From: The Conversation

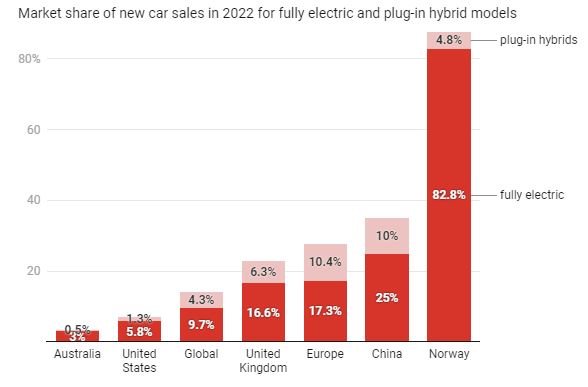

The world leader in electric vehicle (EV) uptake is Norway, where 87.6% of new cars (including 4.8% plug-in hybrids) are electric. Australia’s figure is also far lower than in Europe (27.7%, including 10.4% plug-in hybrids), China (35%, 25% fully electric) or even the United States (7.1%, 5.8% fully electric).

However, even in Norway the proportion of cars on the road that are electric – although impressive compared to the rest of the world – is still only 20%. This difference reflects the time it takes to replace an existing fleet of internal combustion engine cars.

Why are sales so low in Australia?

Why has Australia done so badly? The overt hostility of the previous government to electric vehicles can’t have helped. Prime Minister Scott Morrison even claimed Labor wanted to “abolish the weekend” with its electric vehicle policy.

But the Morrison government has been gone for the better part of a year now and electric vehicle sales, while growing, remain very low.

The two core issues faced by Australians wanting to buy electric vehicles are affordability and lack of availability. Despite some recent modest price reductions, Teslas are priced out of reach of most private car buyers. They also face long delivery delays. Would-be buyers of many other brands face similar problems.

Australian governments have done little, if anything, to encourage the transition to electric vehicles. Almost uniquely among developed countries, Australia has neither a carbon price nor vehicle fuel-efficiency standards.

The Victorian state government even taxes electric and hybrid vehicles for their road use. South Australia had a similar tax, but has abolished it.

There have been a few positive measures, mostly at the state level. Although the federal government has legislated an exemption from fringe benefits tax, it offers no direct benefit to individual car buyers. The government’s development of a national EV strategy may lead to other initiatives.

But incentives don’t make much difference if it is impossible to buy a vehicle. Until recently, delivery delays could be explained as part of general COVID-related disruptions and restrictions introduced to control the pandemic.

But those restrictions are mostly gone now, and remaining supply disruptions haven’t stopped millions of European and Chinese buyers from getting behind the wheel.

Industry’s structure is a barrier

A critical problem is that the Australian retail motor industry has a structure designed for the 20th century, when a small number of locally made cars, powered by internal combustion engines, dominated the roads. Retailers, typically franchisees for one of the major manufacturers, provided not only a distribution channel, but highly profitable after-sales service.

With the end of Australian manufacturing, this no longer makes a lot of sense. The requirement to buy through an authorised dealer, like other systems of this kind, allows overseas producers to raise car prices for Australian consumers, with few offsetting benefits. They can also supply the market with fuel-inefficient models.

The problem is even worse for electric vehicles. Compared to vehicles with internal combustion engines, electric vehicles have many fewer moving parts and much less need for costly servicing.

The most important component, the battery, has an estimated life of up to 20 years. There’s no transmission, spark plugs, timing belt or air filter to worry about. Profits on all of these items enable car dealers to reduce the sticker price on fossil-fuelled vehicles, making them much easier to sell.

Electric vehicle maintenance costs are ~40% lower than those for internal combustion engine vehicles. And here are where the savings come from:

Source: https://t.co/d4WOcen7tu pic.twitter.com/U5jv8oaDMW

— Emil Dimanchev (@EmilDimanchev) June 15, 2021

Parallel importing is part of the solution

One step towards solving this problem would be to allow consumers to import new and used cars from overseas suppliers. This is known as “parallel importing”.

Consumers have already seen the benefits of parallel importing for items including books, music and a wide variety of consumer goods. In some cases, such as that of books, parallel importing can be done only by individual consumers; in others it is open to firms that wish to compete with existing distribution channels.

Australia is far behind the rest of the world in the transition from fossil-fuelled vehicles. To avoid falling further behind, we need to change the kinds of vehicles we import.

A fuel-efficiency standard would discourage the dirtiest of our current vehicles. While increasing the upfront sale price, it would save drivers money in the long run.

Parallel importing would increase competition in the market for new and used electric vehicles overnight. Manufacturers would have to reconsider their supply and pricing strategies for Australia.

Allowing independent importation would also promote the development of a skilled workforce to service the cars. It could even allow the development of local manufacturing of electric vehicle components.

Authors: , Professor, School of Economics, The University of Queensland; , Professor of Economics, Director of the Australian Institute for Business and Economics, The University of Queensland

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those held by pv magazine.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

The fuel excise of over 40cents per litre puts billions in the public purse. The end of ICE vehicles means the end of fuel excise income to the government. That might explain the lack of action to promote the changeover.

The inevitable and politically divisive solution is obviously road pricing. Removal of excise taxes earmarked for road construction and maintence and imposition of tolls on all roads, tunnels and bridges. Taxing electrical charging of vehicles would only work at commercial stations at but not at homes, businesses or on the vehicles themselves.