According to the Air Transport Action Group (ATAG) aviation is responsible for 12% of all CO2 emissions from transport sources. But while electric trains and trams are a proven quantity and electric vehicles (EVs) are gaining momentum in the road transport sector every day, clean aviation is still in its infancy.

However, a new report from Australia’s national science agency, CSIRO, and with technical input and funding from Boeing, shows that clean hydrogen could be introduced to commercial aviation within five years, an opportunity to reduce emissions significantly.

Clean aviation is up in the air

It is not a velleity that delays commercial aviation from a flightpath to reducing emissions, but a technical threshold. Unlike electric and other sorts of clean vehicles on road, rail, or sea, it is a far more complex task for an aircraft to cope with the added weight of the batteries required to power a commercial airline. Unlike a car, a plane is sensitive to the most delicate design adjustments.

Dr Dries Verstraete of the University of Sydney’s (USYD) School of Aerospace, Mechanical and Mechatronic Engineering notes that increasing the mass of a car by 35% requires 13-30% more energy use. But increasing the mass of a plane by the same proportion requires 35% more energy use, because energy use is directly proportional in aircraft.

However, that is only the beginning of the technological hindrances to electric aviation. The sheer distances aircraft cover simply demand more energy than land transport vehicles require, and, of course, there are no grids or charging stations in the sky, meaning an aircraft has to carry all its energy with it.

According to Verstraete, the best available lithium ion batteries today pack a punch of 200 watthours (Wh) per kilogram, that’s 60 times less than aircraft fuel. If we were to see a regional electric commuter aircraft service, not only would batteries have to up their game, but they would have to do so whilst finding a four- to tenfold reduction in weight. Verstraete notes that improvement in battery technology has been around 3-4% per year, doubling roughly ever two decades, and that based on a continuation of this trend the horizon on which a small electric commuter aircraft could be seen won’t be until 2050.

Bring on the hydrogen

So, it seems we don’t quite have the time to wait for electric aircraft. But as the CSIRO and Boeing show in this recent report, fuelling the aviation industry using hydrogen fuel may be a much faster way to emissions reduction.

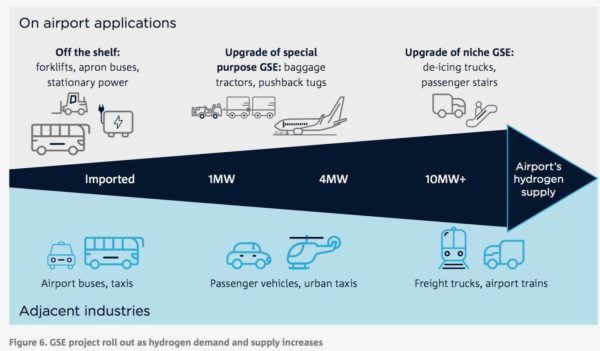

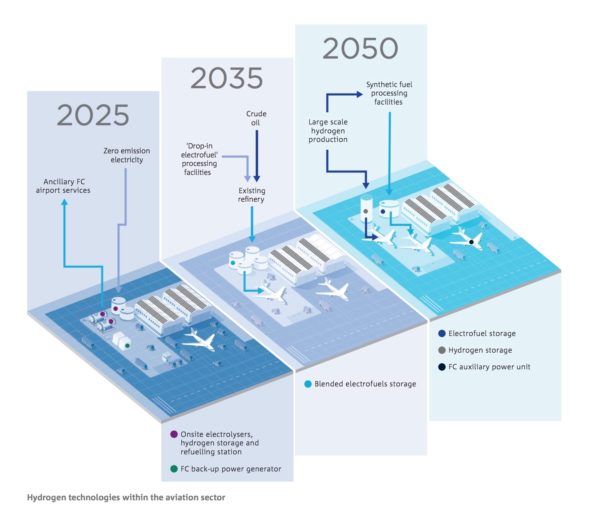

The report, ‘Opportunities for hydrogen in commercial aviation’, says that the acceleration of growth and technical facility in the clean hydrogen industry could see the clean fuel used for niche airport applications (ground support equipment and the like) by 2025.

Certainly, if we can’t clean up the skies straight away, we can at least get a good start on cleaning the world’s runways. In the long run however, the report says that due to the momentum of the hydrogen industry, a full transition from conventional jet fuel to hydrogen could take place between 2035-2050.

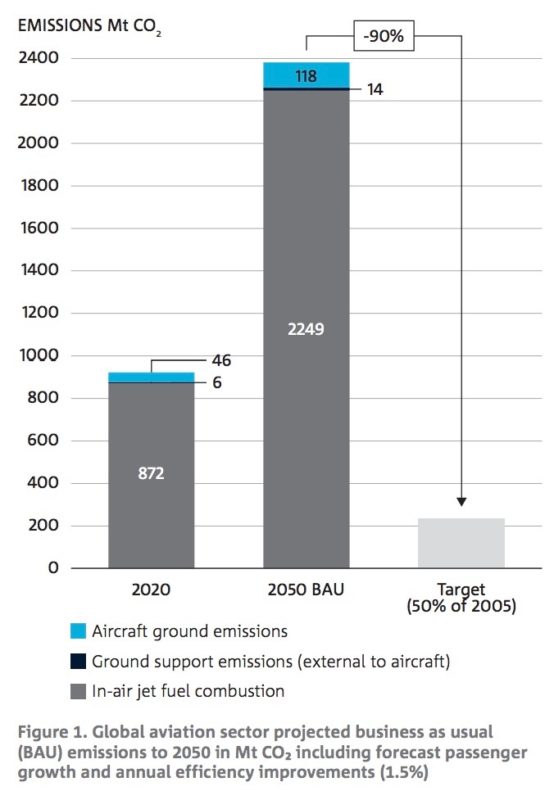

A study by the European Union found that a full transition to hydrogen fuel in the aviation industry would reduce the sector’s climatic impact by 75-90%. Bart Biebuyck, executive director of the Fuel Cells & Hydrogen 2 Joint Undertaking formed by the European Commission, Horizon 2020 and Hydrogen Europe, said that thanks to renewable energies the cost of producing hydrogen has dropped dramatically, and, at the same time, fuel cell performance has improved dramatically. “This combination has now made it possible to look to such solutions for decarbonisation of the aviation industry.”

CSIRO Chief Executive Dr Larry Marshall noted the interruption in the aviation industry’s normal service due to the Covid-19 pandemic has given the sector a chance to recognise its necessity to evolve with the clean energy transition.

“As we see travel resume,” said Marshall, “hydrogen presents a key solution to enable a sustainable recovery for the industry using liquid renewable fuel, and to grow future resilience from threats like oil shocks.”

Marshall went on to praise Boeing for its support of scientific progress and the determination to develop “a whole new sustainable and resilient industry that supports a green recovery.” That the hydrogen fuel in question is clean green hydrogen is important, especially considering Australia’s National Hydrogen Strategy remains “technology-neutral,” and the Morrison Government is keen to indulge the same cowardice in the prospect of a gas-fired recovery from the pandemic which, as Victoria well knows, is not through with us yet.

Boeing’s Australian General Manager of Research and Technology, Michael Edwards, said that Boeing and the sector are “committed to achieving the aviation industry goal of halving CO2 net emissions by 2050 relative to 2005 levels.”

“In addition to more efficient aircraft,” continued Edwards, “sustainable aviation fuels like hydrogen are a necessary contributor to the decarbonisation of aviation, and we are committed to furthering their development.”

Clean airports

If, as the poet W. H. Auden wrote, “every port has its name for the sea,” then every airport must also have its name for the sky, and for a growing number that name is “Solar.”

Many airports around the world, including Melbourne, Brisbane, and three Northern Territory airports, have already turned to solar PV. Indeed, Melbourne Airport is already constructing a solar farm in partnership with Beon Energy. Others, such as Sydney Airport, Adelaide Airport, and Gold Coast Airport, have turned to innovative funding mechanisms such as sustainability-linked loans which ties a borrower’s funding to its Environmental, Social and Governance rating or another such metric.

CSIRO’s report notes that solar PV and wind could provide ‘behind-the-meter’ solutions for hydrogen fuel technologies at airports in the future. “Within an airport boundary,” the report says, “there is typically considerable underutilised space that may be taken advantage of using solar PV.”

The report also quashed any fears that solar PV could be distracting for incoming pilots, noting that only a heliostat (mirror) used for concentrated solar thermal power would be a distraction, but that “traditional silicon panels primarily absorb rather than reflect light. There is already a precedent for solar farms at airports with Denver International Airport already hosting 2MW and currently implementing plans for expansion.”

Airlines are also beginning to take up some of the weight, something they are generally hesitant to do normally without charging heavy baggage fees. Late last year, Qantas was the first major airline to set itself a 2050 net-zero carbon emissions target, committing to cap its net emissions at 2020 levels.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

2 comments

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.