From pv magazine 02/2022

In a cul-de-sac in the centre of Australia, 18 tin-roof houses rise out of red dirt. As many as 50 families live here in Marlinja, one of the Northern Territory’s most remote Indigenous communities. It is in their backyard the world’s largest solar project is to be built.

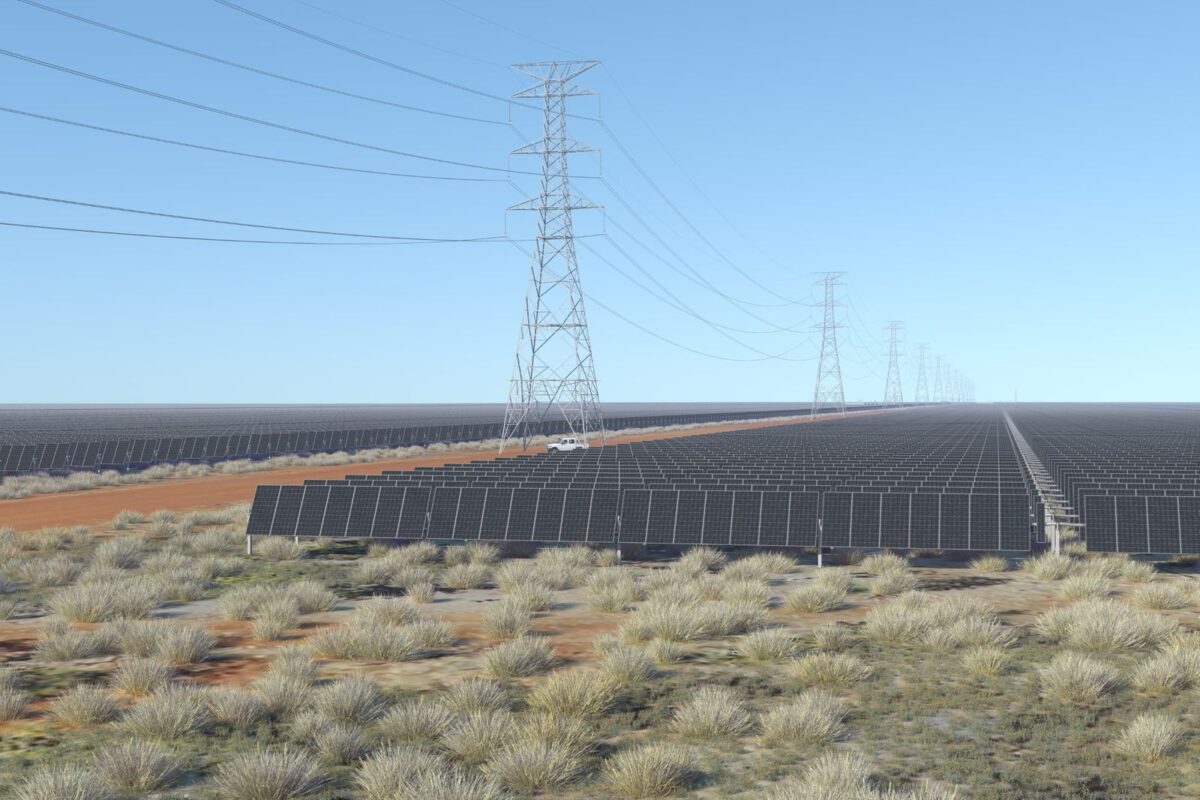

Sun Cable is striving to supply 15% of Singapore’s total power demand through undersea cables, with up to 20GW of solar supported by 42GWh of battery storage. And yet, the community soon to be living among these vast arrays currently doesn’t have the electricity required to keep their refrigerators running.

For First Nations Australians living on their ancestral lands, such situations are commonplace. Not only are the diesel gensets which power the communities unreliable and dirty, the electricity they produce is expensive – a fact which intermingles with regulations to routinely leave communities both literally and figuratively powerless. In the 2018-19 Australian financial year, 74% of households in the Northern Territory’s remote Indigenous communities lost power more than 10 times, mostly on “dangerously” hot days, a recent study published in Nature Energy found.

Original Power

“If that was Sydney or Melbourne, no one would put up with the power being out for even more than a minute, but because this is Aboriginal communities, the same reliability standards and expectations aren’t in place,” Luritja man Chris Croker tells pv magazine.

Solar developers are hardly the first big businesses to venture into Australia’s heart; mining and resource industries have been operating there for decades. Bearing witness to the export of these resources, which impoverished the land’s traditional owners while the nation grew rich, led Croker, one of Australia’s first Indigenous mining engineers, to co-found Impact Investment Partners – an infrastructure investment company funding renewable projects in Indigenous communities.

Far from a purely social venture to provide reliable, affordable power, Croker is convinced that First Nations participation can elevate clean energy projects, potentially even opening up vast new plains of opportunity for developers. If, that is, they are willing to listen.

Traditional practices

First Nations Australians lay claim to the longest continuous culture on earth, having inhabited Australia for at least 60,000 years. Their land management practices took on a new light following the 2020 Black Summer bushfires which reduced government-managed forests to charred stalks, while swathes of land where Indigenous groups were able to follow cultural burning practices remained virtually untouched.

“If we can embed some of those traditional practices in land management into the future of clean energy developments, that actually really helps Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders to protect the things they need to protect, but also may actually produce a better outcome for the renewable energy project as well,” Croker says. “Understanding that cultural historic story, which community groups know backwards, actually really brings a richer understanding of longer-term risk management.”

Figuring the land itself, referred to as “country,” as a beloved relative, an intricate knowledge of its diverse and delicate ecosystems, flora and fauna and climatic patterns is shared among Australia’s many First Nations cultures. “That’s difficult for a non-Indigenous person to believe and see the value of I guess, which is why the First Nations Clean Energy Network wants to get out there and pull the right parties together and say ‘look, there’s actually benefit in having [Indigenous] community representation at the table.’”

Image: Chris Croker

The network Croker is talking about launched in November 2021 and seeks to enable First Nations communities to “share in the benefits of this clean energy revolution,” as Croker puts it.

More than 60% of Australia’s landmass is held in Indigenous Estate, meaning First Nations groups either hold native title or other land right claims. Although Australia’s Native Title Act is federal law, meaning it applies across the country, states and territories have retained sovereign rights over land, water and resources which leads to considerable variations in how the law is enacted. In Croker’s experience, navigating this is difficult for international renewable developers, which usually prefer to give Native Title-claimed land a wide berth.

Complex as it might be, Croker believes it would be more constructive for developers to form good working relationships with First Nations Australians rather than squabble over small subsets of unclaimed land. “If we work positively with Indigenous landowners and cultural groups we will actually enable many, many more opportunities,” he says.

Strong agreements

For these opportunities to be realised, strong agreements between developers and First Nations groups are imperative. In May 2020, mining company Rio Tinto destroyed sacred rock caves containing artefacts dating back 46,000 years, some of the oldest ever found in Western Australia. Among them, a braid comprised of several individuals’ hair, through which DNA could be traced linking the ancient inhabitants with today’s traditional owners, the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura people.

While heinous, the destruction of Juukan Gorge was neither illegal nor unique, though it illuminated how companies have sidelined traditional owners by negotiating them into weak agreements which ultimately give the companies final say, silencing First Nations protest through gag clauses. “It’s a completely unlevel playing field,” Australian National University researcher Lily O’Neill tells pv magazine, akin to sending regular citizens into the room to negotiate with highly priced teams of lawyers and consultants.

Image: Tony McAvoy

While First Nations Australians were theoretically afforded some control over their ancestral lands with the Native Title Act in 1992, the promise remains something of a mirage. “Native title rights are filled with potential power. The difficulty is that most [First] Nations [groups], to my observation, are having difficulty converting that potential into actual power,” says Wirdi man and barrister Tony McAvoy. McAvoy says it’s the absence of revenue and resources that prevents First Nations Australians from realising their rights.

“We’ve come from a place where only in my father’s generation we weren’t treated as humans, didn’t get a full education. Still there is desperate poverty in these communities where a lot of these projects are going to be,” explains Torres Strait Islander man Thomas Mayor. Mayor is the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Coordinator for the Maritime Union of Australia and there he’s witnessed many companies – especially in the mining and resource sector – make big promises to Indigenous groups, only to abandon them at a later stage.

“One of the reasons the [First Nations Clean Energy] network is so important and why building all this is so important is because it’s my understanding that it will be the same companies that profited from fossil fuels which will end up owning these [renewable projects], because they’ve got the money to invest,” Mayor says. “Unless power is given to First Nations to be able to be at the table as equals, then those benefits won’t go to where they should be, which is to those owners of the land that have been so terribly dispossessed and harmed, treated poorly in this country.”

Image: Thomas Mayor

Need for accountability

Mayor says environmental, social and governance (ESG) reporting is crucial for forcing ethical behaviour from companies. The destruction of Juukan Gorge was legal, but it cost the Rio Tinto CEO his job and prompted a mass divestment from fossil fuel extraction companies in Australia led by superannuation and other powerful investment funds.

“Superfunds are paying a lot of attention to this issue at the moment,” O’Neill says. She recently authored a report on how clean energy companies can build better agreements with First Nations communities, learning from the errors of the mining and resources sector.

O’Neill believes renewable projects are much more likely to find backing from big, institutional investors in Australia if they negotiate fairly with traditional owners. “For too long, native title holders have been seen as these adversaries, and they’re not … they’re key stakeholders,” O’Neill says. “In this day and age, particularly after Juukan Gorge, why would you risk negotiating a poor agreement when, by any cost–benefit analysis, it’s just not worth it for you as a company.”

Future hope

If divestment and court cases form the stick in the case for First Nations inclusion, the development of local workforces is the carrot.

In Borroloola, a town of about 800 near the Northern Territory’s coast, Croker’s Impact Investment Partners has been working with community-focused organisation Original Power since 2019 to plan a solar microgrid. Borroloola local resident and traditional owner Conrad Rory, who helps lead the work, is eager to see both the clean energy jobs and the morale they carry brought to fruition by the project.

“It gives us something to look forward to, something to look after,” Rory tells pv magazine. “Helps create something that’s theirs.”

Image: Original Power

Back in Marlinja, Original Power recently fitted the community centre with solar and hopes to connect all the community’s 18 houses to a 100kW ground mounted solar array by April. It’s successfully convinced Australian company 5B, known for its rapid-deployment mounting structures, to partner on the project. 5B is hoping to be part of the massive Sun Cable project in the community’s backyard, so building a project in Marlinja, Original Power posited, could provide an opportunity to train a local workforce.

“If we tackle the community need first, we can actually build a much stronger relationship there that would demonstrate the value of what you’re trying to build,” says Lauren Mellor, Coordinator of the Clean Energy Communities Project with Original Power said. “And you could actually build a system,” she adds, referring to the opportunity to train locals through the project.

Like Rory, Mudburra man and Marlinja community leader Ray Dixon is excited. When he talks about the plan to transition his town to solar, he speaks with laughter like joy rising out of him. “I can’t wait, man,” says Dixon. “It will be something amazing for us, for the community, for the future.”

More than panels

Yet to reap the full benefits of Indigenous participation, Djrau woman and director of Alinga Energy Consulting, Ruby Heard, says renewable industries must expand their definitions of sustainability.

Sustainability is about more than just putting down solar panels, says Heard, who is an electrical engineer. While renewable technologies better align with Indigenous practices of harnessing natural resources, living non-destructively and ultimately caring for the natural world, the industry still tends to view the planet as a resource rather than a source, she says.

“We’re barreling down this road where we go ‘[renewable energy] is hot right now, let’s just take as much of it as possible’ … and it’s just the wrong mindset to go into this with,” Heard says. “It’s important to recognise we cannot recreate these ecosystems nature has made.”

Like Heard, Croker sees First Nations inclusion as crucial to ensure Australia’s remarkable landscapes are preserved. His company is currently developing a project on land that is home to a patch of rare, slow growing Mulga trees and desert oaks.

“It may save $1,000 [to clear the trees] to run panels in a straight line, but the benefit of actually having that tree there to the local birds, and culture and people actually far outweighs cost of modifying the project boundaries and exclusion zones,” Croker says. “It’s not so much using new technology to be less destructive, but it’s actually using what we have in a less destructive way.”

For Heard, stories like these encapsulate the importance of Indigenous inclusion. “We will be the ones to act as we have done for thousands of years and be the custodians of the land.”

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

2 comments

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.