Federal Minister for Resources, Madeleine King, has released Australia’s Critical Minerals Strategy 2023–2030, an important document given Australia’s renewable energy superpower role seems to increasingly hinge on the sector.

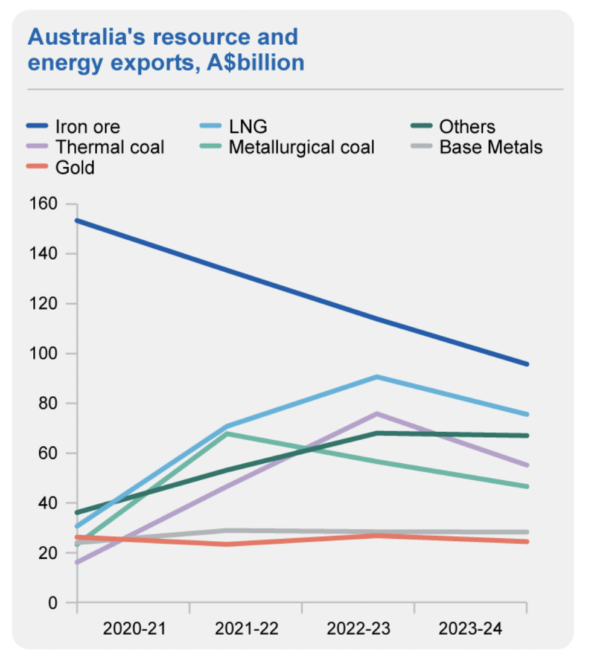

In many ways, the role is a natural fit for Australia – not only does it have “internationally significant critical minerals endowments,” as the government puts it, but it also has a highly developed mining industry and an established global reputation as a resources exporter.

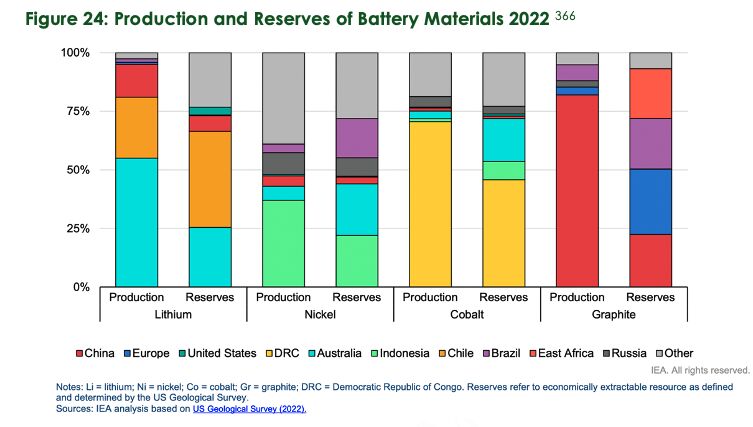

The key, as many in government and industry have long pointed out, is moving from exporting raw materials to actually bringing ‘value-added’ mineral and chemical processing operations onshore. It would seem a critical minerals strategy would tackle exactly these questions, but unfortunately very few practical proposals are included in the document.

Image: Australian government, under International Licence

CC BY 4.0

The main action in the strategy is $500 million (USD 340 million) for the Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility, specifically for projects in the critical minerals sector with a particular focus on downstream processing.

The Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility (NAIF) is like the Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC) in that the federal government provides it funding to hand out in various forms to projects it deems worthy of support. Unlike CEFC though, it doesn’t have a particular focus on energy or renewables, but supports a wide range of industries. As the name suggests, it focuses on projects within the north of Australia, including Queensland, the Northern Territory and north Western Australia.

(In separate news, the federal Greens party has said it will not support Labor’s broader plan to pump a total of $2 billion into NAIF without guardrails to ensure that it cannot be used to finance coal and gas.)

While this funding will directly support some projects, its scope is clearly limited. Sitting aside this, the government notes it plans to “establish the National Reconstruction Fund, which includes $1 billion for value-add in resources and $3 billion for renewables and low emissions technologies,” though no further detail is given here on how this specifically furthers critical minerals developments.

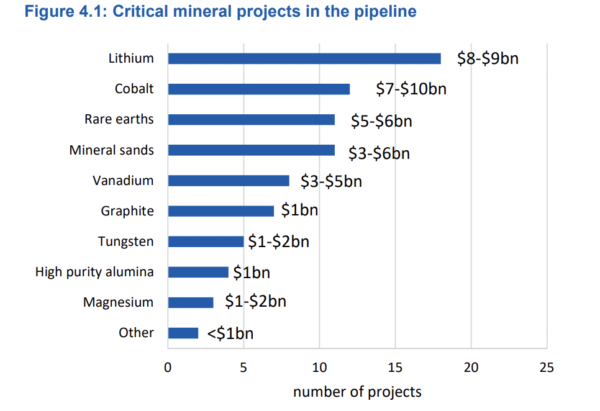

The strategy will also establish a process to update the nation’s critical minerals list, which currently includes 26 commodities.

Image: Australian government, under International Licence

CC BY 4.0

But how to actually bring critical mineral processing and manufacturing onshore?

The strategy notes independent modelling has found increasing exports of critical minerals and energy-transition minerals could create more than 115,000 new jobs and add $71.2 billion to Australia’s GDP by 2040.

“However, the number of jobs could increase by 262,600 and the increase in GDP strengthen to $133.5 billion by 2040 if Australia builds downstream refining and processing capability and secures a greater share of trade and investment,” it says.

Image: Anthony Albanese

Despite clearly flagging processing could almost double revenues, the strategy does not include a government support scheme to incentivise businesses to processes or build manufacturing capacity onshore.

Rather what it does is repeatedly hand off to other funds or initiatives like the Critical Minerals Development Program, Critical Minerals Facility, the Australian Made Battery Plan, which gives the sense of an endless merry-go-round.

The impetus to build sovereign processing and manufacturing capability does not stand alone in the strategy either, but is folded into one of the six focus areas, entitled ‘Developing strategically important projects, with targeted support.’

Exactly what form this ‘targeted’ support will take has some definition when it comes to mining exploration but very little for anything downstream of that. “The government is analysing the type and volumes of minerals our emerging downstream processing and manufacturing sectors will need and when they will need them and where the best economic gains are in the chain of production of batteries,” the Strategy says.

“This includes considering policy options that enable domestic supply of Australian critical minerals for Australian projects. The form and remit of any future approach must be tailored to the specific needs of the Australian economy within the global context.”

Like the federal government’s recent EV Strategy, this reads more like plan to make a plan, rather than an actual plan.

Somewhat alarmingly, the strategy also notes: “Foreign companies are securing ownership and offtake arrangements for a large share of Australian minerals, particularly lithium and rare earth elements. In this context, Australian processors and manufacturers may struggle to access supplies of Australian minerals in future. This would affect our strategic and energy security.”

The sole solution offered to this predicament is “encouraging collaboration with, and attracting investment from, global firms that have developed and proven their IP [intellectual property] overseas.” To that end, the government has allocated $57.1 million to secure strategic and commercial partnerships, but again does not include any guidance on what an attractive partnership might entail.

Keen eyes on ‘improving community sentiment’

The strategy’s other five focus areas include:

- Attracting investment and building international partnerships, to optimise trade and investment settings for priority technologies

- First Nations engagement and benefit sharing, to strengthen engagement and partnership with First Nations people and communities, and to improve equity and investment opportunities for First Nations interests

- Promoting Australia as a world leader in environmental and social governance (ESG) standards

- Unlocking investment in enabling infrastructure and services

- Growing a skilled workforce

The strategy is clearly aware of the past social and environmental misdeeds of Australia’s mining industries and the deep distrust these have rooted among communities, especially First Nations Australians. One of the key actions the strategy highlights is the need to work with state and territories to “improve community sentiment” on the mining industry.

Image: Mineral Resources Limited

The strategy talks at length about the need for better First Nations engagement, but again most of the key actions include developing frameworks which will fall under reforms to the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act), expected to happen this year.

While there has been much excitement about these reforms engendering a federal Environment Protection Agency or EPA, some have raised concerns that they place too much power in the hands of ministers, with little ability to challenge those decisions. Details on the reforms are still in the making.

It is worth noting here that Australia’s critical minerals will need to be virgin mined from now until the foreseeable future, and this process often involves clearing native forests. With much of this mining happening in Western Australia, news outlet WAToday recently noted that prospectors have sought exploration and mining permits across more than 1 million hectares of farm land and native forest in the southern half of the state in the six months from late 2022 to early 2023 alone.

This is to say, to reach this mineral superpower status, mining industries in Australia will grow considerably.

Meanwhile, a recent report from the Jubilee Australia Research Centre warned the race to capitalise on “staggering” material demand could see Australia dig up more critical minerals than necessary.

Image: Iluka Resources

The massive environmental impact from mining critical minerals is often overlooked by its primary customers: the renewable energy equipment industries. These impacts also extend to mineral processing – with Quinbrook Infrastructure Partners co-founder and Managing Partner, David Scaysbrook, last year raising the question of whether Australia actually has the stomach to become a critical minerals superpower.

“Onshore processing of critical minerals is fantastic from a job creation perspective, it’s fantastic from a value add economic stimulus point of view, but some of these processes do have significant environmental impacts,” Scaysbrook said at a briefing last November.

He added that countries like China are able to embrace “some of the more impactful processes” on the environment, processes which, historically, Australia has baulked at.

As it stands, these questions have barely made their way into Australia’s mainstream media, let alone national discussions. At some stage, the paradox of destroying forests to save the planet with decarbonisation technologies will almost undoubtedly appear.

The federal government is set to review its Critical Minerals Strategy in 2026.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.