is a paper tiger fed by all the governments who are being blackmailed by china.