On Australia’s doorstep, a distinct energy narrative is unfolding. The wide-spread destruction of infrastructure by Indonesian militias in 1999 and prior has severely impeded Timor-Leste’s human and economic development for more than two decades.

Despite progress, a significant proportion of the country’s population continues to live in abject poverty. A lack of access to proper nutrition, basic sanitation, health services, safe drinking water, and reliable energy are still evident throughout the country.

Meanwhile, the country’s fledgling economy relies heavily on fleeting offshore oil and gas reserves – with one large untapped field in the Timor Sea at the centre of an international tug-of-war. Aware of the current climate of … climate (pun intended), the country’s President and former Nobel Peace Prize recipient, Jose Ramos-Horta has publicly stated that he would happily leave their fossil fuels under the seafloor if high-income nations increased foreign aid to support the country’s development.

Over seven days in the country our group met with 15 different stakeholders – from the president of the country’s petroleum authority, to the villagers who walk hours to load $5 on to their electricity accounts. We did this in order to understand the dynamics of how the energy transition is affecting one of our closest neighbours.

Image: Pell Center

About Timor-Leste

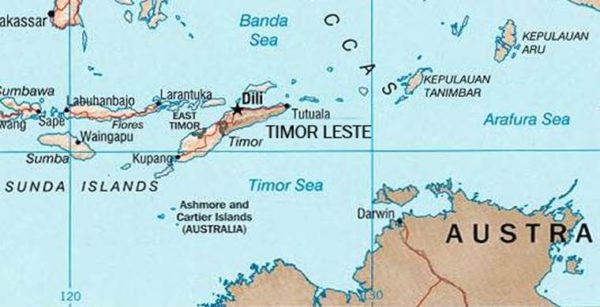

Timor-Leste (also known as East Timor) sits just an 80-minute flight from Darwin. Once a Portuguese colony in the 16th century, the territory remained under Portuguese rule until 1975, when it was occupied by Indonesian forces. The East Timorese resistance, led by the Revolutionary Front for an Independent East Timor (FRETILIN), fought against Indonesian rule for 24 years, during which time as many as 200,000 East Timorese were killed.

In 1999, a UN-supervised referendum was held in which its people voted overwhelmingly for independence. After the announcement of the results, pro-Indonesian militias engaged in a campaign of violence and mass destruction, resulting in the deaths of thousands, and the displacement of hundreds of thousands more. Some estimate that more than 80% of the country’s infrastructure was destroyed during this final act of carnage – including hospitals, water facilities and large parts of the country’s electricity network.

The eventual intervention of an international peacekeeping force helped restore order and pave the way for Timor-Leste’s independence. In 2002, the country officially declared independence and remains Asia’s newest sovereign state.

Today Timor-Leste has a population of 1.3 million with a median age of just 19.6 years. The Asian Development Bank reports that 41.8% of the country live below the national poverty line, and 22.6% of its employed population earn below USD 1.90 per day.

Don’t take a reliable electricity grid for granted

For me the most salient takeaway from the trip was the ubiquitous impact that a lack reliable electricity has on quality-of-life outcomes.

Our group (of relatively privileged Australians) became acutely aware of this upon spending two nights in homestays on the island of Atauro. The island’s diesel-fuelled electricity grid runs only from 8am to 12pm and then again from 2pm until 10pm. Our homestay families provided incredibly warm and generous hospitality, but unfortunately there was little they could do to ensure we could achieve a good night’s sleep. Many of the houses on the island are made of concrete and are unventilated – and a lack of electricity means that the very humid and hot conditions cannot be alleviated by fans or any other form of cooling.

But a couple of nights of restless sleep are a minor quibble to more pressing issues.

The island’s maritime police only have access to the main grid. When the grid is not running, the police station in the north cannot radio to the station on the south of the island as there is also no mobile phone reception. The main hospital for the island also does not have a working backup generator. If you’re in need of medical help on the island after 10pm, the doctors and nurses can only do their work under the light of their phone torches and without any medical equipment that requires electricity.

Back on the mainland, the country’s main electricity grid runs 24 hours a day, except when it doesn’t. Several locals in the mountain town of Maubisse explained that blackouts are common but especially during rain – perhaps the result of a poorly insulated distribution network. Power quality is also an issue. One hotel owner complained of six broken fridges as a result of voltage surges.

Electricity was free in most areas until last year, when the rollout of electrification increased and led the government to install power meters within homes and businesses. The system is prepaid. Residents provide their meter number with payment, and in return receive a code which they then punch into their power meter. Many locals do not have a bank account and some are without internet, which forces them to top-up their meters manually – one man we met walks two to three hours to the nearest town to purchase $5 worth of electricity every month.

Development and/or sustainability?

While its people struggle with access to energy, the country’s economy is reliant on it. The headline stat is that offshore oil and gas accounts for 90% of the country’s GDP.

The Bayu-Undan field in the Timor Sea is currently the government’s main source of revenue but is slowly winding down production. The Timor-Leste Petroleum Fund was established in 2005 as an attempt to provide a long-term source of revenue for the country after its reserves are fully depleted, intended to replicate the design of Norway’s sovereign wealth fund. The Petroleum Fund’s most recent report from September 2022 showed its balance to be $16.91b, down 11.79% year-on-year – stating that $404m was transferred out of the fund to finance the national budget in Q3 2022 alone.

The Greater Sunrise project is one of the country’s remaining untapped oil and gas fields. Estimated to contain over 5 trillion cubic feet of natural gas and 225 million barrels of condensate, it’s thought to have a $50b resource valuation. The project has been locked in a 20-year standoff between Timor-Leste and Australia because of debate over which country the pipeline should lead to and where the gas should be processed. Timor does not currently have the onshore refinery facilities for the project, but the biggest roadblock is a 3000-metre-deep trench (the ‘Timor Trough’) that sits in between the field and its shorelines. The trough poses a major engineering challenge for any pipeline that would lead to Timor’s south coast.

Our meeting with ANPM (the national petroleum authority) reiterated the Timorese desire to overcome these difficult engineering and commercial challenges in order to boost local jobs and broaden economic benefits. Until now, the prevailing view of their Australian counterparts is that a pipeline to Darwin is the only viable option. A floating LNG plant was a third option previously favoured by operator Woodside but that proposal has also not been pursued thus far.

image: ABC

Last September, the IMF warned that the country faced “the risk of a fiscal cliff” if the Greater Sunrise project was further delayed or if reforms to the country’s petroleum fund were not made. La’o Hamutuk – a Dili-based NGO we visited, monitors the country’s economic progress and also reported concerns over recent and planned withdrawals from the fund to underwrite subsequent budget announcements.

Another sunrise on the horizon

Several humanitarian organisations and other NGOs have funded small-scale solar projects to reduce some communities’ reliance on the electricity grid, and in some rural areas, have provided electricity access for the first time. However, a lack of capital and the skilled workforce needed are obvious barriers to a material uptake for residents and business owners to do so on their own accord.

Efforts are also being made to diversify the country’s economic pathways. Two industries with significant potential are tourism and coffee production. The country boasts a rich cultural heritage and unspoiled coral reefs, providing great opportunities for growth for international tourism. Its coffee industry is more mature on the other hand, and dates back to the colonial era when Portuguese settlers introduced coffee trees to the island. Not-for-profit cooperatives such as PARCIC Coffee are actively assisting family-owned coffee farms in processing and exporting their raw coffee beans to the Asian market.

The story of a resource-dependent economy attempting to progressively navigate away from mining fossil fuels might sound familiar to Australians. For Timor-Leste however, the consequences seem much more dire if done unsuccessfully.

Dan Lee thanks The University of Queensland, program director Dr Tony Heynen and Anastascio Madeira from Timor Unearthed without who the trip and subsequent learnings would not have been possible.

This article was originally published on WattClarity and republished here with permission

The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own, and do not necessarily reflect those held by pv magazine.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.