The Commonwealth government’s primary climate policy, the Emissions Reduction Fund, which underpins its carbon credit scheme, has this week been decimated, with an onslaught of criticism and alarming accusations from its own participants, its former chair and third parties.

Former chair blows the whistle

On Thursday, Professor Andrew Macintosh, chair of the Integrity Committee of the Emissions Reduction Fund for six-and-a-half years until 2020, and Associate Dean at the Australian National University’s (ANU) College of Law, called the fund and the carbon credits generated within a “fraud.”

“The available data suggests 70 to 80% of the ACCUs issued to these projects are devoid of integrity – they do not represent real and additional abatement,” Professor Macintosh said.

“Unfortunately, Australia’s carbon market currently suffers from a distinct lack of environmental integrity. All of the major emission reduction methods have serious integrity issues, either in their design or the way they are being administered,” he added.

Scheme referred to the Auditor General

The revelation prompted federal Greens leader, MP Adam Bandt, to refer the allegations to Australia’s Auditor General, calling for an independent inquiry into the claims.

“When the former head of the government’s Emissions Reduction Assurance Committee reveals that the carbon credits scheme is ‘largely a scam’, we need an open transparent inquiry with powers to get to the bottom of it,” Bandt said.

“This is a critical issue. Both the Morrison Government and Labor are claiming to take climate seriously while planning to open up 114 new coal and gas projects, relying on permits and offsets to cover up their duplicity. If carbon credits are fraudulent too, then Australia will definitely blow its climate targets.”

Australia institute points to potential corruption

Among this chorus, thinktank the Australia Institute has also published findings from Freedom of Information documents this week. It says the documents show that when designing the Emissions Reduction Fund, which includes come carbon capture and storage methods among its 38 project “methods” or types, the Commonwealth’s Clean Energy Regulator consulted “almost exclusively” with fossil fuel companies and big emitters.

In a statement, the federal energy and emissions reduction minister Angus Taylors defended the scheme, implying the Australia Institute’s report was politically motivated, and questioning why Andrew Macintosh had not raised the alarm while he was chairing the fund’s integrity commission.

Carbon market participants write open letter

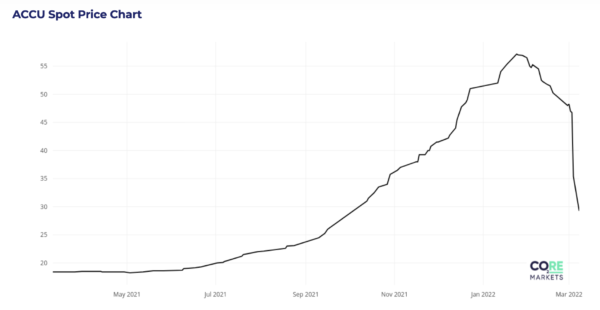

This is all unfolding on the backdrop of Australia’s carbon credit units (ACCU) prices plunging, following Taylor’s announcement he would give carbon credit creators the option of stepping away from their government contracts on March 4.

Core Markets

On Wednesday, 15 of the most significant carbon market participants sent an open letter to Taylor calling for a deferral of changes to the fund until midyear. It said Taylor’s announcement was made “without consultation or warning” to industry.

The signatories are calling for changes – like the release clause option to be deferred until July 1 so land managers and the wider carbon farming industry can properly prepare. “There’s quite a lot of administration for this process to be done properly and for people to make informed decisions about whether they should deliver to the government or choose to sell,” Climate Friendly CEO Skye Glenday told pv magazine Australia.

“Right now, there’s a live exit window with no actual operational rules,” she added. “That’s just creating a lot of uncertainly for all participants.”

By putting the voluntary carbon credit market into free fall, Glenday said the minister’s decision had disincentivised new carbon abatement projects. Australia is home to around 77,000 agricultural properties, but the scheme has only 890 projects land sector projects – not even reaching 1% of those landholders.

The market prices being collected for these projects will certainly not be helped by the accusation that the majority of the abatement projects are not scientifically credible. Climate Friendly says the six methods of projects with which it works are science based.

Carbon credit market flooded

Compounding this, is the potential flooding of the market of carbon credits should project owners opt to take up Taylor’s option of stepping away from their government contracts.

Last year, for instance, the federal government purchased around 12 million tonnes of carbon abatement. This could theoretically now enter the voluntary market, even though the Clean Energy Regulator’s quarterly report released last Friday posited that there is only demand in the voluntary market for about one million tonnes of abatement projects.

Earlier this week, research company RepuTex released analysis saying the minister’s decision could increase the number of carbon credits on the voluntary market by 7 million during the June quarter alone, and by as many as 112 million by 2033.

Such numbers would near guarantee the price of carbon credits would remain suppressed in Australia, with RepuTex executive director saying the market now had a “mountain of supply to overcome.”

Low prices for ACCUs are primarily (perhaps solely) beneficial for big emitters, because it gives them access to cheap, abundant supply of carbon credits with which they can use to “offset” their emissions.

Higher prices on ACCUs, on the other hard, would be beneficial to carbon farmers, and also makes carbon farming a more attractive option in Australia.

Taylor has said the contract release clause will stimulate more abatement projects, though it remains unclear why an oversupply would stimulate a surge in demand when economically the mechanism is used to drive down prices.

“One of our suggestions was that they only release a portion of the contracts that is aligned with the demand in the marketplace based on analytics,” Glenday said.

Who holds Emissions Reduction Fund contracts

According to the public carbon abatement register, around half of the government’s contracts from land sector carbon abatement projects are held by large aggregators like Greencollar and AgriProve, both of which have signalled support for Taylor’s decision.

The other half are held directly by landowners, with whom Climate Friendly says it works to support their land sector projects.

Part of the issue is that while landholders have contracts with the government, they often only sell some of the resulting ACCUs to it, opting to save a portion to sell on the voluntary market. So for many of these landholders, they would have been better off under that route – delivering some to the government at, say, a fixed price of $12 an ACCU, and then collecting a higher voluntary carbon price for the remaining ACCUs.

Before Taylor announced the changes, ACCUs were worth $50. Since March 4, ACCUs have lost almost half of their value, with prices now sitting around $30.

On Wednesday, Wood Mackenzie said the global prices of carbon needed to rise seven fold to properly facilitate and incentivise low emissions technology development and adoption. It expects the “global carbon price to rise seven-fold from an average of US$25 per tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent today to US$175/t CO2e by 2050 in developed economies and US$127/t CO2e in emerging economies.”

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.