With the findings from the review of Australia’s carbon credit scheme led by former chief scientist Professor Ian Chubb due by December 31, the foundations on which two of Australia’s core climate policies rest are in a kind of purgatory.

“How radical Chubb’s assessment of what needs to change within the carbon credit market will really impact whether we see a revolutionisation of the Australian carbon credit market or maybe just some tinkering around the edges,” Emissions Removal Manager at the Australian National University’s Below Zero, Caitlyn Baljak, tells pv magazine magazine.

“Because this market is so convoluted,” she adds, understanding exactly where the issues are and how they are connected is difficult. “It’s not easy for the everyday person to see what’s happening,” she notes.

Given the policies could not only make or break Australia’s climate achievements, but are also attracting the likes of Genex Power co-founder Simon Kidston, who on Monday launched his new carbon development business Permagen – likening the move into Australia’s burgeoning carbon market to his play with Genex back in 2013 when renewables were still in their infancy, it’s worth understanding where the issues lay and how they might be addressed.

Image: Genex Power/Wikimedia Commons

Scheme overview

In the simplest terms, one Australian carbon credit unit, or ACCU, is supposed to represent one tonne of carbon dioxide abated. Emitters can then buy the credits and say their emissions have been cancelled out, or brought to a net zero.

This offset system has many critics, which we’ll get to later, but the drama that unfolded this year surrounding Australia’s carbon credits basically boiled down to the claim that one credit currently does not represent one tonne of abatement, and very few of the projects making money for creating credits actually made real, additional abatements.

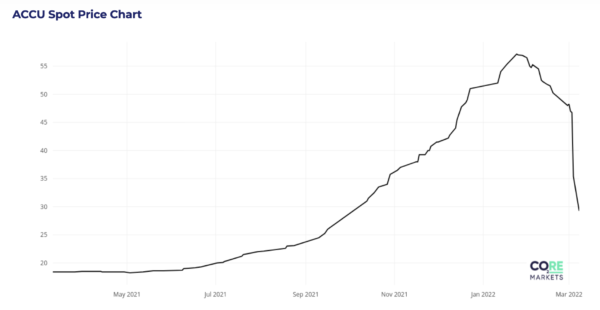

Core Markets

This is a major problem for Australia’s Safeguard Mechanism, a scheme which makes it compulsory for Australia’s biggest emitters – 215 facilities producing more than 100,000 tonnes of greenhouse gases a year – to offset their emissions. These facilities offset emissions using Australian carbon credits, so if that scheme is bogus so too is the foundation on which the Safety Mechanism rests.

This is a major problem for the recently elected Albanese Labor government, which campaigned on reducing Australia’s emissions 43% by 2030. To reach that goal, Labor simply has to to make these long running schemes work properly.

Australian carbon credits

The saga around the integrity of Australia’s cornerstone climate schemes begun in earnest with whistleblowing from Australian National University professor Andrew Macintosh, the former head of the committee responsible for ensuring the integrity of the Emissions Reduction Fund under which carbon credits are made, who claimed the $4.5 billion scheme effectively amounted to taxpayers’ money being spent on fake climate action.

For Macintosh, in their current form Australian carbon credits amount to “fraud.”

“The available data suggests 70 to 80% of the ACCUs issued to these projects are devoid of integrity – they do not represent real and additional abatement,” Professor Macintosh said at the time.

This was denied by the Clean Energy Regulator, the government body that runs the scheme, but the new Albanese government nonetheless opted to launch an independent review.

Many players from within the industry, including participants in the carbon credit scheme, applauded the step – though of course the rejoicing was far from unanimous.

Looking at the review submissions, which have now been made public, organisational lines tend to follow the expected routes with big emitters who buy credits insisting they’ve done their due diligence and companies behind carbon credit projects insisting their methods are scientifically sound.

On the other side, submissions from organisations like ANU Institute for Climate, Energy & Disaster Solutions, advocate for a complete overhaul of both the scheme’s governance and methodology, pointing out with the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism slated for implementation in 2026 and similar policies looming elsewhere, Australia can either get real or haemorrhage in future economies.

The core carbon credit criticisms

As ANU’s Baljak names it, the “biggest fish” seen to be jeopardising Australia’s carbon credit scheme are issues of governance of the umbrella Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF) and three of the carbon abatement methodologies:

- Human-induced regeneration (HIR) method

- Avoided deforestation

- Landfill gas

While there are a total 38 methodologies that can be used to create carbon credits, the above three account for the vast majority of credits and have come under the most fierce scrutiny.

Human-induced regeneration (HIR)

In short, this method involves allowing forest and native vegetation to grow on land previously been used for livestock grazing, growing non-native plants or where for whatever reason human-actives were seen to be suppressing natural regrowth.

While allowing forests to regenerate is widely accepted as a good thing, the issue with this method is the “human-induced” claim. In short, critics say forest regrowth usually has little to do with less grazing from livestock or impacts of feral animals – the two main ‘human induced’ regeneration approaches – and instead rests of natural rainfall.

A recent paper from Professor MacIntosh and others from ANU and the University of New South Wales, found basically all of the HIR projects are located in semi-arid and arid areas that have never even been comprehensively cleared.

The premise humans are suppressing growth, and should earn money for changing their ways, is fatally flawed and needs to be fundamentally revised, critics say.

Avoided deforestation

Again, the criticism here is not that avoiding deforestation is a bad thing, but rather that the government is paying people to not clear land they never actually intended to clear.

Research from the Australia Institute found credits awarded for ‘avoided deforestation’ were issued based on land clearing rates between 751% and 12,804% higher than anything seen on the ground.

“The method totally overestimates the rate at which landholders would be clearing, and so you’re basically creating fraudulent ACCUs within the system unfortunately because of that misestimation of what the reality and the counterfactual would be,” Baljak says.

Coming back to the method’s intention, it does echo back to concerns state and territory governments do, or have in the past done, a poor job of protecting native forests. While Baljak says lower governments still don’t have enough checks and balances in place to adequately protect forests, her institute still believes it is best to revoke this method entirely.

Landfill gas

This method basically boils down to companies capturing the gas from Australia’s landfill sites, mostly methane, and combusting it to create the less potent carbon dioxide.

While the landfill gas is among the best at actually counting concrete emissions (much better than say the assumed carbon abatement from a tree that may or may not grow), the issue here comes down to questions of baselines and additionality.

As the method evolved, different projects in scheme have had different baselines. Those who entered early were given low baselines – “some as low as 0%,” Baljak says.

“Unfortunately the way it has worked out is that it tends to be those bigger players who have those lower baselines – who don’t really need that incentive – and those smaller players, where that benefit really comes into play, that have been stuck with the higher baselines, and it just makes it more difficult for them to compete with other landfill gas producers,” Baljak says.

This has made the footing for players in the game majorly unequal and has resulted in landfill gas companies welcoming the review.

The other issue here is that landfill gas companies can also participate in other schemes like claiming Large-scale Certificates, the subsidy given for supplying renewable energy to grid. They therefore already have a financial incentive to capture landfill gas and (instead of flaring) using gensets to turn that gas into energy for the grid, so some say the carbon credit incentive amounts to a form of doubling up.

Cost of reform

Given the issues with Australia’s carbon credit scheme are pretty foundational, it begs the question of how much such reform will cost. According to Baljak, the biggest expense is always setting up the regulator. Luckily, the Clean Energy Regulator (CER) exists already, so that’s done. There are many questions about CER’s governance of the scheme going forward, but clearly the federal organisation will be involved in oversight into the future.

Baljak doesn’t think the additional cost will be that significant going forward, and that any cost would well and truly be offset by the better price a high-integrity carbon credit can collect.

“One of the biggest things that you can do for integrity of the scheme, even if it does end up costing slightly more in the scheme of things, is that demonstrated evidence through direct measurement that the carbon that you say is in the ground is in the ground,” she says.

“Ultimately if you have a higher integrity scheme and buyers are willing to pay more for those units, that will more than cover the additional cost of the measuring and monitoring through that consumer confidence which translates to a higher purchase price for the carbon.”

Energy analytics firm RepuTex has forecast Australian carbon credits could increase from $33 (USD 22.50) each now to as high as $110 by 2032. Baljak says some of this high price should

be transferred to regulator as the body responsible for ensuring integrity, rather than only to the landholders and carbon credit aggregators.

The Safeguard Mechanism

Described by the Saturday Paper as the “most important climate policy you’ve never heard of,” Australia’s Safeguard Mechanism is supposed to drive down the emissions of Australia’s biggest polluters, those emitting more than 100,000 tonnes of greenhouse gases per year.

Introduced by the former Coalition government, the policy basically works on the principle that each polluting facility is given a “baseline” (not to be confused with a cap) to dictate how much it is allowed to emit. If the facility goes over that baseline, it is mandated to buy carbon credits to “offset” those emissions.

Since the “offsetting” component of this scheme largely relies on Australian carbon credits, its usefulness really rests on whether the government is able to sort out the integrity issues outlined above.

Beyond that though, the Safeguard Mechanism has a plethora of its own issues. Around 215 of Australia’s biggest climate polluters are subject to the mechanism, but since the scheme was brought in in 2016, the emissions from those facilities have actually gone up 7%, or, in carbon emission terms, nine million tonnes. Emissions from some gas extraction facilities went up a massive 20% in that time, analysis from the Australian Conservation Fund (ACF) found.

The core issue here is the “baselines” given by the former government were so generous they were entirely useless. The ACF also found that many of the facilities captured by the Safeguard Mechanisms had baselines double their estimated emissions. “In one instance, a facility had a baseline set twenty times higher than its predicted annual emissions,” the ACF said.

Journalist Mike Seccombe used a brilliant analogy for the scheme, describing it like “a limbo dance where the bar was set so high that participants did not have to lower themselves to get under it.”

Where that review is at

The current review of this scheme is examining this baseline question, as well as which new sectors and facilities should be included.

The review is pretty far along, with a bill looking to amend the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Act 2007 (NGER Act) and Australian National Registry of Emissions Units Act 2011 to establish Safeguard Mechanism Credits, covering how credits are issued, purchased, and included in the Australian National Registry of Emissions Units, introduced to the lower house of Parliament on November 30.

An exposure draft of the new Safeguard Mechanism Rule is also imminent, with the government closing the stakeholder consultation period on the draft on October 28. The new rules are slated for effect July 2023, provided they pass both houses of Parliament.

In a recent look at the Safeguard Mechanism reforms, thinktank Climate Energy Finance director, Tim Buckley, noted that what is really need is legislation rather than regulation. That is, the market parameters need to be set in a meaningful way for the scheme to have any hope.

It’s also worth noting the whole Safeguard Mechanism premise has a lot of critics – the main thrust of that argument is that ‘offsetting’ instead of actual emissions reductions is a silly path that amounts to more threading water on climate than actual forward movement.

Another facet of this whole reform saga, Baljak points out, is that if Ian Chubb does come out with recommendations that meaningfully shift how Australian carbon credits are created – ensuring only high integrity, meaningful abatement projects are awarded credits – that will dramatically limit the supply of carbon credits. That, in turn, would mean there are far fewer credits on the market for facilities captured by the Safeguard Mechanism to buy.

This demand massively outstripping supply would place a huge stress on the market. “If the Chubb review comes along and says, ‘We’re going to fix these integrity problems’, credit supply is going to plummet and, as a consequence, prices go through the roof,” Baljak says.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.