In its latest Australian National Outlook, released today, Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) projects that by 2060, despite Australia’s population having grown by 60%, our total primary energy use may rise by just 6% from today’s consumption levels; and the percentage of total energy coming from renewable sources may have increased from the current 3% to 37%, helping us achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions alongside a tripling of GDP.

That’s in the scenario dubbed Outlook Vision, selected as a positive and achievable outcome among many possible projections. A contrasting yet equally possible scenario, said James Deverell, Director of CSIRO Futures, in a preview of the new and exhaustively modelled ANO 2019 is known as “Slow Decline”.

In this less inspiring projection Australia is “only able to hit Paris 2030 targets by purchasing international permits and emissions stagnate beyond 2030”, Deverell told a small number of journalists at the Australian National Outlook (ANO) briefing yesterday.

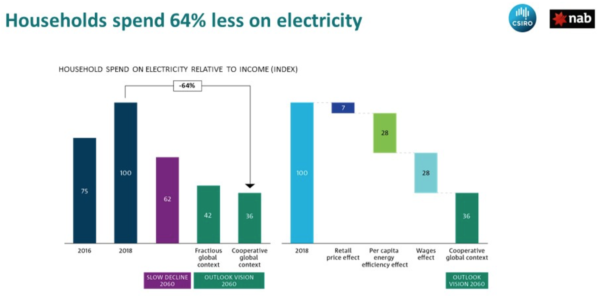

In the Outlook Vision scenario, Australian households could be spending 64% less on electricity as a percentage of their income than they do today, brought about by vastly improved energy efficiencies and a 90% increase in wages driven by the surge in GDP.

Increased population density in major cities will bring more people closer to where they live, work and play. Although electric vehicles will make up around 80% of new vehicle sales — because they’ll be 70% cheaper to run than conventional petrol-fuelled cars — the population’s proximity to essential elements of life, and government facilitation of effective ride-sharing and mass-transit systems will contribute to a 45% reduction in passenger vehicle use per capita, contributing significantly to reduced emissions from the transport sector.

“By contrast, in the Slow Decline projection,” says Deverell, “our major cities would continue to expand outwards, with little change in density, exacerbating congestion and leaving people on the urban fringe locked out of high-quality jobs and education.”

Achieving the most desirable outlook is predicated on Australia addressing a number of challenges, including disruptive technologies such as AI and genomics; a population both increasing and growing older; a decline in social cohesion caused by stagnant growth in real wages, issues of housing affordability and perceived generational inequality; a decline in trust in our institutions; and climate change.

“If we fail to tackle the economic, environmental and social challenges,” says Deverell, “we may face a low decline.”

CSIRO has been working on its second ANO for two years. The first was published in 2015, with a view to 2050. In the introduction to that groundbreaking analysis, Chief Executive of CSIRO, Dr Larry Marshall wrote that it was focused “on the emerging water-energy-food nexus, and the prospects for Australia’s energy, agriculture and other material intensive industries in the context of multiple uncertainties and opportunities”.

This new ANO was formulated with the input of 50 senior leaders from a diverse range of Australian organisations, such as National Australia Bank, the Australian Stock Exchange, Lend Lease and Shell; community groups and NGOs such as the Australian Red Cross and Uniting Care; and three of Australia’s most prestigious universities.

“We asked them what they thought would be important to create a better future for Australia,” says Deverell, a process conducted over eight workshops, several of more than a day’s duration. The results he says were then integrated with, “the best available science data and modelling from CSIRO, to project economic, environmental and social outcomes for Australia across multiple scenarios looking out to 2060”.

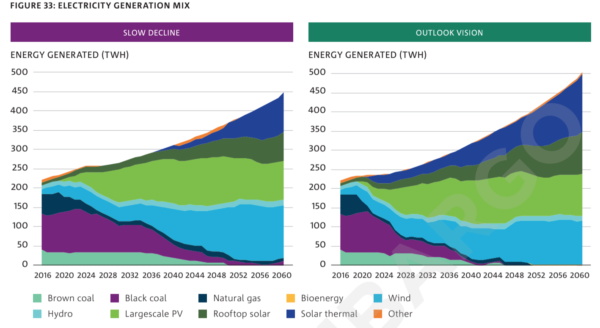

One factor that defied the projections of the 2015 Outlook, says Deverell, is the rapid decline in the cost of solar and wind generation. Electricity supply will be 100% renewable under either the Vision Outlook or Slow Decline scenario. He adds, that with the cost of battery storage following a similar trajectory, “our modelling shows that in the long run, renewables backed by storage become the low-cost solution, and market forces will push us in that direction.”

Graph: CSIRO

Nonetheless, CSIRO notes the need to “manage” this transition to a renewable-energy-fed grid — as the first prosperity-driving shift required by Australia’s energy landscape.

The second is, “To improve energy productivity using available technologies to reduce household and industrial energy use.” Says Deverell, “We can triple energy productivity … so we use less energy per unit of GDP.”

And the third strategy supported by modelling outlined in ANO 2019 is to use Australia’s abundant solar and wind resources to, “Develop new low-emissions energy exports, such as hydrogen and high-voltage direct-current power.” In 2018, CSIRO published a National Hydrogen Roadmap for Australia, leading Deverell to confidently predict, “We could turn our vast renewable resources into an economic opportunity, creating new sources of growth and jobs, and helping countries like Japan and Korea to reduce their emissions.”

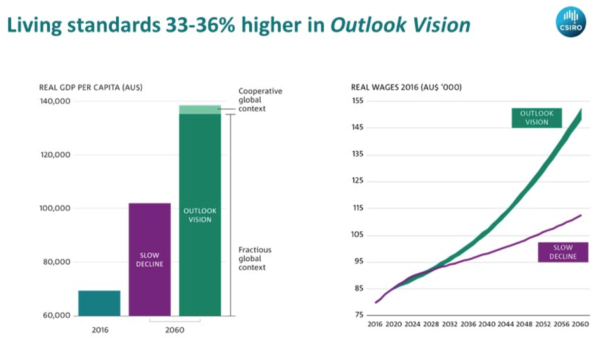

According to the Australian National Outlook, industry, urban planning and land use each requires three changes in approach to contribute to a 2060 in which Australia’s living standards could be as much as 36% better than under the Slow Decline projection, not just in terms of GDP, but on indices such as social inclusion and equality of opportunity.

The biggest challenge says Deverell may well be in turning around Australia’s cultural landscape, since each of the other areas identified for reshaping “will require a long-term view and bold concerted action to achieve the underpinning levers”. The cultural barrier is that “the very institutions that we would rely on for this leadership have lost public trust”, without which they lack the agency to act.

Deverell proposes that maybe Australian institutions should view agency in another way. He says it could be that, “The only way our government and companies can regain the public’s trust is by showing long-term commitment to the long-term interests of the country.”

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.