“PV power output is directly driven by meteorological conditions, and its drivers are likely to change in the future.” This statement, a few pages into a just published paper by researchers at the University of New South Wales seems obvious, but its implications as temperatures rise and weather patterns alter due to climate change will inform our expectations of solar output to 2079 and beyond.

The conclusions reached by the paper, Estimations of future changes in photovoltaic potential in Australia due to climate change provide insights into where solar farms could best be located as this century progresses; what solar researchers and manufacturers should be selecting for — performance at higher temperatures — in future cell technologies; and together with a companion paper on wind resource under climate change, published in 2018, they have implications for the siting of hybrid solar and wind generation that is expected to fuel Australia’s touted future hydrogen economy.

Since solar PV has become a vital pillar of the world’s transition to renewable energy, it’s essential that researchers are provided license to look up and beyond the immediate and very pressing horizon, to ensure PV development is following a reliable, sustainable, investable path.

This is the first study to use high-resolution regional climate projections in Australia to forecast changes in PV potential due to variations in shortwave downwelling radiation, temperature and wind speed; and the first ever to consider the additional impact of changes in cell temperatures.

Global temperature rises mean a hotter operating environment for solar cells

Shukla Poddar, PhD student at the UNSW School of Photovoltaic Energy and Engineering (SPREE) and lead author on the paper told pv magazine Australia that the most surprising outcome of this research “is the cell temperature effect”.

In other words, it’s obvious that changes in irradiation might cause increases or decreases in solar PV output in the decades-distant future, but in fact ever-increasing ambient temperatures implicit in global warming will also reduce cell efficiency and likely accelerate degradation of solar cells so that their output over time will further decrease, as will their risk of failure.

Preparing for performance under a worst-case scenario

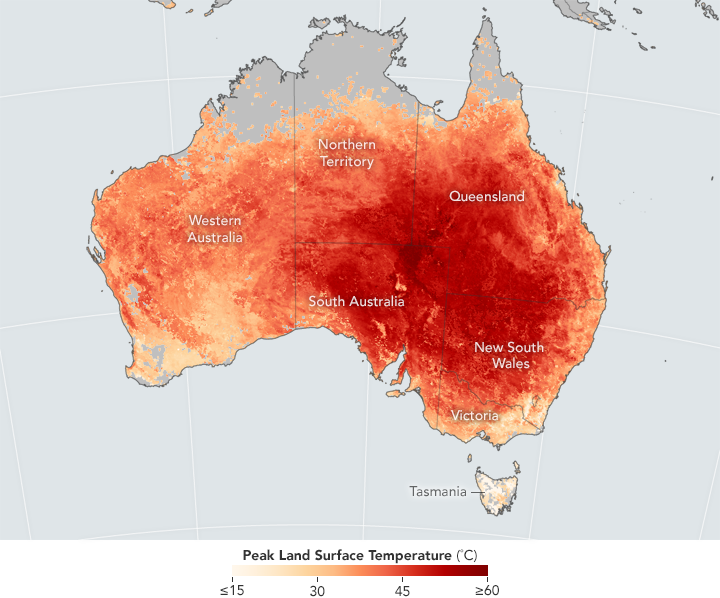

As UNSW Scientia Professor Martin Green has famously said, “Solar cells would prefer to be operating in a fridge”. Instead, their operating environment is typically hot, and becoming relentlessly hotter.

Poddar and co-authors have measured the effect on polysilicon solar cells of temperature rises under a high emissions scenario that projects warming of 3.4 degrees Celsius by 2100.

It’s not that the researchers are pessimists — far from it. But high-resolution climate simulations available from the New South Wales/Australian Capital Territory Regional Climate Modelling (NARCliM) project used the high-emissions A2 scenario, and the previous study into wind resource by one of Poddar’s co-authors, Jason Evans had also used the NARCliM data. Using the same data, ensures the two studies are relatable, to give an overall picture of how Australia’s renewable resources will fare under climate change.

A third co-author, Dr Merlinde Kay, tells pv magazine Australia, “When you’re thinking about this work, it serves as a risk management strategy.

“It describes what could happen in the future and gives people enough time to prepare for what the most extreme outcome could be.”

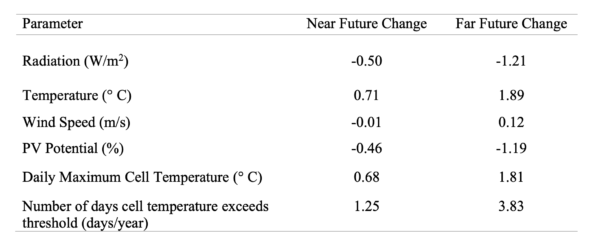

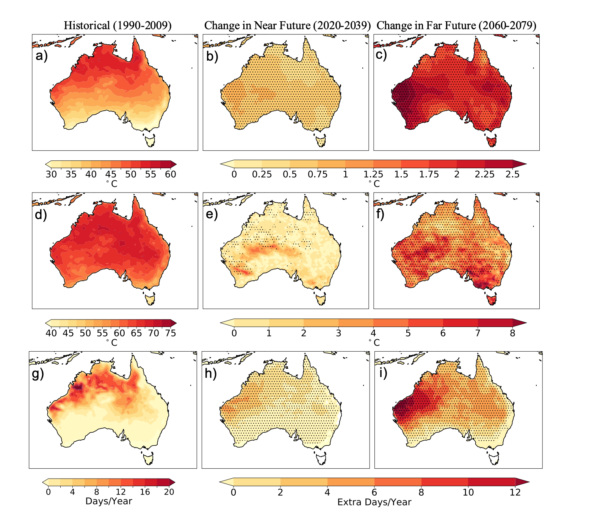

number of days cell temperature exceeds the threshold for minimum 15% efficiency loss averaged over Australia for the near future (2020-2039) and far future period (2060-2079) obtained with respect to the historical period (1990-2009).

UNSW SPREE

PV potential declines as meteorological conditions change

The paper found that PV potential across Australia is projected to decline during the 21st century: during both a near-future period, defined by NARCliM as 2020-2039 (which has already begun), and the NARCliM-defined far-future period of 2040-2079.

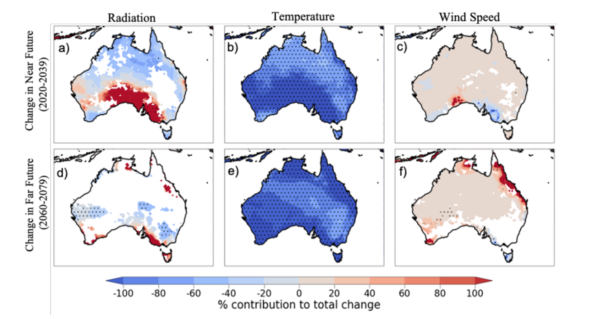

However, some geographies will experience more pronounced changes due to evolving weather patterns under climate change: “The maximum decline in PV power generation is expected to occur in Northern Australia during the near-future period and South-East Australia during the far future period,” say the authors, with the greatest decreases due to elevated temperatures, and the next most significant effect due to a projected decline in radiation.

There will be more days each year when PV power generation is significantly less than the rated generation capacity.

UNSW SPREE

Cell-cooling technologies being developed by Prof. Martin Green

These findings make Professor Martin Green’s research into technologies that will lower the operating temperature of solar cells even more urgent.

Green’s recent desktop study into the effectiveness of cooling cells by various methods was carried out in collaboration with 5B, the suppliers of prefabricated, “foldout” arrays of solar panels to the world’s biggest solar PV and battery storage project known as Sun Cable. Some components of the project are scheduled to commence construction in the Northern Territory’s Barkly region in late 2023, and it is expected to achieve full capacity — between 17 GW and 20 GW of solar generation, and 36-42 GWh of storage — in late 2028. That is, the project will be operating within the near-future period defined by the UNSW study.

“For a researcher, it would be an amazing case study to measure what occurs there,” says Kay.

5B itself closely monitors its innovative ground-mounted Maverick system, verifying performance under different conditions. It has a reciprocal research arrangement with UNSW, sharing data with UNSW and is now participating in experimental research to lower field operating temperatures of solar cells, which will help mitigate the effects of climate change.

relative cell efficiency losses over Australia. (Stippling indicates a significant change.)

UNSW SPREE

Concentrating the fields of solar cell research to meet future conditions

Like recent groundbreaking UNSW research into the sustainability of silver, indium and bismuth use in the solar industry as it moves toward multi-terrawatt production and installation, the Estimation of future changes in PV potential… paper could also serve to narrow the field for future viable PV technologies — specifically those that deliver efficiency at high temperatures.

Poddar says that cadmium telluride and other thin-film technologies look promising.

Such cell structures are already being deployed by some solar manufacturers: for example, US solar module manufacturer, First Solar, this year announced that its Series 6 CuRe panels have achieved what it claims to be the lowest degradation rate in the PV industry, and can operate at high efficiency, even when cell temperatures reach 85 degrees Celsius.

Overall, this latest future-focused UNSW research hopes to “help in the assessment of resources and site allocation before deployment of large-scale projects in Australia”, says the paper.

And, it concludes, “It is highly recommended to incorporate a detailed intercomparison of various PV technologies in future for the areas expecting a high temperature rise due to global warming” — appropriate PV material selection will ensure maximum power generation in future heated climate scenarios.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

1 comment

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.