Deakin researchers have developed a first-of-its-kind lithium metal battery prototype using specially-designed electrolytes resistant to catching fire. The breakthrough from Deakin’s Institute for Frontier Materials (IFM) is said to represent a viable alternative to rechargeable lithium-ion batteries currently in use in portable electronics, stationary energy storage, and electric vehicles and is the culmination of more than 10 years of work by IFM electromaterials experts.

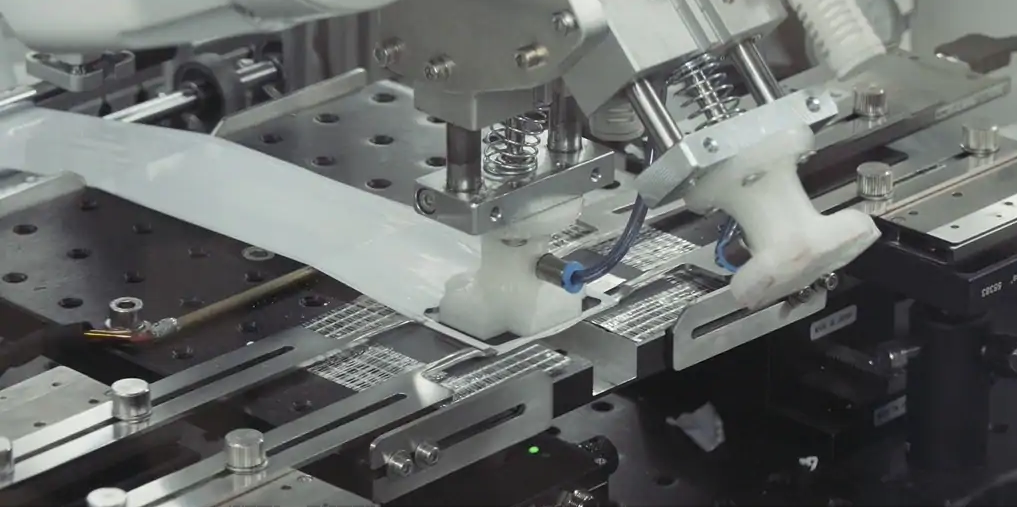

A new 1Ah (one amp-hour) sized lithium metal pouch cell was the first such battery Deakin had created using ionic liquid electrolytes, which according to Professor Patrick Howlett, Director of the University’s Battery Technology Research and Innovation Hub (BatTRI-Hub), allows for good safety, high temperature stability, and high voltage stability for increased energy storage capacity.

The new class of electrolyte material called an ionic liquid is a salt that takes on a liquid form at room temperature. Over the past 30 years, researchers at Deakin and Monash University have been working on these materials, which have begun to attract widespread interest in the battery community, due to their unique properties.

“Ionic liquids are non-volatile and resistant to catching fire, meaning that unlike the electrolytes currently used in lithium-ion cells used by, for example Samsung and Tesla, they won’t explode,” Professor Howlett explains. “Not only that, but they actually perform better when they heat up, so there’s no need for expensive and cumbersome cooling systems to stop the batteries from overheating.”

Changing features

On top of those benefits, the aspect of ionic liquid electrolytes that has most inspired the team’s research efforts is their outstanding ability to cycle energy-dense lithium metal electrodes. IFM Research Fellow Dr Robert Kerr, who has worked on translating these materials into real devices, says that by changing the materials that go into the batteries, we can change a number of key features.

“For example, if we change the electrodes to include lithium metal we can increase the storage capacity for up to 50% longer run-times. When we change the electrolyte, it can give a higher discharge rate or allow the battery to operate at much higher temperatures – but the electrolyte must be compatible when in contact with the reactive lithium metal electrode,” Kerr said. “By choosing the right electrolyte chemistry we can completely avoid the catastrophic explosions caused by ignition of the volatile electrolyte when the cell is damaged or overcharged.”

While lithium metal batteries could offer far better energy density and much lower weight than current lithium-ion technology as they replace heavier graphite with lithium metal as the anode material, lithium metals do not work well with conventional electrolytes. Another headwind for this innovative technology is that there is little knowledge about the best way to manufacture these cells at practical levels for demonstration given that the use of lithium metal electrodes in lithium metal batteries is not common in the battery industry. Therefore, the breakthrough, which is described as “just a stepping stone on the way to 1.7Ah cells, which are soon to be in production”, represents an important milestone in the battery world.

The project has been progressing at a rapid pace since the formation of the Deakin BatTRI-Hub in 2016. The potential of ionic liquid electrolytes is also being explored under a separate three-year project run by IFM and BatTRI-Hub in collaboration with CSIRO spin-off chemical manufacturer Boron Molecular and technology company Calix.

The project, which received $3 million from the Federal Government’s Cooperative Research Centre Projects (CRC-P) program last year, aims to develop high performance, low-cost, fast charge-discharge lithium-ion hybrid batteries based on nano-active electrode materials and ionic liquid electrolytes. It will explore the use of CalixFlash Calcination (CFC) technology to produce customized micron-sized nano-electroactive materials for intercalation-based anodes and cathodes. This would be integrated with optimized ionic electrolytes, developed with Boron Molecular and Deakin, to make up to 10 kWh battery pack prototypes at Deakin, through Bat-TRI-Hub.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

Keeping energy density up and bringing application costs down by getting rid of complex BMS, air conditioning, and fire suppression systems will bring down costs of large commercial energy storage systems below that magic $100/kWh of energy storage. Would companies entertain using the typical 300 to 400VDC solar PV string with a 300 to 400VDC battery pack to create the ability to change over grid tied solar PV to grid interactive Solar PV with the capability to add 100 to 200kWh of energy storage with smart ESS that could take care of the home’s electricity needs for (most) of the time? Bring it on!!